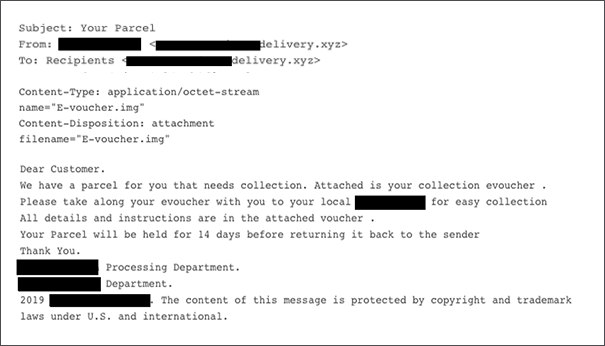

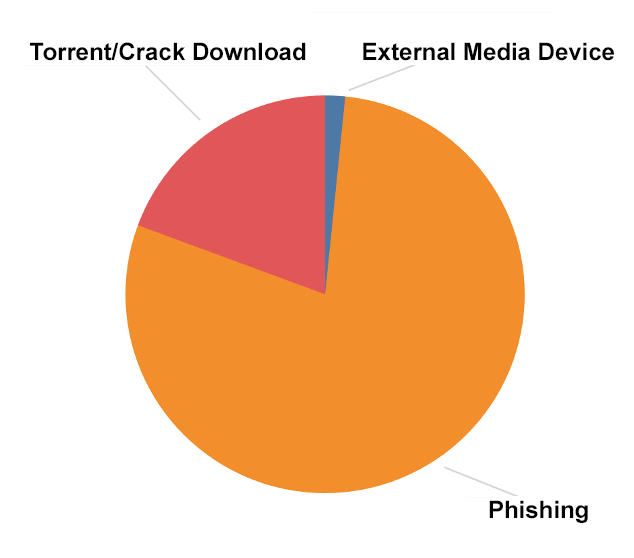

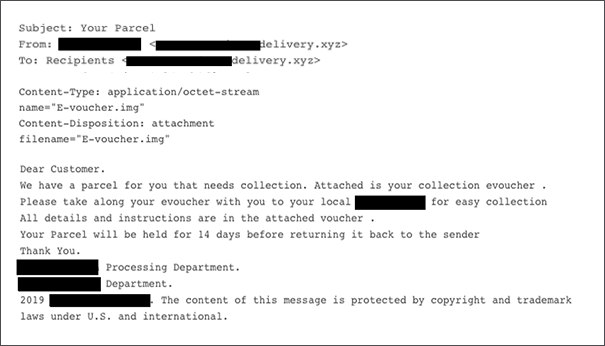

Throughout 2019 and the beginning of 2020, the CrowdStrike® Falcon CompleteTM team continuously observed a spike in the delivery of weaponized disk image files. Files such as ISO and IMG were sent to infect systems with the goal of delivering remote access trojans (RATs) as well as a few other malware variants. We’ve identified that these files are typically delivered via phishing campaigns as an attachment or link — a malicious URL in the body of the email or within crack software downloads. Figure 1. Phishing contents sample. The delivery company did not send this email.

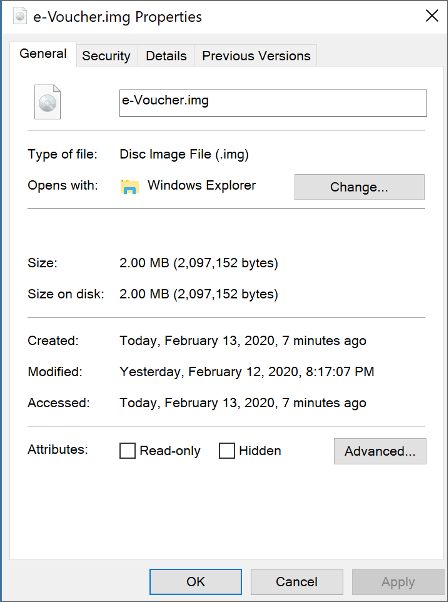

The attachment in this sample is only 2MB, which raises a flag immediately as disk images are typically larger in size.

Figure 1. Phishing contents sample. The delivery company did not send this email.

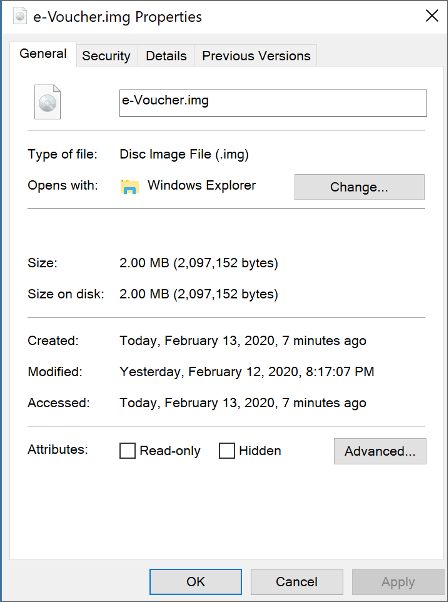

The attachment in this sample is only 2MB, which raises a flag immediately as disk images are typically larger in size. Figure 2. IMG file properties

Double-clicking on the file allows Windows 8 and Windows 10 to mount the IMG file natively to the next available drive. This sample uses a PDF icon as a disguise.

