Early Bird Catches the Wormhole: Observations from the StellarParticle Campaign

StellarParticle, an adversary campaign associated with COZY BEAR, was active throughout 2021 leveraging novel tactics and techniques in supply chain attacks observed by CrowdStrike incident responders

- StellarParticle is a campaign tracked by CrowdStrike as related to the SUNSPOT implant from the SolarWinds intrusion in December 2020 and associated with COZY BEAR (aka APT29, “The Dukes”).

- The StellarParticle campaign has continued against multiple organizations, with COZY BEAR using novel tools and techniques to complete their objectives, as identified by CrowdStrike incident responders and the CrowdStrike Intelligence team.

- Browser cookie theft and Microsoft Service Principal manipulation are two of the novel techniques and tools leveraged in the StellarParticle campaign and are discussed in this blog.

- Two sophisticated malware families were placed on victim systems in mid-2019: a Linux variant of GoldMax and a new implant dubbed TrailBlazer.

Supply chain compromises are an increasing threat that impacts a range of sectors, with threat actors leveraging access to support several motivations including financial gain (such as with the Kaseya ransomware attack) and espionage. Throughout 2020, an operation attributed to the Foreign Intelligence Service of the Russian Federation (SVR) by the U.S. government was conducted to gain access to the update mechanism of the SolarWinds IT management software and use it to broaden their intelligence collection capabilities. This activity is tracked by CrowdStrike as the StellarParticle campaign and is associated with the COZY BEAR adversary group.

This blog discusses the novel tactics and techniques leveraged in StellarParticle investigations conducted by CrowdStrike. These techniques include:

- Credential hopping for obscuring lateral movement

- Office 365 (O365) Service Principal and Application hijacking, impersonation and manipulation

- Stealing browser cookies for bypassing multifactor authentication

- Use of the TrailBlazer implant and the Linux variant of GoldMax malware

- Credential theft using Get-ADReplAccount

Credential Hopping

The majority of StellarParticle-related investigations conducted by CrowdStrike have started with the identification of adversary actions within a victim’s O365 environment. This has been advantageous to CrowdStrike incident responders in that, through investigating victim O365 environments, they could gain an accurate accounting of time, account and source IP address of adversary victimization of the O365 tenant. In multiple engagements, this led CrowdStrike incident responders to identify that the malicious authentications into victim O365 tenants had originated from within the victim’s own network.

Armed with this information, CrowdStrike investigators were able to identify from which systems in these internal networks the threat actor was making authentications to O365. These authentications would typically occur from servers in the environment, leading to natural investigative questions: Why would a user authenticate into O365 from a domain controller or other infrastructure server? What credentials were used as part of the session from which the O365 authentication occurred?

This led our responders to identify the occurrence of “credential hopping,” where the threat actor leveraged different credentials for each step while moving laterally through the victim’s network. While this particular technique is not necessarily unique to the StellarParticle campaign, it indicates a more advanced threat actor and may go unnoticed by a victim.

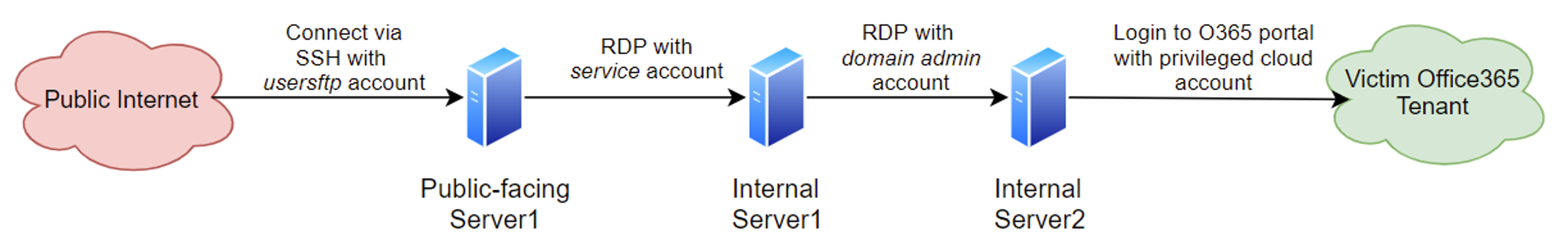

Below is an example of how a threat actor performs credential hopping:

- Gain access to the victim’s network by logging into a public-facing system via Secure Shell (SSH) using a local account <user sftp> acquired during previous credential theft activities.

- Use port forwarding capabilities built into SSH on the public-facing system to establish a Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) session to an internal server (Server 1) using a domain service account.

- From Server 1, establish another RDP session to a different internal server (Server 2) using a domain administrator’s account.

- Log in to O365 as a user with privileged access to cloud resources.

Figure 1. Example of “credential hopping” technique

This technique could be hard to identify in environments where defenders have little visibility into identity usage. In the example shown in Figure 1, the threat actor leveraged a service interactively, which should generate detections for defenders to investigate. However, the threat actor could have easily used a second domain administrator account or any other combination of accounts that would not be easily detected. A solution such as CrowdStrike Falcon® Identity Threat Detection would help identify these anomalous logons — and especially infrequent destinations for accounts. (Read how CrowdStrike incident responders leverage the module in investigations in this blog: Credentials, Authentications and Hygiene: Supercharging Incident Response with Falcon Identity Threat Detection.)

But how had the threat actor succeeded in authenticating into victim O365 tenants, when multifactor authentication (MFA) had been enabled for every O365 user account at each victim organization investigated by CrowdStrike?

Cookie Theft to Bypass MFA

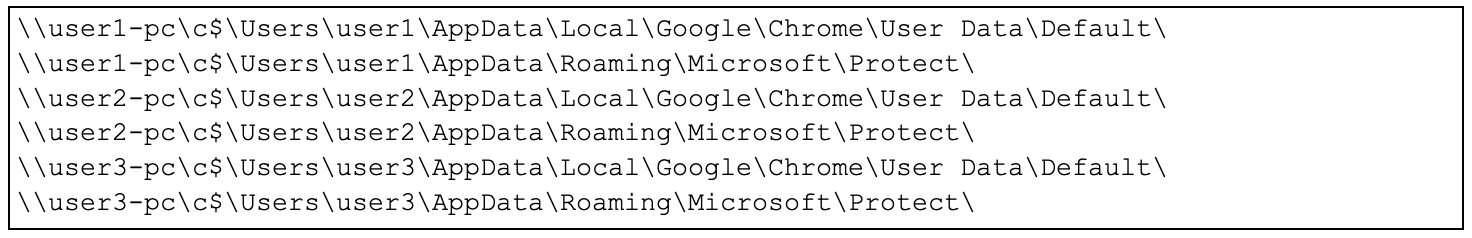

Even though the victims required MFA to access cloud resources from all locations, including on premises, the threat actor managed to bypass MFA through the theft of Chrome browser cookies. The threat actor accomplished this by using administrative accounts to connect via SMB to targeted users, and then copy their Chrome profile directories as well as data protection API (DPAPI) data. In Windows, Chrome cookies and saved passwords are encrypted using DPAPI. The user-specific encryption keys for DPAPI are stored under C:\Users\<user>\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Protect\. To leverage these encryption keys, the threat actor must first decrypt them, either by using the user account’s Windows password, or, in Active Directory environments, by using a DPAPI domain backup key that is stored on domain controllers.

