Herpaderping: Security Risk or Unintended Behavior?

The answer to that question often depends on who you ask.

By definition, process herpaderping is a hacking technique in which digital adversaries modify on-disk content after the image has been mapped in order to obscure the process. This obscurity can confuse security products or the operating system itself, sometimes allowing malicious code to be executed. For more information on process herpaderping, please read my earlier explainer post here.

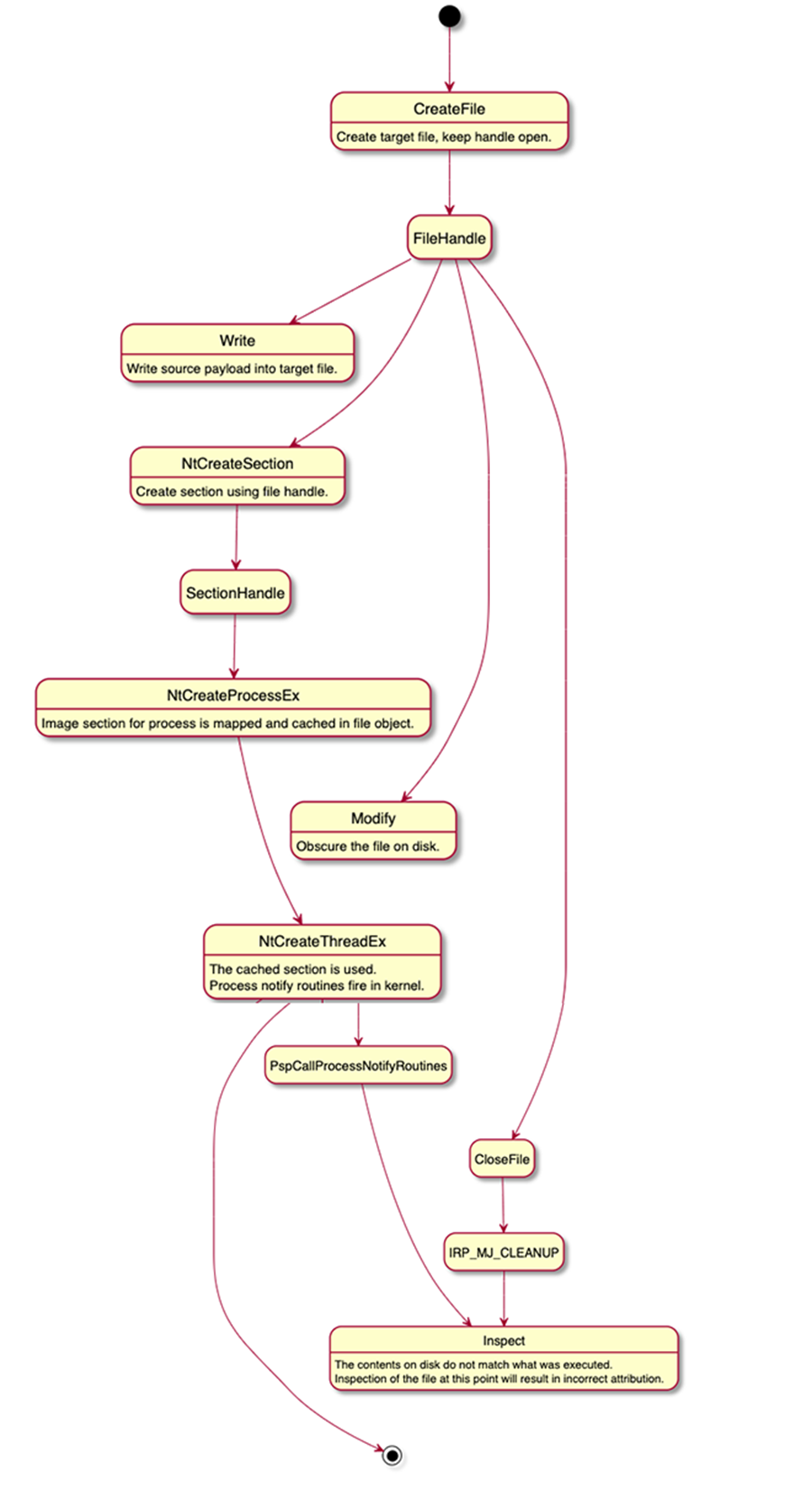

At a Glance: How Process Herpaderping Occurs

- Write target binary to disk, keeping the handle open. This is what will execute in memory.