Figure 2. IMG file properties

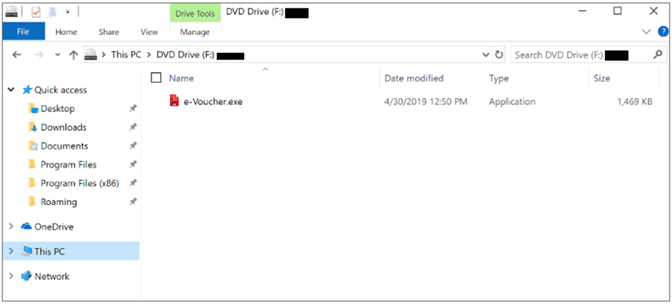

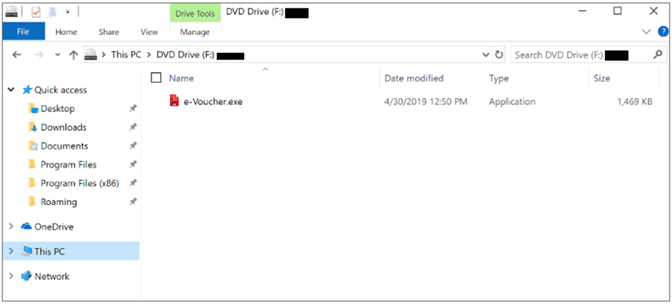

Double-clicking on the file allows Windows 8 and Windows 10 to mount the IMG file natively to the next available drive. This sample uses a PDF icon as a disguise. Figure 3. IMG file mounted on disk

Figure 3. IMG file mounted on disk

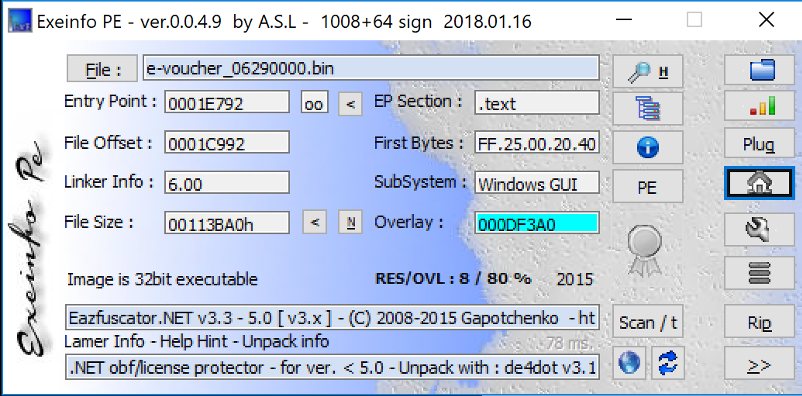

Figure 4. Exeinfo PE against binary

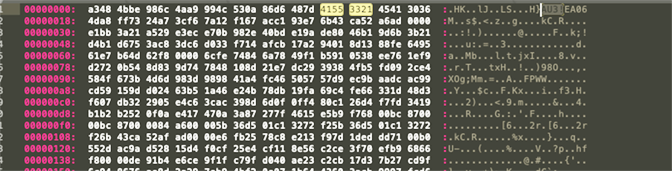

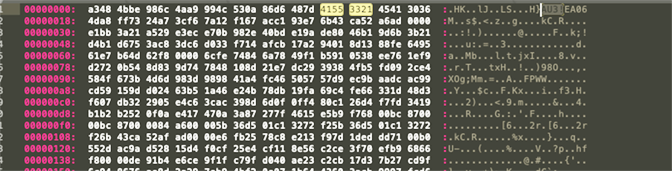

Dumping the rcdata resource and reviewing the strings shows AU3!, a common string seen in AutoIT-developed scripts.

Figure 4. Exeinfo PE against binary

Dumping the rcdata resource and reviewing the strings shows AU3!, a common string seen in AutoIT-developed scripts.

Figure 5. Hexdump of

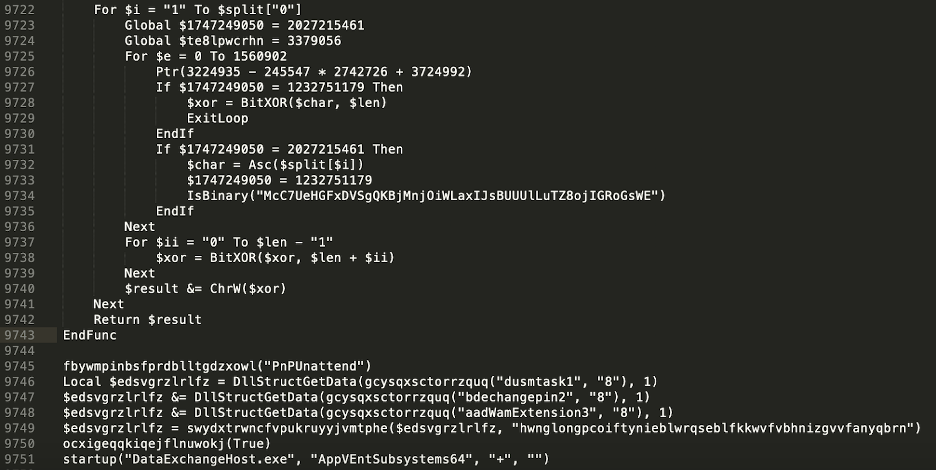

The AutoIT script is obfuscated, and it is used as a dropper to eventually load the NanoCore RAT on the intended system.