Once the threat actor had a Chrome cookies file from a user that had already passed an MFA challenge recently (for example, a timeout was 24 hours), they decrypted the cookies file using the user’s DPAPI key. The cookies were then added to a new session using a “Cookie Editor” Chrome extension that the threat actor installed on victim systems and removed after using.

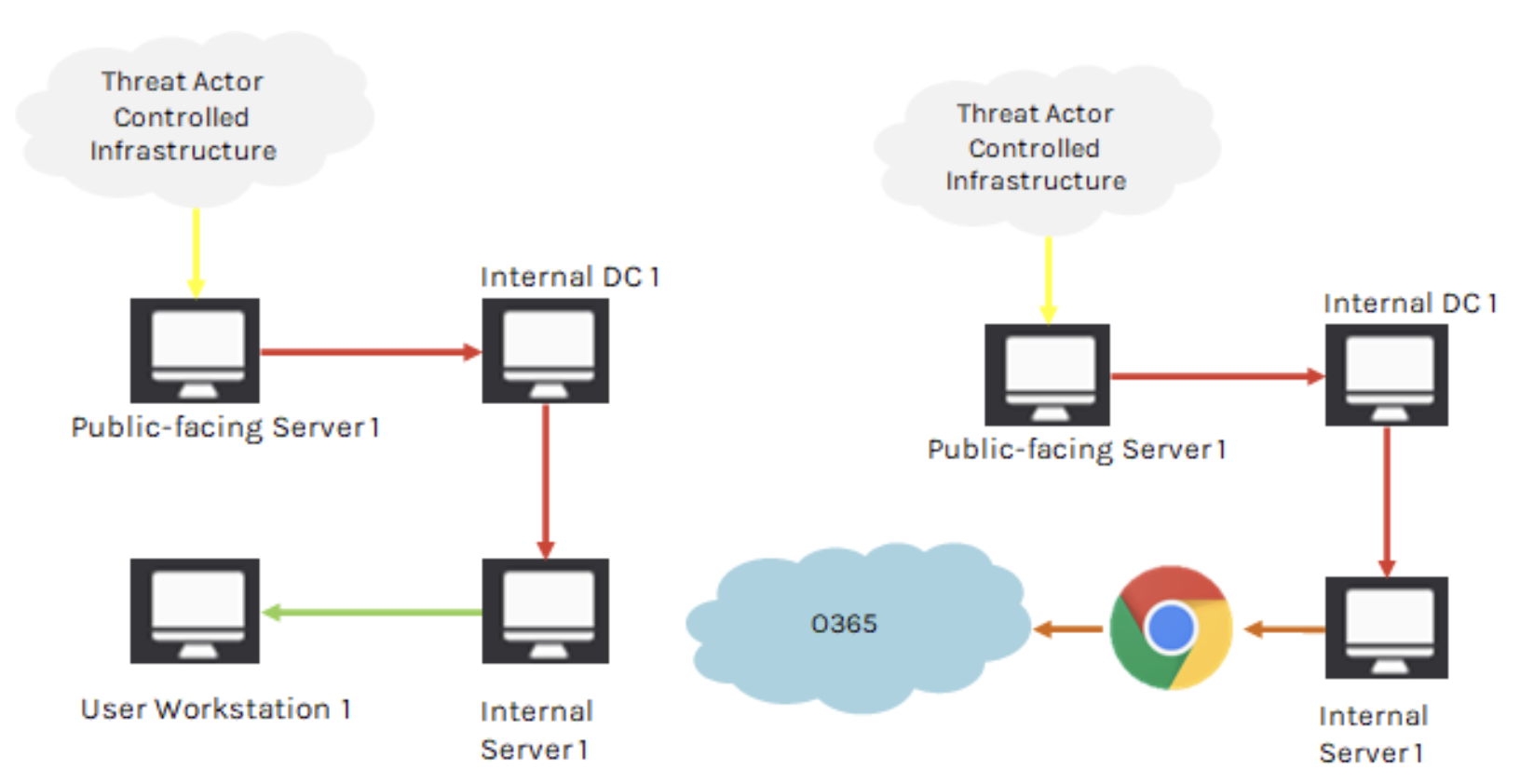

Shellbags, Falcon Telemetry and RDP Bitmap Cache

From a forensic standpoint, the use of the Cookie Editor Chrome extension would have been challenging to identify, due to the threat actor’s penchant for strict operational security. This activity was identified via a NewScriptWritten event within Falcon when a JavaScript file was written to disk by a threat actor-initiated Chrome process. This event captured the unique extension ID associated with the extension, thereby allowing CrowdStrike incident responders to validate via the Chrome Store that the JavaScript file was associated with the “Cookie Editor” plugin. This extension permitted bypassing MFA requirements, as the cookies, replayed through the Cookie Editor extension, allowed the threat actor to hijack the already MFA-approved session of a targeted user.

Shellbags were also instrumental in identifying the cookie theft activity. This artifact very clearly showed the threat actor accessing targeted users’ machines in sequence and browsing to the Chrome and DPAPI directories one after another. Parsing Shellbags for an administrative account leveraged by the threat actor resulted in entries similar to the below.

Figure 2. Shellbag artifacts showing targeting of Chrome directories

CrowdStrike identified forensic evidence that showed the entire attack path: browsing to a target user’s Chrome and DPAPI directories via administrative share, installing the Cookie Editor extension, and using Chrome to impersonate the targeted user in the victim’s cloud tenants. The decryption of the cookies is believed to have taken place offline after exfiltrating the data via the clipboard in the threat actor’s RDP session.