- Map the file as an image section (NtCreateSection, SEC_IMAGE).

- Create the process object using the section handle (NtCreateProcessEx).

- Using the same target file handle, obscure the file on disk.

- Create the initial thread in the process (NtCreateThreadEx). At this point the process creation callback in the kernel will fire. The contents on disk do not match what was mapped. Inspection of the file at this point will result in incorrect attribution.

- Close the handle. IRP_MJ_CLEANUP will occur here. Since we’ve hidden the contents of what is executing, inspection at this point will result in incorrect attribution.

From an OS’s perspective, herpaderp attacks are often categorized as unintentional activity. But from a developer’s point of view, it’s a clear security threat—and a potent one at that.

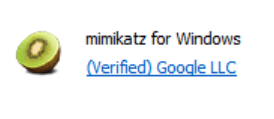

To illustrate this principle, let’s take a look at a recent example. Over the summer, it may have appeared that Google distributed a signed copy of Mimikatz. Sounds strange? It should because Google did not distribute a signed copy of Mimikatz. Rather, if you saw this, you were witnessing a case of process herpaderping, an exploit technique that obscures the intentions of a process by modifying the content on disk after the image has been mapped.

My team disclosed this process herpaderping attack to the Microsoft Security Response Center (MSRC) in mid-July. A case was opened a few days later. MSRC concluded their investigation near the end of August and determined the findings of the MSRC investigation were valid but did not require immediate servicing.

And with that, the case was closed—without a real resolution or timeline for future review, despite our reiterated belief to MSRC that this bug is severe.

What Does Herpaderping Mean for Developers?

The consensus from the cybersecurity community and researchers sees the situation quite differently. The POC shows this is exploitable and as a “defense evasion” or “masquerading” technique.

When an attack of this nature is miscategorized by an OS as unintentional activity it has major cybersecurity implications for any and all developers, not just security vendors. For example, where a Microsoft OS categorizes this attack as unintentional, Microsoft Defender Antivirus scans completed on the image backing the process may not prevent execution by a known malicious binary. Once the file is copied to the desktop, Microsoft Defender will likely realize there is a problem, but by then, the damage is done.

Many antivirus vendors are thought to be vulnerable to this type of attack, which means that many organizations are at risk of experiencing a herpaderping attack.

Herpaderping: How It’s Done

When the OS characterizes herpaderping as unintentional activity, it fails to address such exploits, and thus the burden of the solution falls on developers, both cybersecurity vendors and general app developers. But in order to defend against such attacks, we must first understand how they work.

Generally, a security product takes action on process creation by registering a callback in the OS kernel (PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutineEx). At this point, a security product may inspect the file that was used to map the executable and determine if this process should be allowed to execute. However, the kernel callback is invoked when the initial thread is inserted, not when the process object is created.

Because of this disconnect, an actor can create and map a process, modify the content of the file, then create the initial thread. A product that does inspection at the creation callback would then see the modified content.

In addition, some products use an on-write scanning approach that consists of monitoring for file writes. A familiar optimization is recording the file as written and deferring the actual inspection until IRP_MJ_CLEANUP occurs (e.g. the file handle is closed). Thus, an actor using a write -> map -> modify -> execute -> close workflow will subvert on-write scanning that solely relies on inspection at IRP_MJ_CLEANUP.

To abuse this convention, adversaries first write a binary to a target file on disk. Then, they map an image of the target file and provide it to the OS to use for process creation. The OS then maps the original binary. Using the existing file handle, and before creating the initial thread, the adversary then modifies the target file content to obscure or fake the file backing the image. Later, the initial thread is created in order to begin execution of the original binary. Finally, the target file handle can be closed.

Let’s look at an example of herpaderping in action.