Figure 5. Hexdump of

The AutoIT script is obfuscated, and it is used as a dropper to eventually load the NanoCore RAT on the intended system.

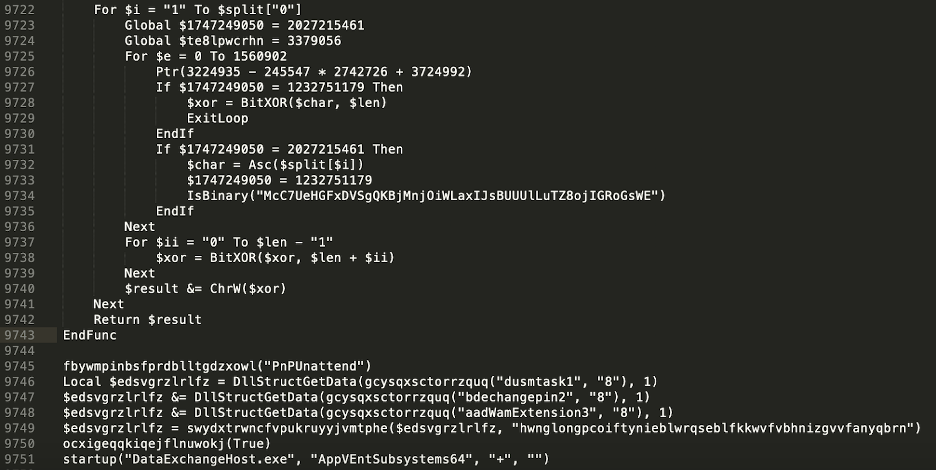

Figure 6. Snippet of obfuscated AutoIt script

Beginning on line 9746 in Figure 6, we can see the following three resources:

Figure 6. Snippet of obfuscated AutoIt script

Beginning on line 9746 in Figure 6, we can see the following three resources:

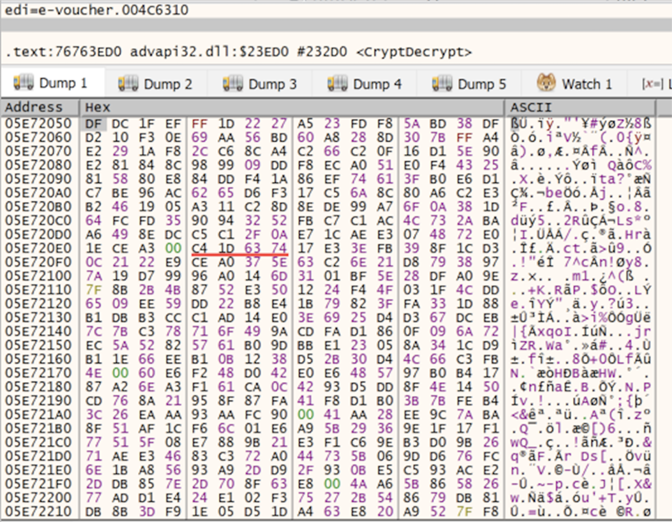

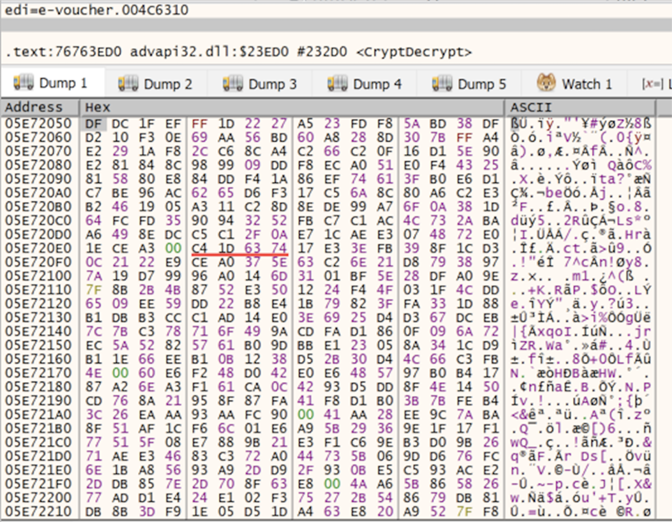

Figure 7. Encrypted stream prior to CryptDecrypt

Figure 7. Encrypted stream prior to CryptDecrypt

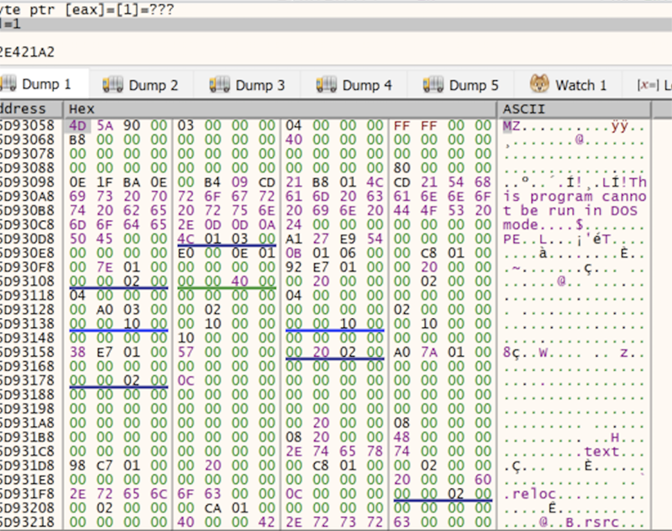

Figure 8. Contents decrypted after CryptDecrypt returns

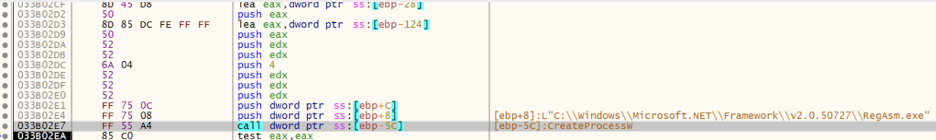

Once the contents are decrypted, it will then use the CreateProcessW function to spawn the legitimate process RegAsm.exe in a suspended state using the process creation flag