Figure 3. Representation of lateral movement to cookie theft to O365 authentication

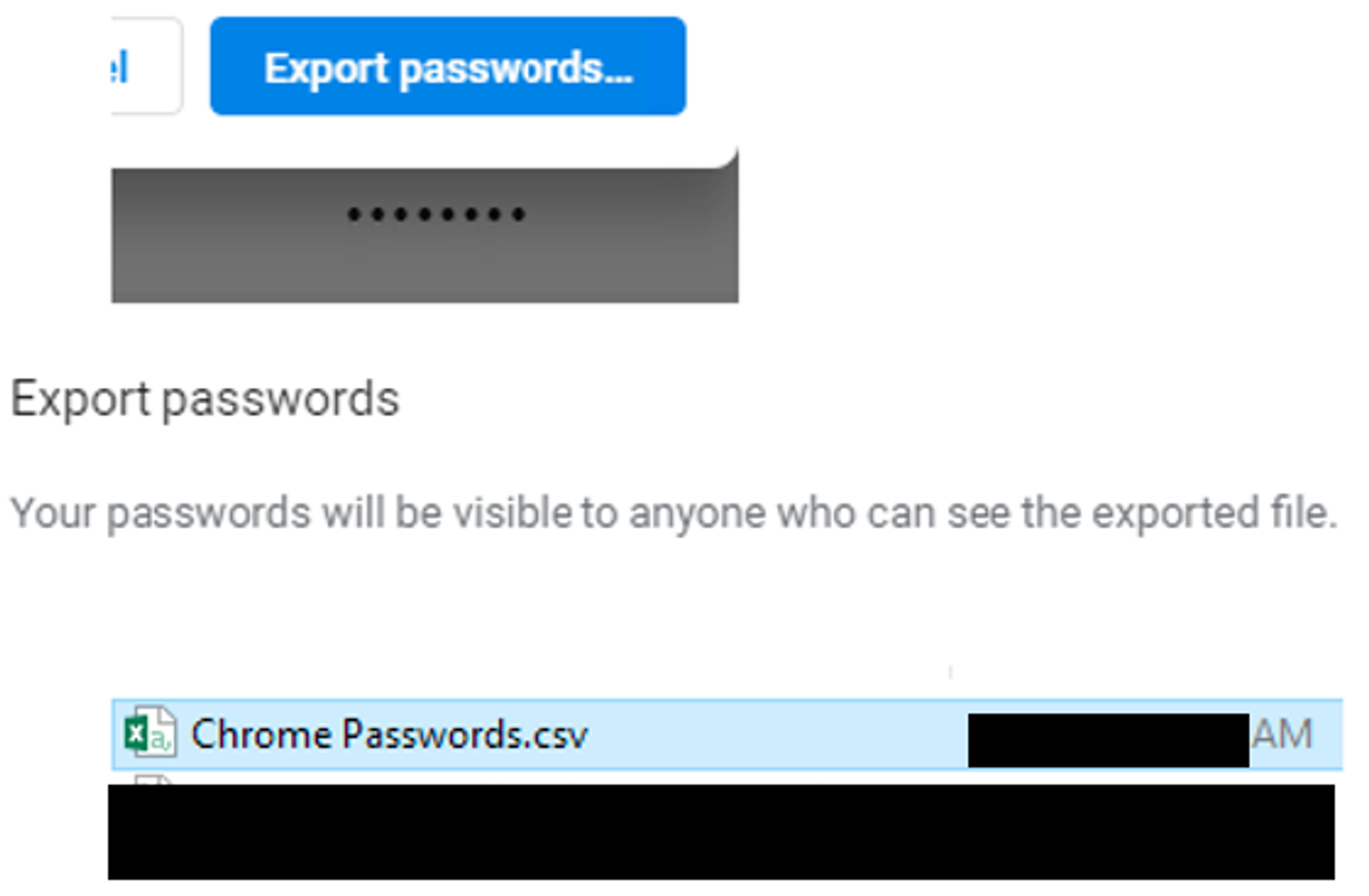

CrowdStrike identified a similar TTP where the threat actor connected via RDP to a user’s workstation with the workstation owner’s account (e.g., connecting via RDP to user1-pc using the account user1). In cases where the user had only locked their screen and not signed out, the threat actor was able to take over the user’s Windows session, as the RDP session would connect to the existing session of the same user. By examining RDP Bitmap Cache files, CrowdStrike was able to demonstrate that the threat actor had opened Chrome and exported all of the user’s saved passwords as plaintext in a CSV file during these sessions.

Figure 4. RDP Bitmap Cache reconstruction showing exportation of Chrome passwords

In addition, the threat actor visited sensitive websites that the user had access to, which in one instance allowed them to browse and download a victim’s customer list. After this, the threat actor navigated to the user’s Chrome history page and deleted the specific history items related to threat actor activity, leaving the rest of the user’s Chrome history intact.

O365 Delegated Administrator Abuse

CrowdStrike also identified a connection between StellarParticle-related campaigns and the abuse of Microsoft Cloud Solution Partners’ O365 tenants. This threat actor abused access to accounts in the Cloud Solution Partner’s environment with legitimate delegated administrative privileges to then gain access to several customers’ O365 environments.

By analyzing Azure AD sign-ins, CrowdStrike was able to use known indicators of compromise (IOCs) to identify several threat actor logins to customer environments. These cross-tenant sign-ins were identified by looking for values in the resourceTenantId attribute that did not match the Cloud Solution Partner’s own Azure tenant ID.

CrowdStrike also identified a limitation within Microsoft’s Delegated Administration capabilities for Microsoft Cloud Solution Partners. While a normal O365 administrator can be provided dozens of specific administrative roles to limit the privileges granted, this same degree of customization cannot be applied to Microsoft Cloud Solution Partners that use the delegated administrator functionality in O365.

For Microsoft Cloud Solution Partners, there are only two substantial administrative options today when managing a customer’s environment, Admin agent or Helpdesk agent.2 The Helpdesk agent role provides very limited access that is equivalent to a password admin role, whereas the Admin agent role provides broad access more equivalent to global administrator. This limitation is scheduled to be resolved in 2022 via Microsoft’s scheduled feature, Granular Delegated Admin Privileges (GDAP).3

User Access Logging (UAL)

The Windows User Access Logging (UAL) database is an extremely powerful artifact that has played an instrumental role in the investigation of StellarParticle-linked cases. In particular, UAL has helped our responders identify earlier malicious account usage that ultimately led to the identification of the aforementioned TrailBlazer implant and Linux version of the GoldMax variant.