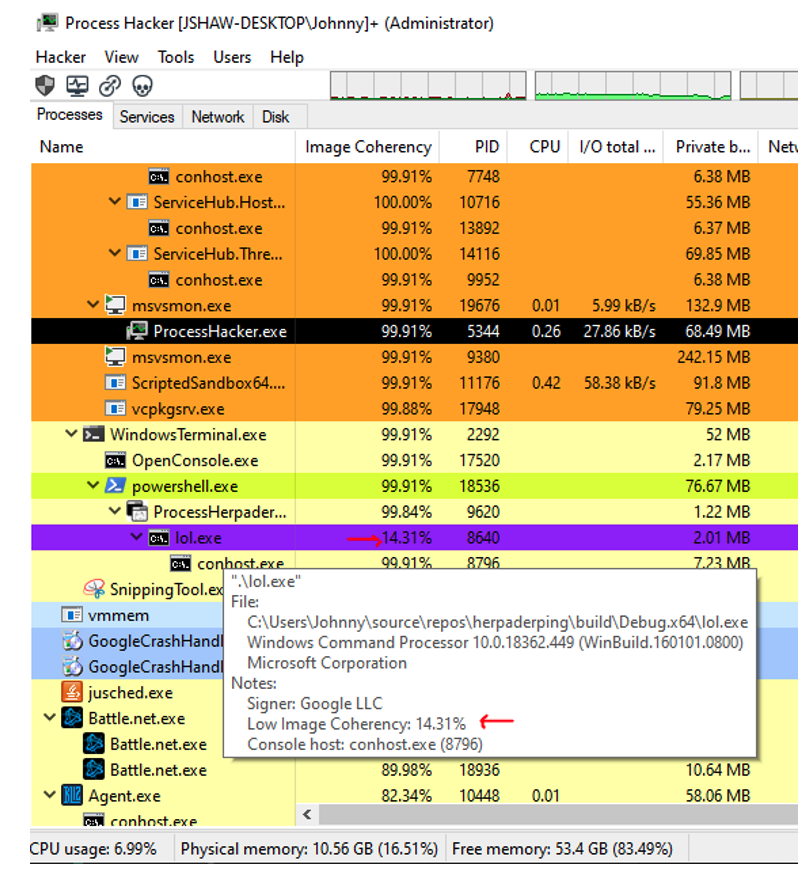

As you can see in the demo linked above, Cmd.exe is used as the execution target. The first run overwrites the bytes on disk with a pattern. The second run overwrites .exe with ProcessHacker.exe.

The herpaderping tool then fixes the binary to look as close to ProcessHacker.exe as possible, even retaining the original signature. Note the multiple executions of the same binary and how the process looks to the user compared to what is in the file on disk.