Figure 8. Contents decrypted after CryptDecrypt returns

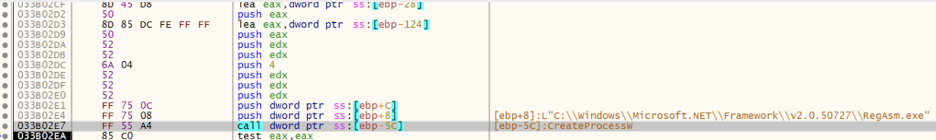

Once the contents are decrypted, it will then use the CreateProcessW function to spawn the legitimate process RegAsm.exe in a suspended state using the process creation flag  Figure 9. x32dbg debugger CreateProcessW function starts RegAsm.exe in suspended state

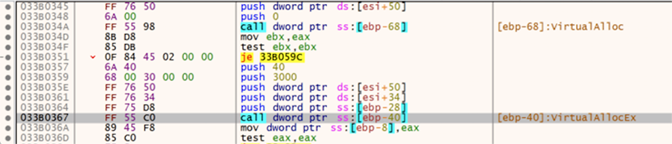

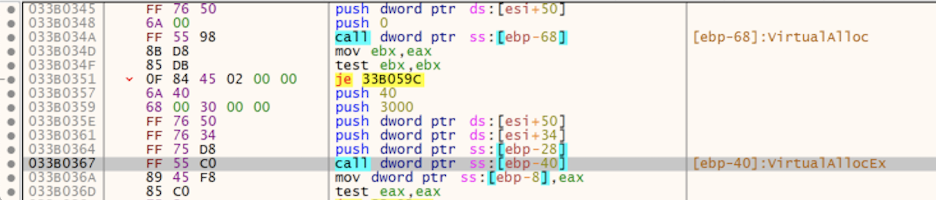

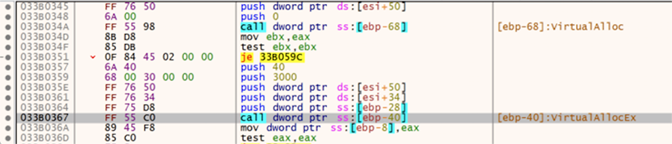

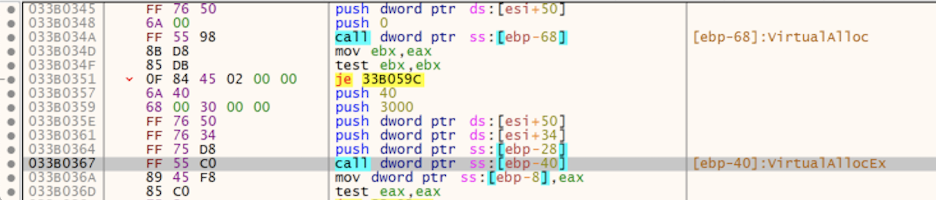

Shortly after, it proceeds to allocate memory space for the malicious payload that was decrypted earlier. This memory region is created with memory protection of

Figure 9. x32dbg debugger CreateProcessW function starts RegAsm.exe in suspended state

Shortly after, it proceeds to allocate memory space for the malicious payload that was decrypted earlier. This memory region is created with memory protection of  Figure 10. x32dbg debugger VirtualAllocEx allocating memory space

Last, the WriteProcessMemory call is seen to finally write the contents into this newly created memory region.

Figure 10. x32dbg debugger VirtualAllocEx allocating memory space

Last, the WriteProcessMemory call is seen to finally write the contents into this newly created memory region.

Figure 11. x32dbg debugger WriteProcessMemory function writing into memory region