The UAL database is available by default on Server editions of Windows starting with Server 2012. This database stores historical information on user access to various services (or in Windows parlance, Roles) on the server for up to three years (three years minus one day) by default. UAL contains information on the type of service accessed, the user that accessed the service and the source IP address from which the access occurred. One of the most useful roles recorded by UAL is the File Server role, which includes SMB access, though other role types can also be very helpful. An overview of UAL, what information it contains and how it can be leveraged in forensic investigations can be found here.

In multiple StellarParticle-related cases, because the threat actor used the same set of accounts during their operations in the environment, CrowdStrike was able to identify previous malicious activity going back multiple years, based solely on UAL data. Even though it’s only available on Server 2012 and up, UAL can still be used to trace evidence of threat actor activity on legacy systems as long as the activity on the legacy system involves some (deliberate or unintentional) access to a 2012+ system. For example, in addition to tracking SMB activity, UAL databases on Domain Controllers track Active Directory access.

This allowed CrowdStrike to demonstrate that a given user account was also authenticating to Active Directory from a given source IP address two years prior. Because the user account was known to have recently been abused by the threat actor, and the source IP of the system in question was not one that account would typically be active on, the investigation led to the source system and ultimately resulted in the timeline of malicious activity being pushed back by years, with additional compromised systems even being discovered still running unique malware from that time period.

TrailBlazer and GoldMax

Throughout StellarParticle-related investigations, CrowdStrike has identified two sophisticated malware families that were placed on victim systems in the mid-2019 timeframe: a Linux variant of GoldMax and a completely new family CrowdStrike refers to as TrailBlazer.

TrailBlazer

- Attempted to blend in with a file name that matched the system name it resided on

- Configured for WMI persistence (generally uncommon in 2019)

- Used likely compromised infrastructure for C2

- Masquerades its command-and-control (C2) traffic as legitimate Google Notifications HTTP requests

TrailBlazer is a sophisticated malware family that provides modular functionality and a very low prevalence. The malware shares high-level functionality with other malware families. In particular, the use of random identifier strings for C2 operations and result codes, and attempts to hide C2 communications in seemingly legitimate web traffic, were previously observed tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) in GoldMax and SUNBURST. TrailBlazer persists on a compromised host using WMI event subscriptions4 — a technique also used by SeaDuke — although this persistence mechanism is not exclusive to COZY BEAR.5

WMI event filter |

SELECT * FROM __InstanceModificationEvent WITHIN 60 WHERE TargetInstance ISA 'Win32_PerfFormattedData_PerfOS_System' AND TargetInstance.SystemUpTime >= 180 AND TargetInstance.SystemUpTime < 480 |

WMI Event consumer (CommandLineTemplate) |

C:\Program Files (x86)\Common Files\Adobe\<FILENAME>.exe |

Filter to consumer binding |

CommandLineEventConsumer.Name="<GUID1>"|__EventFilter.Name="<GUID2>" |

Table 1. TrailBlazer WMI Persistence

In the obfuscated example above, TrailBlazer (<FILENAME>.exe) would be executed when the system’s uptime was between 180 and 480 seconds.

GoldMax (Linux variant)

- Attempted to blend in with a file name that matched the system name it resided on

- Configured for persistence via a crontab entry with a

@rebootline - Used likely compromised infrastructure for C2

GoldMax was first observed during post-exploitation activity in the campaign leveraging the SolarWinds supply chain attacks. Previously identified samples of GoldMax were built for the Windows platform, with the earliest identified timestamp indicating a compilation in May 2020, but a recent CrowdStrike investigation discovered a GoldMax variant built for the Linux platform that the threat actor deployed in mid-2019. This variant extends the backdoor’s known history and shows that the threat actor has used the malware in post-exploitation activity targeting other platforms than Windows.

The 2019 Linux variant of the GoldMax backdoor is almost identical in functionality and implementation to the previously identified May 2020 Windows variant. The very few additions to the backdoor between 2019 and 2020 likely reflect its maturity and longstanding evasion of detections. It is likely GoldMax has been used as a long-term persistence backdoor during StellarParticle-related compromises, which would be consistent with the few changes made to the malware to modify existing functions or support additional functionality.

Persistence was established via a crontab entry for a non-root user. With the binary named to masquerade as a legitimate file on the system and placed in a hidden directory, a crontab entry was created with a @reboot line so the GoldMax binary would execute again upon system reboot. Additionally, the threat actor used the nohup command to ignore any hangup signals, and the process will continue to run even if the terminal session was terminated.

Figure 5. Crontab entry for GoldMax persistence

Enumeration Tools/Unique Directory Structure

Throughout our StellarParticle investigations, CrowdStrike identified what appeared to be a VBScript-based Active Directory enumeration toolkit. While the script’s contents have not been recovered to date, CrowdStrike has observed identical artifacts across multiple StellarParticle engagements that suggest the same or similar tool was used.

In each instance the tool was used, Shellbags data indicated that directories with random names of a consistent length were navigated to by the same user that ran the tool. After two levels of randomly named directories, Shellbags proved the existence of subdirectories named after the FQDNs for the victims’ various domains. In addition, the randomly named directories are typically created in a previously existing directory that’s one level off of the root of the C drive. The randomly named directories have a consistent length where the first directory is six characters and the next directory is three characters. To date, the names of the directories have always been formed from lowercase alphanumeric characters. For example, Shellbags indicated that directories matching the naming patterns below were browsed to (where “XX” is a previously existing directory on the system):

C:\XX\[a-z0-9]{6}C:\XX\[a-z0-9]{6}\[a-z0-9]{3}C:\XX\[a-z0-9]{6}\[a-z0-9]{3}\domain.FQDNC:\XX\[a-z0-9]{6}\[a-z0-9]{3}\domain-2.FQDN

In each case, immediately prior to the creation of the directories referenced above, there was evidence of execution of a VBScript file by the same user that browsed to the directories. This evidence typically came from a UserAssist entry for wscript.exe, as well as RecentApps entries for wscript.exe (that would also include the VBScript filename). In addition, the Jump List for wscript.exe contained evidence of the VBScript files. The name of the VBScript files varied across engagements and was generally designed to look fairly innocuous and blend in. Two examples are env.vbs and WinNet.vbs. Due to the subdirectories that are named after the FQDNs for victim domains, CrowdStrike assesses with moderate confidence that the scripts represent an AD enumeration tool used by the adversary.