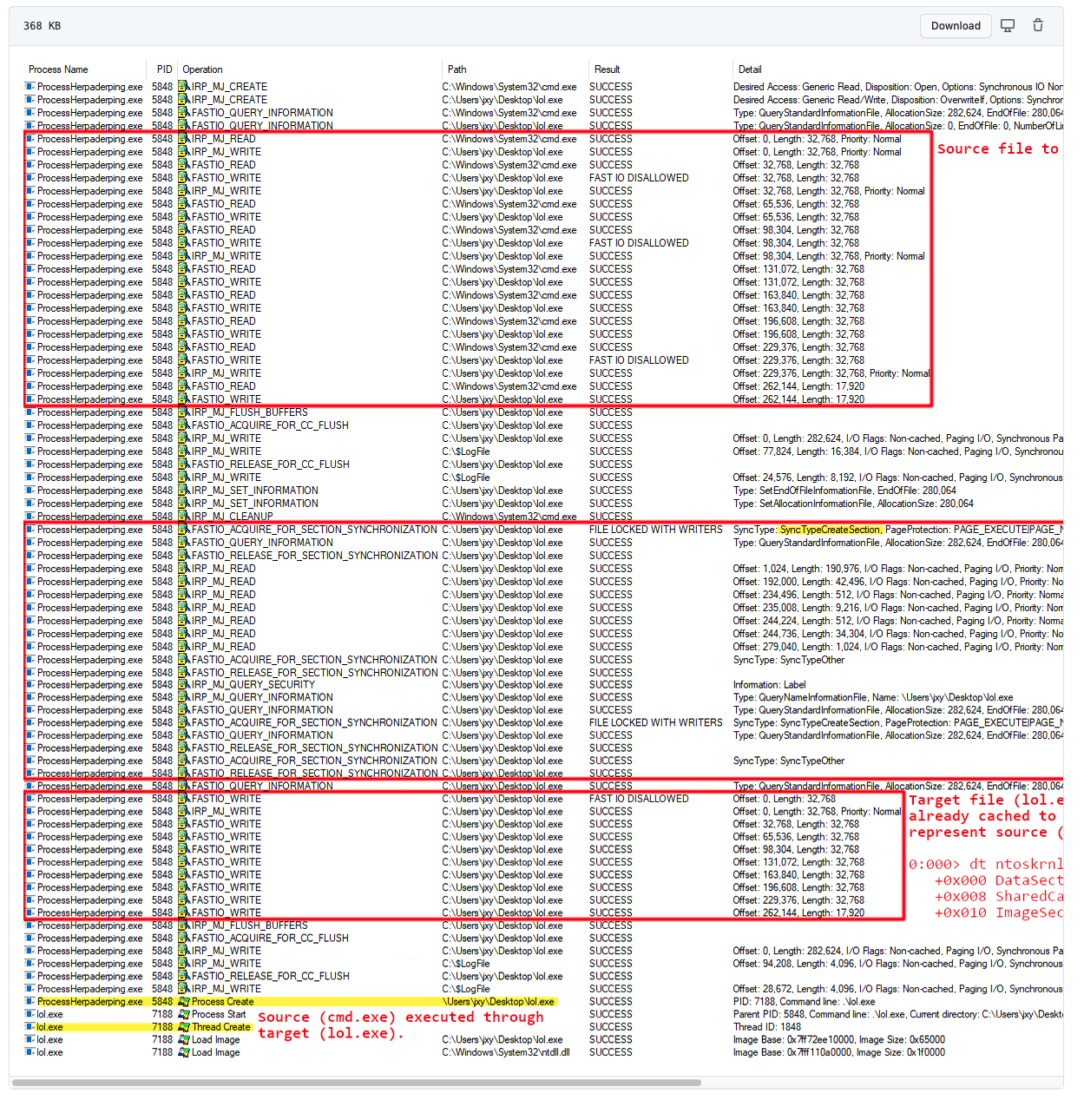

Looking at this flow from Process Monitor, we observe the source file being written and the OS mapping the image at the section creation. Using the same handle, the exploit overwrites the source binary with whatever it likes before creating the initial thread. By the time the process creation notification fires in the kernel the file backing the image is not what was mapped:

The SECTION_OBJECT_POINTERS of the FILE_OBJECT play a key role here. The OS will cache the initial image mapping and re-use the already mapped section, even if there is active write access to the FILE_OBJECT. This also means that a user can open the original file with exclusive access. While this won’t necessarily create an issue for the kernel callback, it does affect downstream logic in that it assumes that when the user opens the file with read access it will be broken. However, such logic does not apply, given that the file content has been overwritten. Further, the kernel callback is hopeless too, since reading directly from the file using that FILE_OBJECT will read the wrong data.

This also means if a user tries to execute that process again it will result in a sharing violation. From user mode, without access to that original target file handle, no one may conventionally execute the process.

Resolving This Issue: A Short-term Fix and Long-term Solution

Unfortunately, there is not a clear fix for herpaderping attacks. It seems reasonable that preventing an image section from being mapped/cached when there is write access to the file should close the hole. However, that may or may not be a practical solution.

There is a frustration among the development community about the incoherency between what is on disc and what it is going to execute, which is a common issue with all major operating systems. As such, that is something that should be considered when designing a security product.

While there isn’t a clear mechanism to guarantee that coherency, there are ways that security vendors, as well as security engineers and analysts, can foresee this issue and minimize the risk.

One way to detect this type of exploit is to look for write access to the related file object when the process is created. The exploit seems achievable through a higher-level API call. That said, the API juggling involved usually requires a native-call, which allows the attacker to tightly control the process creation flow.

Another way to detect this type of exploit is checking for coherency between the file on disk and the mapped process. Viewing the image coherency between the file on disk and the mapped process may be seen in an addition I’ve made to Process Hacker, and also shows the spoofed display of “Google” as the “signer” due to the exploit.