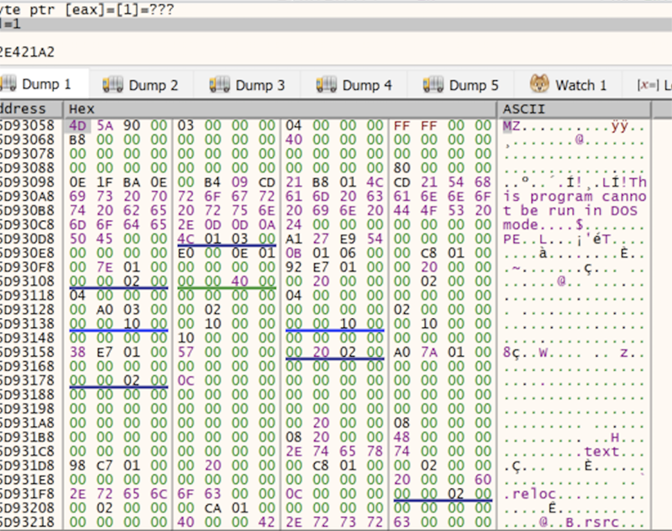

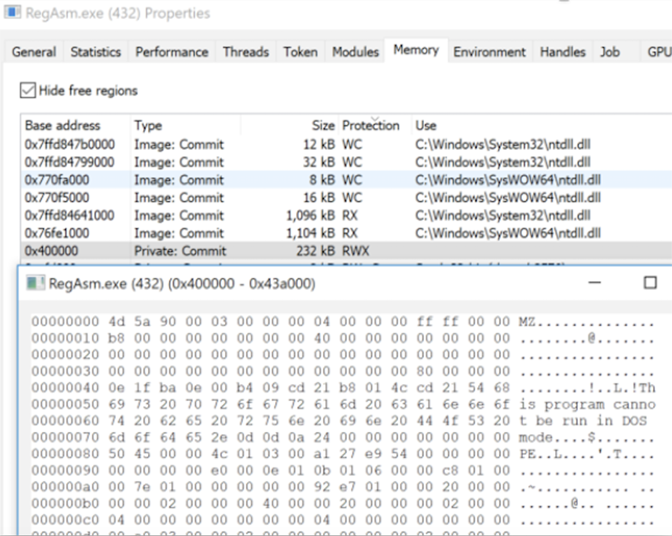

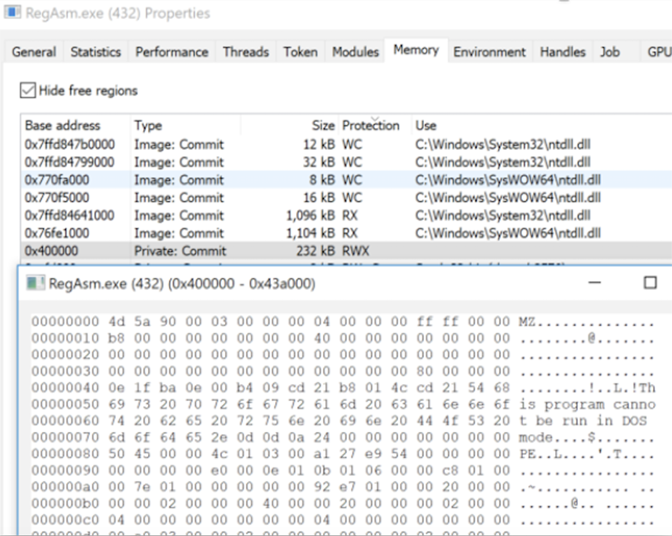

Inspecting

Figure 11. x32dbg debugger WriteProcessMemory function writing into memory region

Inspecting  Figure 12. ProcessHacker showing memory region injected with malicious code

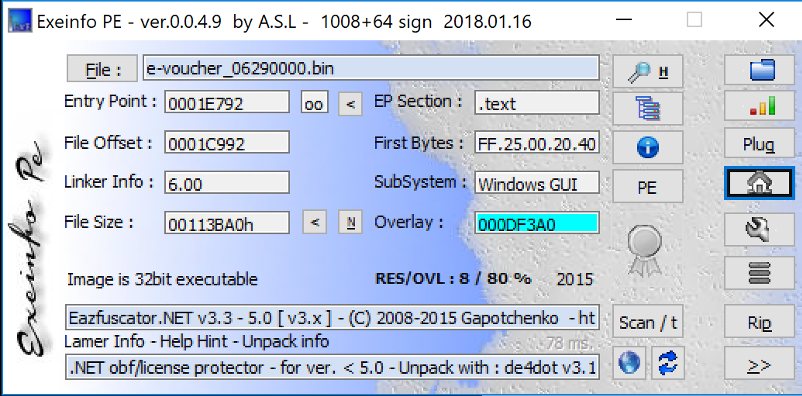

After dumping the malicious code out of memory, we can confirm that it is a .NET built binary packed with Eazfuscator.

Figure 12. ProcessHacker showing memory region injected with malicious code

After dumping the malicious code out of memory, we can confirm that it is a .NET built binary packed with Eazfuscator.

Figure 13. Exeinfo displaying packer information on dumped process

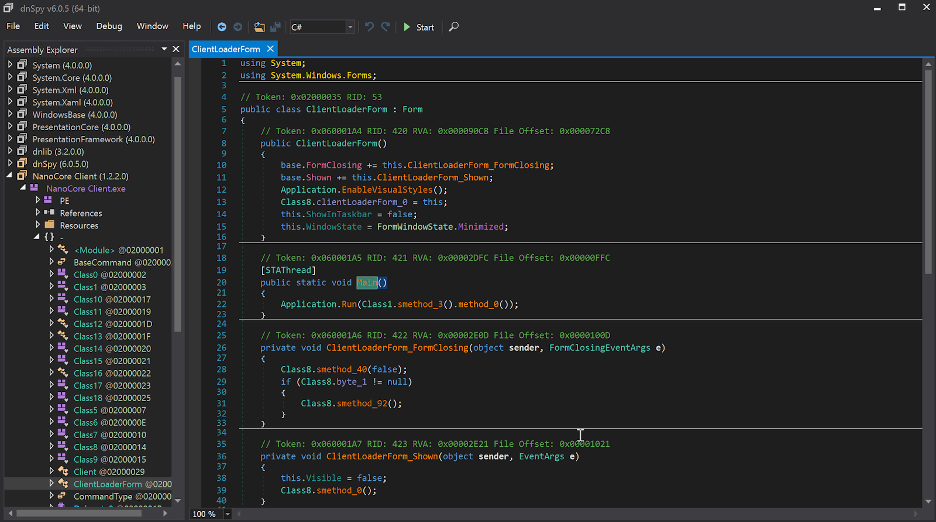

Running de4dot against this copy is able to deobfuscate to see readable strings.