Internal Wiki Access

Across multiple StellarParticle investigations, CrowdStrike identified unique reconnaissance activities performed by the threat actor: access of victims’ internal knowledge repositories.6 Wikis are commonly used across industries to facilitate knowledge sharing and as a source of reference for a variety of topics. While operating in the victim’s internal network, the threat actor accessed sensitive information specific to the products and services that the victim organization provided. This information included items such as product/service architecture and design documents, vulnerabilities and step-by-step instructions to perform various tasks. Additionally, the threat actor viewed pages related to internal business operations such as development schedules and points of contact. In some instances these points of contact were subsequently targeted for further data collection.

The threat actor’s wiki access could be considered an extension of “Credential Hopping” described earlier. The threat actor established RDP sessions to internal servers using privileged accounts and then accessed the wiki using a different set of credentials. CrowdStrike observed the threat actor accessing the wiki as users who would be considered “non-privileged” from an Active Directory perspective but had access to sensitive data specific to the victim’s products or services.

At this time, the malicious access of internal wikis is an information gathering technique that CrowdStrike has only observed in StellarParticle investigations. CrowdStrike was able to identify the wiki access primarily through forensic analysis of the internal systems used by the threat actor. Given the threat actor’s penchant for clearing browser data, organizations should not rely upon the availability of these artifacts for future investigations. CrowdStrike recommends the following best practices for internal information repositories:

- Enable detailed access logging

- Ensure logs are centralized and stored for at least 180 days

- Create detections for anomalous activity such as access from an unusual location like a server subnet

- Enable MFA on the repository site, or provide access via Single Sign On (SSO) behind MFA

O365 Built-in Service Principal Hijacking

The threat actor connected via Remote Desktop from a Domain Controller to a vCenter server and opened a PowerShell console, then used the PowerShell command -ep bypass to circumvent the execution policy. Using the Windows Azure Active Directory PowerShell Module, the threat actor connected to the victim’s O365 tenant and began performing enumeration queries. These queries were recorded in text-based logs that existed under the path

C:\Users\<user>\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Office365\Powershell\.

Similar logs (for Azure AD instead of O365) can be found under the path:

C:\Users\<user>\AppData\Local\Microsoft\AzureAD\Powershell\.

While the logs didn’t include what data was returned by the queries, they did provide some insight such as the user account used to connect to the victim’s O365 tenant (which was not the same as the user the threat actor used to RDP to the vCenter server). The logs contained commands issued and the count of the results returned for a specific command. The commands included enumeration queries such as:

ListAccountSkusListPartnerContractsListServicePrincipalsListServicePrincipalCredentialsListRolesListRoleMembersListUsersListDomainsGetRoleMemberGetPartnerInformationGetCompanyInformation

In this case, however, the most significant and concerning log entry was one that indicated the command AddServicePrincipalCredentials was executed. By taking the timestamp that the command was executed via the PowerShell logs on the local system, CrowdStrike analyzed the configuration settings in the victim’s O365 tenant and discovered that a new secret had been added to a built-in Microsoft Azure AD Enterprise Application, Microsoft StaffHub Service Principal, which had Application level permissions. Further, the newly added secret was set to remain valid for more than a decade. This data was acquired by exporting the secrets and certificates details for each Azure AD Enterprise Application.

The Service Principal (now renamed to Microsoft Teams Shifts) had the following permissions at the time the configuration settings were collected:

Member.ReadMember.Read.AllMember.ReadWriteMember.ReadWrite.AllShift.ReadShift.Read.AllShift.ReadWriteShift.ReadWrite.AllTeam.ReadTeam.Read.AllTeam.ReadWriteTeam.ReadWrite.AllUser.Read.AllUser.ReadWrite.AllWebHook.Read.AllWebHook.ReadWrite.All

CrowdStrike was unable to find Microsoft documentation, but based on open-source research,7 this application likely had the following permissions around the time of registration:

Mail.ReadGroup.Read.AllFiles.Read.AllGroup.ReadWrite.All

The most notable permissions above are the Mail.Read, Files.Read and Member.ReadWrite permissions. These permissions would allow the threat actor to use the Microsoft Staffhub service principal to read all mail and SharePoint/OneDrive files in the organization, as well as create new accounts and assign administrator privileges to any account in the organization.

By running the commands from within the victim’s environment, MFA requirements were bypassed due to conditional access policies not covering Service Principal sign-ins at this point of time.8 However, as explained earlier, the threat actor managed to continue to access the victim’s cloud environment even when the victim enforced MFA for all connections regardless of source.

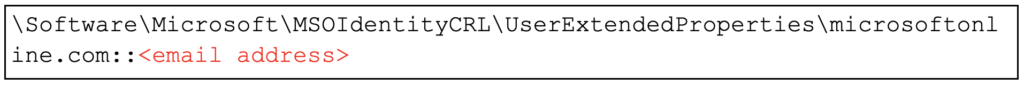

While the bulk of the evidence for this activity came from the text-based O365 PowerShell logs, the NTUSER.DAT registry hive for the user that was running the PowerShell cmdlets also included information on the accounts that were used to authenticate to the cloud. This information was stored under the registry path. Below is an example of the registry data:

Figure 6. Example registry entry showing target O365 email accounts

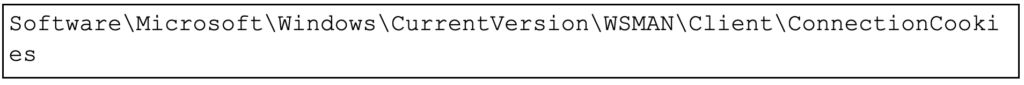

The same WSMan connection string was also located in the user’s NTUSER.DAT registry hive under the path:

Figure 7. WSMan connection string registry location

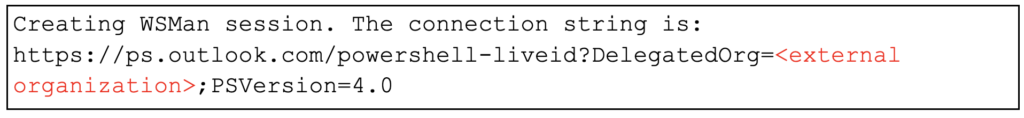

While not strictly related to the O365 PowerShell activity, the Windows Event Log Microsoft-Windows-WinRM%4Operational.evtx also included information on connection attempts made to external O365 tenants. This information was logged under Event ID 6. Below is an example of what the event included:

Figure 8. Windows Event Log entry showing connection to O365 tenants

O365 Company Service Principal Manipulation

The threat actor also deployed several layers of persistence utilizing both pre-existing and threat actor-created Service Principals with the ultimate goal of gaining global access to email.