Here is a link to the enhancement proposal I’ve made to Process Hacker: https://github.com/processhacker/processhacker/issues/744

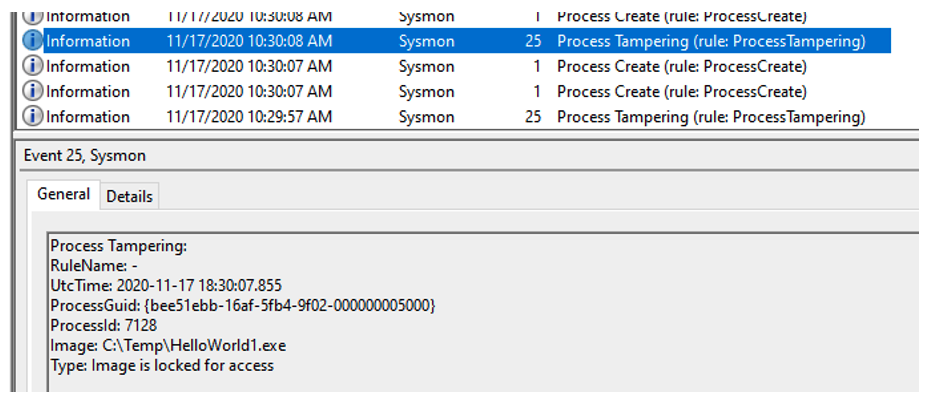

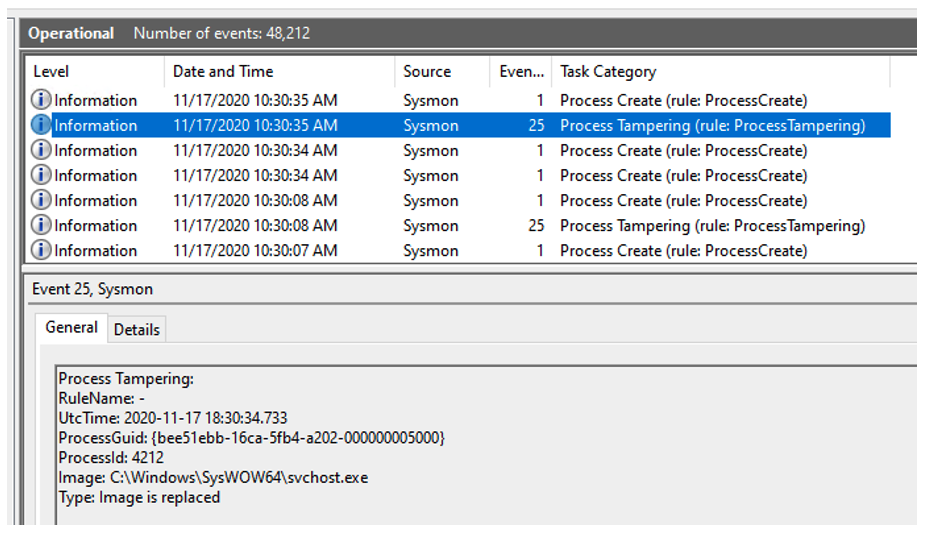

Process Tampering may also be seen through a recent addition to SysMon by Mark Russinovich, CTO of Microsoft Azure, reproduced below and in this tweet.

As for a long-term solution, that would require working with the OS to agree on a joint approach. We’re hopeful that as the technique gains broader awareness, the OS vendors will work with the cybersecurity community to adopt more stringent countermeasures directly in the OS.

What are your thoughts? How do you reduce the risk of herpaderping in the short-term? What steps do you think the OS community must take to address this issue more systematically? For additional context and insight, see what industry professionals are saying and join the conversation on Twitter.

https://twitter.com/gentilkiwi/status/1321001331755286529?s=20

https://twitter.com/Mordor_Project/status/1320949216018112514?s=20

https://twitter.com/jxy__s/status/1320873966752329729?s=20

https://twitter.com/analyzev/status/1320914701514084352?s=20

https://twitter.com/markrussinovich/status/1328769178233237504?s=20

Does this work sound interesting to you? Visit CrowdStrike’s Engineering and Technology page to learn more about our engineering team, our culture and current open positions: https://www.crowdstrike.com/careers/engineering-technology-team/