Figure 13. Exeinfo displaying packer information on dumped process

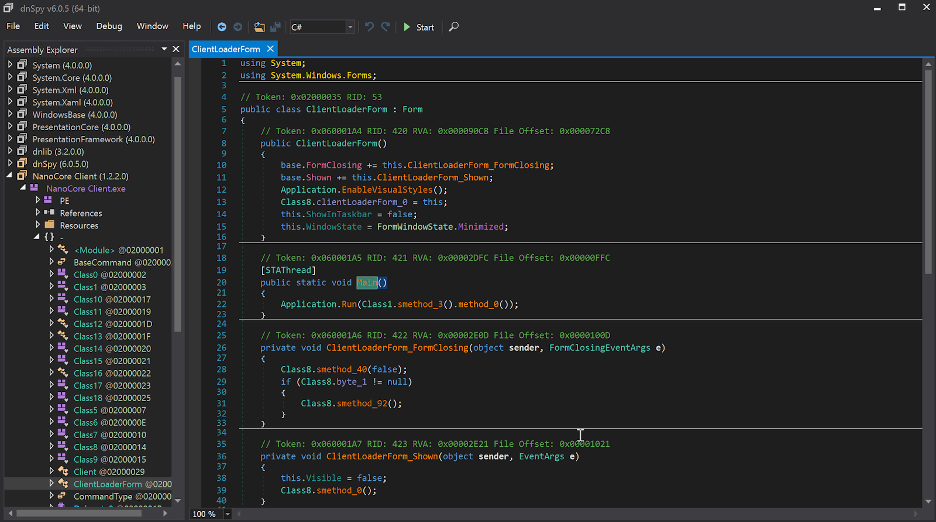

Running de4dot against this copy is able to deobfuscate to see readable strings. Figure 14. DnsSpy after deobfuscation

The malware then proceeds to drop a copy of itself to the path

Figure 14. DnsSpy after deobfuscation

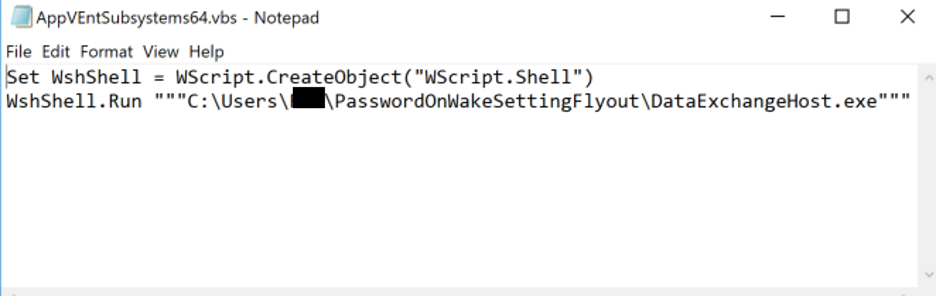

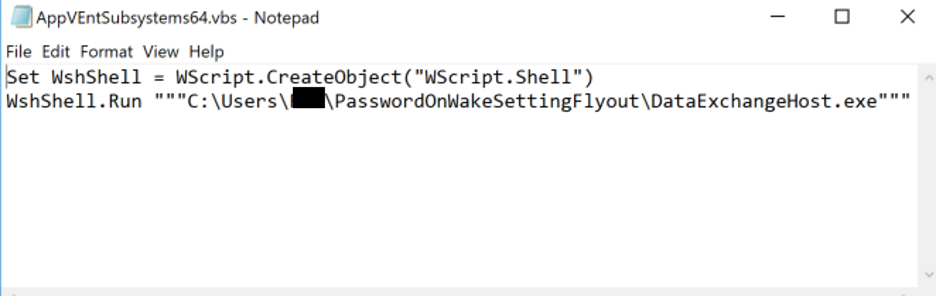

The malware then proceeds to drop a copy of itself to the path Figure 15. VBS script contents

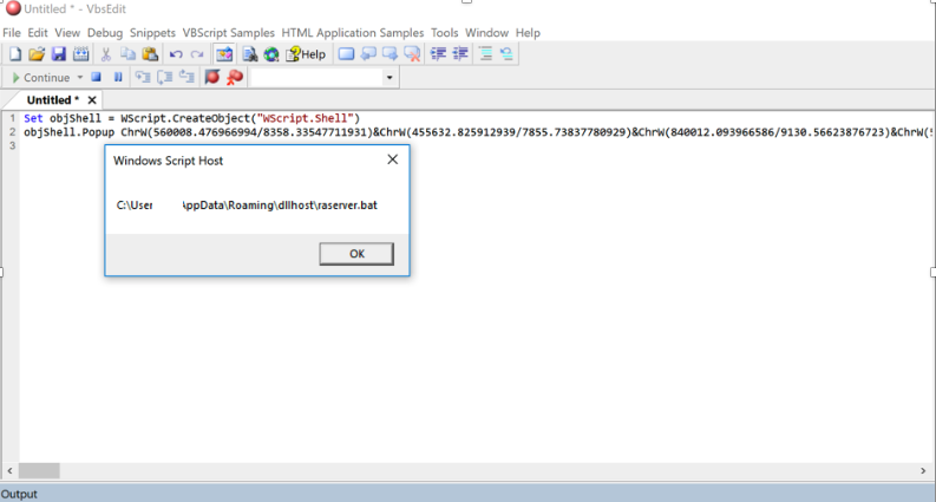

The Falcon Complete Team has seen variations of the script above being obfuscated with the same ultimate goal such as in Figure 16.