Attacker-created Service Principal

First, the threat actor used a compromised O365 administrator account to create a new Service Principal with a generic name. This Service Principal was granted company administrator privileges. From there, the threat actor added a credential to this Service Principal so that they could access the Service Principal directly, without use of an O365 user account.

These actions were recorded in Unified Audit Logs with the following three operation names:

Add service principalAdd member to roleAdd service principal credentials.Update Service Principal

Company-Created Service Principal Hijacking

Next, the threat actor utilized the threat actor-created Service Principal to take control of a second Service Principal. This was done by adding credentials to this second Service Principal, which was legitimately created by the company. This now compromised company-created Service Principal had mail.read graph permissions consented on behalf of all users within the tenant.

This action was recorded by just one operation type in Unified Audit Logs. This operation type is named Add service principal credentials.

Mail.Read Service Principal Abuse

Finally, the threat actor utilized the compromised Service Principal with the assigned mail.read permissions to then read emails of several different users in the company’s environment.

CrowdStrike was able to use the Unified Audit Logs’ (UAL) MailItemsAccessed operation events to see the exact emails the threat actor viewed, as the majority of the users in the tenant were assigned O365 E5 licenses. When performing analysis on the UAL, CrowdStrike used the ClientAppId value within the MailItemsAccessed operation and cross-correlated with the Application ID of the compromised service principal to see what activities were performed by the threat actor.

O365 Application Impersonation

Another consistent TTP identified during StellarParticle investigations has been the abuse of the ApplicationImpersonation9 role. When this role was assigned to a particular user that was controlled by the threat actor, it allowed the threat actor to impersonate any user within the O365 environment. These impersonated events are not logged verbosely by the Unified Audit Logs and can be difficult to detect.

While the assignment of these ApplicationImpersonation roles were not logged in the Unified Audit Logs, CrowdStrike was able to identify this persistence mechanism via the management role configuration settings, which can be exported with the Exchange PowerShell command:

Get-ManagementRoleAssignment -Role ApplicationImpersonation.

CrowdStrike then analyzed the exported configuration settings and identified several users (not service accounts) that the threat actor likely gave direct ApplicationImpersonation roles during the known periods of compromise.

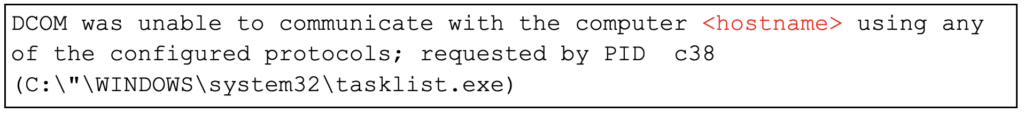

Remote Tasklist

The threat actor attempted to remotely list running processes on systems using tasklist.exe. As tasklist uses WMI “under the hood,” this activity was captured by Falcon as SuspiciousWmiQuery events that included the query and the source system. Additionally, the failed (not successful) process listing resulted in a DCOM error that was logged in the System.evtx event log under Event ID 10028. A sample of the information included with this event is below:

Figure 9. Event ID 10028 showing failed execution of remote tasklist

This remote process listing was consistently used by the threat actor targeting the same or similar lists of remote systems, and the owners of the targeted systems also happened to be the individuals with cloud access that the threat actor was interested in. While unproven, it’s possible the threat actor was running tasklist remotely on these systems specifically to see which of the target systems was running Google Chrome. This is because a current or recent Chrome session to the victim’s cloud tenants would be potentially beneficial in the hijacking of sessions that the threat actor performed in order to access the victim’s cloud resources.

FTP Scanning/Identity Knowledge

In one instance, after being evicted from a victim environment, the threat actor began probing external services as a means to regain access, initially focusing on (S)FTP servers that were internet-accessible. Logs on the servers indicated that the threat actor attempted to log in with multiple valid accounts and in several cases was successful. There was little to no activity during the (S)FTP sessions. This likely was an exercise in attempting to identify misconfigured (S)FTP accounts that also had shell access, similar to what’s described in the Credential Hopping section earlier. Some of the accounts used were not in the victim’s Active Directory, as these were accounts for customers of the victim and stored in a separate LDAP database. However, the threat actor had knowledge of these accounts and used them on the correct systems, which further confirmed that the threat actor had advanced knowledge of the victim’s environment.

After confirming the FTP accounts did not provide shell access into the environment, the threat actor began attempting to connect into the environment via VPN. The threat actor attempted to log in to the VPN using several user accounts but was prevented from connecting, either due to not having the correct password, or due to having the correct password but not getting past the recently implemented MFA requirement. Eventually, the threat actor attempted an account that they had the correct password for but that had not been set up with MFA. This resulted in a prompt being displayed to the threat actor that included an MFA setup link. The threat actor subsequently set up MFA for the account and successfully connected to the victim’s network via VPN.

TA Masquerading of System Names

During the attempted and successful VPN authentications described above, the threat actor ensured the hostname of their system matched the naming convention of hostnames in the victim’s environment. This again showed a strong knowledge of the victim’s internal environment on the part of the threat actor. Not only did the masqueraded hostnames follow the correct naming convention from a broad perspective, they were also valid in terms of what would be expected for the user account the threat actor leveraged (i.e., in terms of the site name and asset type indicated in the hostname). This masqueraded hostname technique has been observed at multiple StellarParticle-related investigations.

Credential Theft Using Get-ADReplAccount

In one example, the threat actor connected into the victim’s environment via a VPN endpoint that did not have MFA enabled. Once connected to the VPN, the threat actor connected via Remote Desktop to a Domain Controller and copied the DSInternals10 PowerShell module to the system. The threat actor subsequently ran the DSInternals command Get-ADReplAccount targeting two of the victim’s domains. This command uses the Microsoft Directory Replication Service (MS-DRSR) protocol and specifically the IDL_DRSGetNCChanges method to return account information from Active Directory such as the current NTLM password hashes and previous password hashes used for enforcing password reuse restrictions. A common name for this particular technique is DCSync.11

An example output from Get-AdReplAccount is below:

DistinguishedName: CN=TestUser,OU=Admins,OU=Users,DC=demo,DC=local

Sid: S-1-5-21-1432446722-301123485-1266542393-2012

Guid: 12321930-7c05-4011-8a3e-e0b9b6e04567

SamAccountName: TestUser

SamAccountType: User

UserPrincipalName: TestUser@demo.local

PrimaryGroupId: 513

SidHistory:

Enabled: True

UserAccountControl: NormalAccount

AdminCount: True

Deleted: False

LastLogonDate: 12/2/2021 1:41:46 PM

DisplayName: TestUser

GivenName: Test

Surname: User

Description: Admin Account

ServicePrincipalName:

SecurityDescriptor: DiscretionaryAclPresent, SystemAclPresent, DiscretionaryAclAutoInherited, SystemAclAutoInherited, DiscretionaryAclProtected, SelfRelative

Owner: S-1-5-21-1432446722-301123485-1266542393-512

Secrets

NTHash: 84a058676bb6d7de4237e18f09b91156

LMHash:

NTHashHistory:

Hash 01: 84a058676bb6d7de4237e18f09b91156

Hash 02: e047ebb3b7c463928c928fca95ac0ac8

Hash 03: 6dc3cdb3e559ef00d3521351ace7477e

Hash 04: a88355849f35fe7336de23a4ca3e6a9e

Hash 05: de9bde95677672295349aa6e1e857704

LMHashHistory:

Hash 01: 12227358dd7013c7dbdbd8fdcc0c6668

Hash 02: 6a028636a6f52491424586bb88357f7c

Hash 03: c13ef7347853dc3be7e7259fdc8818a1

Hash 04: 6635151746869ce485246037747adae1

Hash 05: 85543f498b007e07a3da662c8a9d450b

SupplementalCredentials:

ClearText:

NTLMStrongHash: de164e3465f163e846a5e1c22a5ac649

Kerberos:

Credentials:

DES_CBC_MD5

Key: 0013364f00003915

DES_CBC_CRC

Key: 0013364f00003915

OldCredentials:

DES_CBC_MD5

Key: 00002a46000004bc

DES_CBC_CRC

Key: 00002a46000004bc

Salt: demo.localTestUser

Flags: 0

KerberosNew:

Credentials:

AES256_CTS_HMAC_SHA1_96

Key: afd4d60e8d0920bc2f94d551f62f0ea2a17523bf2ff8ffb0fdade2a90389282f

Iterations: 4096

AES128_CTS_HMAC_SHA1_96

Key: f67c2bcbfcfa30fccb36f72dca22a817

Iterations: 4096

DES_CBC_MD5

Key: 00002f34000004ee

Iterations: 4096

DES_CBC_CRC

Key: 00002f34000004ee

Iterations: 4096

OldCredentials:

AES256_CTS_HMAC_SHA1_96

Key: b430783ab4c957cf6a03d3d348af27264c0d872932650ffca712d9ebcf778b9f

Iterations: 4096

AES128_CTS_HMAC_SHA1_96

Key: dc34bfd5e469edbeada77fac56aa35ae

Iterations: 4096

DES_CBC_MD5

Key: 0000345400000520

Iterations: 4096

DES_CBC_CRC

Key: 0000345400000520

Iterations: 4096

OlderCredentials:

AES256_CTS_HMAC_SHA1_96

Key: 26efd3593712e555f8366bb4b8aff097d09acd93c3a1b6d4ea03c578aad9e087

Iterations: 4096

AES128_CTS_HMAC_SHA1_96

Key: c38dfbd6c00b5f3b010a07f9e824fc38

Iterations: 4096

DES_CBC_MD5

Key: 000039a500000551

Iterations: 4096

DES_CBC_CRC

Key: 000039a500000551

Iterations: 4096

ServiceCredentials:

Salt: demo.localTestUser

DefaultIterationCount: 4096

Flags: 0

WDigest:

Hash 01: 83ed141ab0eaf1ff7694147ba97e1994

Hash 02: e73a8c05d4a7df53774bfa7ef8f0f574

Hash 03: 0c228c5816a79e561d999d489499a12a

Hash 04: 83ed141ab0eaf1ff7694147ba97e1994

Hash 05: e73a8c05d4a7df53774bfa7ef8f0f574

Hash 06: 4e7c5ec6ffb6100f0c7f0bc57749bc93

Hash 07: 83ed141ab0eaf1ff7694147ba97e1994

Hash 08: 10265b08a3bb710da516832eaf64368a

Hash 09: 10265b08a3bb710da516832eaf64368a

Key Credentials:

Credential Roaming

Created:

Modified:

Credentials:

Figure 10. Get-ADReplAccount example output

When executing the Get-ADReplAccount command, the threat actor specified the AD context to be targeted via the NamingContext parameter. This was necessary, as the threat actor was targeting multiple domains. The resulting output of each command was redirected to a text file and compressed as zip archives before exfiltration.

The fact that Get-ADReplAccount command includes not only the current NTLM hashes but also the hash history (i.e., hashes of previous passwords used by a user account) meant that the threat actor also had the ability to discover accounts that either reused the same passwords or used similar passwords when the account password was changed.

Credential Refresh

On some investigations, the dwell time of the threat actor spanned years. Given this extended period, it is logical to assume that some credentials obtained by the threat actor would be rotated during normal business operations. To combat this, the threat actor periodically “refreshed” their credential set by performing credential theft activities in an already compromised environment. At one victim, CrowdStrike identified multiple instances of domain credential theft months apart, each time with a different credential theft technique.

One of the credential theft techniques identified by CrowdStrike was the use of a PowerShell script to execute Mimikatz in-memory. While in-memory Mimikatz is not particularly unique, the script executed by the threat actor was heavily obfuscated and encrypted the output using AES256. CrowdStrike was able to reconstruct the PowerShell script from the PowerShell Operational event log as the script’s execution was logged automatically due to the use of specific keywords. CrowdStrike recommends that organizations upgrade PowerShell on their systems, as this functionality is only available with PowerShell version 5 and above.

In addition to refreshing the threat actor’s credentials, the threat actor would also refresh their understanding of the victim’s AD environment. Around the time when the threat actor executed Get-ADReplAccount, the threat actor also executed a renamed version of AdFind to output domain reconnaissance information. In this instance, AdFind was renamed to masquerade as a legitimate Windows binary. The usage of renamed AdFind is consistent with other industry reporting on this campaign.

In addition to using scripted commands, operators were repeatedly observed manually executing several standard PowerShell cmdlets to enumerate network information from AD, including Get-ADUser and Get-ADGroupMember to query specific members in the directory. This information provided the adversary with a list of accounts possessing particular privileges — in this case, the ability to make VPN connections — that would be subject to later credential stealing attempts and leveraged to access the victim at a later time.