Figure 15. VBS script contents

The Falcon Complete Team has seen variations of the script above being obfuscated with the same ultimate goal such as in Figure 16.

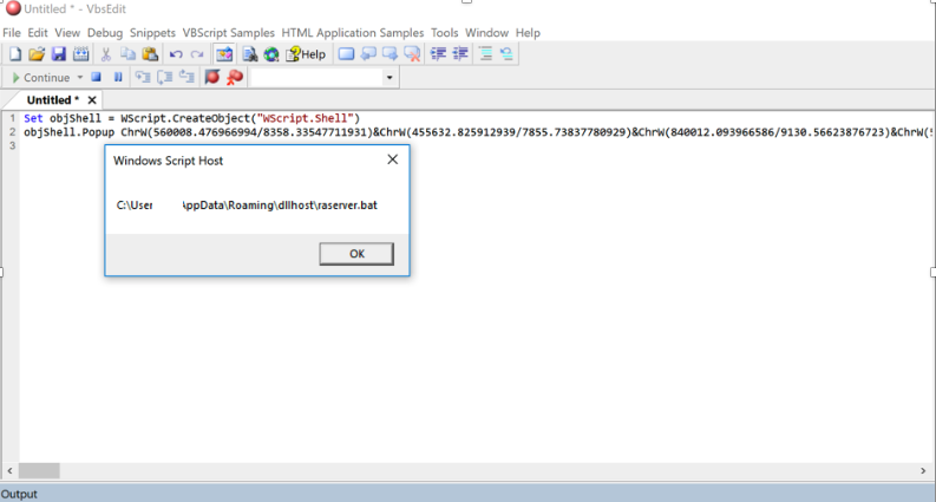

Figure 16. VbsEdit debugging obfuscated script

A copy of

Figure 16. VbsEdit debugging obfuscated script

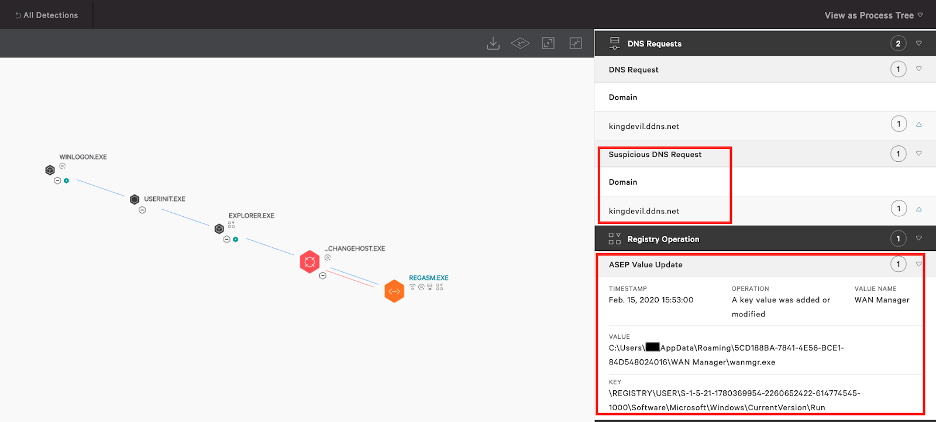

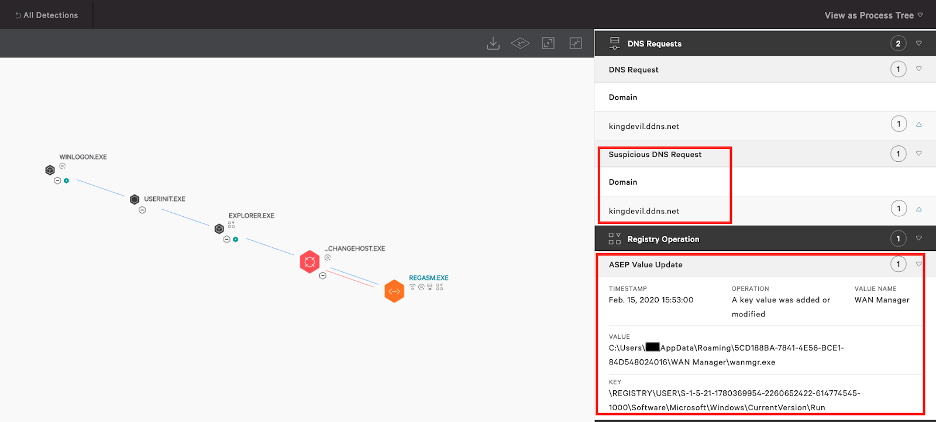

A copy of  Figure 17. Falcon Process Tree displaying Registry Operations and DNS request