Password Policies/Hygiene

In some cases, the threat actor was able to quickly return to the environment and essentially pick up where they left off, even though the organization had performed an enterprise-wide password reset, including a reset of all service accounts and the double-reset of the krbtgt account. CrowdStrike determined that in these cases, administrative users had “reset” their own password to the same password they previously used, essentially nullifying the impact of the enterprise-wide reset. This was possible even though the customer’s Active Directory was configured to require new passwords to be different from the previous five passwords for a given account. Unfortunately, this check only applies when a user is changing their password via the “password change” method — but if a “password reset” is performed (changing the password without knowing the previous password), this check is bypassed for an administrative user or a Windows account that has the Reset Password permission on a user’s account object.12 Since the Get-ADReplAccount cmdlet described above included the NTHashHistory values (i.e., previous password hashes) for user accounts, CrowdStrike was able to verify that some administrative accounts indeed had the exact same password hash showing up multiple times in the password history, as well as in the current NTHash value.

Close Out

The StellarParticle campaign, associated with the COZY BEAR adversary group, demonstrates this threat actor’s extensive knowledge of Windows and Linux operating systems, Microsoft Azure, O365, and Active Directory, and their patience and covert skill set to stay undetected for months — and in some cases, years.

A special thank you to the CrowdStrike Incident Response and CrowdStrike Intelligence teams for helping make this blog possible, especially Ryan McCombs, Ian Barton, Patrick Bennet, Alex Parsons, Christopher Romano, Jackson Roussin and Tom Goldsmith.

Endnotes

- https://us-cert.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/publications/CISA_Fact_Sheet-Russian_SVR_Activities_Related_to_SolarWinds_Compromise_508C.pdf

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/partner-center/permissions-overview

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/partner-center/announcements/2021-december#9

- https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1546/003/

- CrowdStrike Premium Intelligence Report

- https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1213/001/

- https://dirkjanm.io/azure-ad-privilege-escalation-application-admin/

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/active-directory/conditional-access/block-legacy-authentication

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/exchange/applicationimpersonation-role-exchange-2013-help

- https://github.com/MichaelGrafnetter/DSInternals

- https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1003/006/

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/openspecs/windows_protocols/ms-samr/bbee5135-3db2-4824-873a-55104c3610ad

MITRE ATT&CK Framework

The following table maps TTPs covered in this article to the MITRE ATT&CK® framework.

| Tactic | Technique | Observable |

| Credential Access | T1003.006 OS Credential Dumping: DCSync | The threat actor obtained Active Directory credentials through domain replication protocols using the Get-ADReplAccount command from DSInternals |

| Credential Access | T1003.001: OS Credential Dumping: LSASS Memory | The threat actor used a heavily obfuscated PowerShell script to execute the Mimikatz commands ‘privilege::debug sekurlsa::logonpasswords “lsadump::lsa /patch”‘ in-memory and encrypt the output |

| Initial Access / Persistence | T1078.003: Valid Accounts: Local Accounts | A local account was used by the Threat Actor to establish a SSH tunnel into the internal network environment |

| Initial Access / Persistence | T1133: External Remote Services | The threat actor used VPNs to gain access to systems and persist in the environment |

| Credential Access | T1555.003: Credentials from Password Stores: Credentials from Web Browsers | The threat actor exported saved passwords from user’s Chrome browser installations |

| Credential Access | T1539: Steal Web Session Cookie | The threat actor stole web session cookies from end user workstations and used them to access cloud resources |

| Lateral Movement | T1021.001: Remote Services: Remote Desktop Protocol | The threat actor used both privileged and non-privileged accounts for RDP throughout the environment, depending on the target system |

| Initial Access, Persistence | T1078.004: Valid Accounts: Cloud Accounts | The threat actor used accounts with Delegated Administrator rights to access other O365 tenants. The Threat actor also used valid accounts to create persistence within the environment. |

| Persistence | T1546.003: Event Triggered Execution: Windows Management Instrumentation Event Subscription | TrailBlazer was configured to execute after a reboot via a command-line event consumer |

| Defense Evasion | T1036.005: Masquerading: Match Legitimate Name or Location | The threat actor renamed their utilities to masquerade as legitimate system binaries (AdFind as svchost.exe), match the system’s role (GoldMax), or appear legitimate (TrailBlazer as an apparent Adobe utility). Additionally, the threat actor renamed their systems prior to connecting to victim’s VPNs to match the victim’s system naming convention |

| Discovery | T1087.002: Account Discovery: Domain Account

|

The threat actor used AdFind, standard PowerShell cmdlets, and custom tooling to identify various pieces of information from Active Directory |

| Defense Evasion / Lateral Movement | T1550.001: Use Alternate Authentication Material: Application Access Token | The threat actor used compromised service principals to make changes to the Office 365 environment. |

| Collection | T1213.: Data from Information Repositories: | The threat actor accessed data from Information Repositories |

| Persistence | T1098.001: Account Manipulation: Additional Cloud Credentials | The threat actor added credentials to O365 Service Principals |

| Persistence | T1078.004: Valid Accounts: Cloud Accounts | The threat actor created new O365 Service Principals to maintain access to victim’s environments |

| Discovery | T1057: Process Discovery | The threat actor regularly interrogated other systems using tasklist.exe |

| Reconnaissance | T1595.001: Active Scanning: Scanning IP Blocks | The threat actor probed external services in an attempt to regain access to the environment |

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

| Indicator | Details |

| http://satkas.waw[.]pl/rainloop/forecast | TrailBlazer C2 |

| 1326932d63485e299ba8e03bfcd23057f7897c3ae0d26ed1235c4fb108adb105 | TrailBlazer SHA256 |

| vm-srv-1.gel.ulaval.ca | GoldMax C2 |

| 2a3b660e19b56dad92ba45dd164d300e9bd9c3b17736004878f45ee23a0177ac | GoldMax SHA256 |

| 156.96.46.116 | TA Infrastructure |

| 188.34.185.85 | TA Infrastructure |

| 212.103.61.74 | TA Infrastructure |

| 192.154.224.126 | TA Infrastructure |

| 23.29.115.180 | TA Infrastructure |

| 104.237.218.74 | TA Infrastructure |

| 23.82.128.144 | TA Infrastructure |

Additional Resources

- Read about the latest trends in threat hunting and more in the 2021 Threat Hunting Report or simply download the report now.

- Learn more about Falcon OverWatch proactive managed threat hunting.

- Watch this video to see how Falcon OverWatch proactively hunts for threats in your environment.

- Learn more about the CrowdStrike Falcon® platform by visiting the product webpage.

- Test CrowdStrike next-gen AV for yourself. Start your free trial of Falcon Prevent™ today.