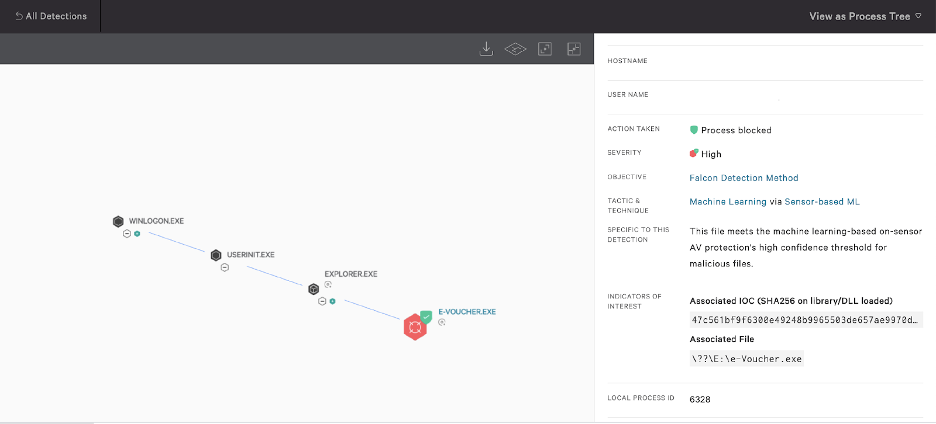

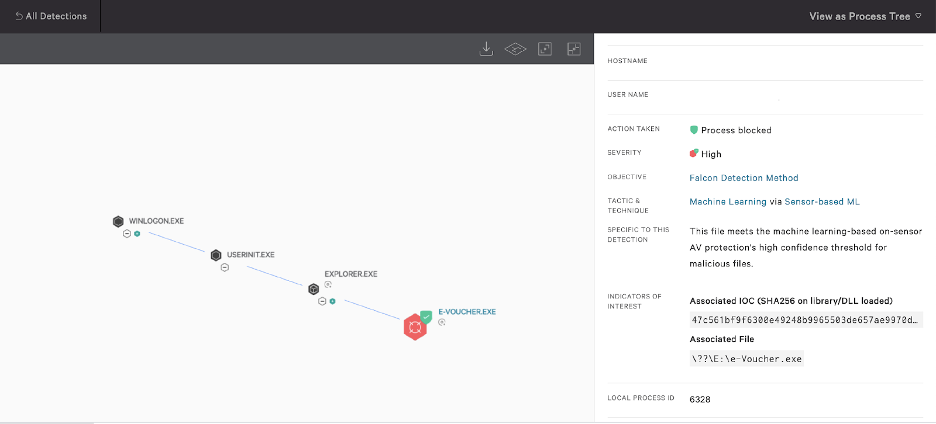

The functionality of NanoCore RAT has been covered heavily, so this blog will not focus on it. Figure 18 shows the same detection in Falcon’s UI but this time being prevented after running the same sample with the detection and prevention settings set to “Aggressive.”

Figure 17. Falcon Process Tree displaying Registry Operations and DNS request

The functionality of NanoCore RAT has been covered heavily, so this blog will not focus on it. Figure 18 shows the same detection in Falcon’s UI but this time being prevented after running the same sample with the detection and prevention settings set to “Aggressive.”

Figure 18. Prevention policy enabled

Remediation:

Figure 18. Prevention policy enabled

Remediation: Remediation Difficulty

The remediation can be summarized in the following steps:

Remediation Difficulty

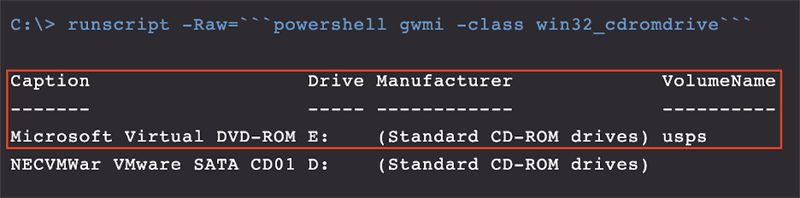

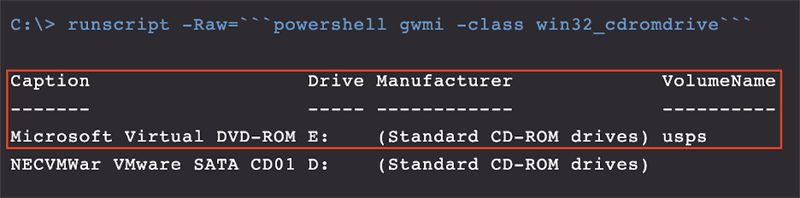

The remediation can be summarized in the following steps: Figure 19. Output of WMI command

Now that we’ve identified what’s mounted, we are using the PowerShell

Figure 19. Output of WMI command

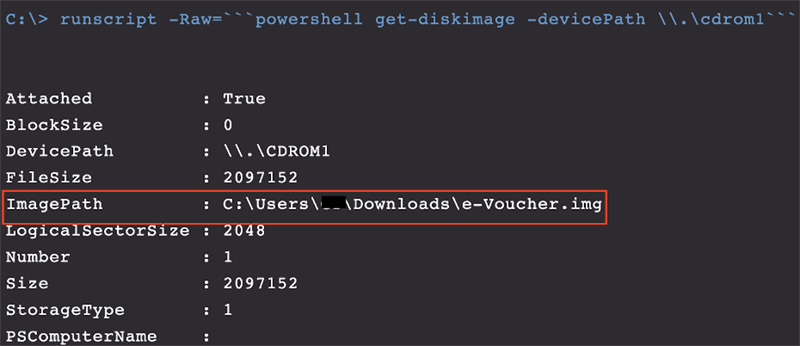

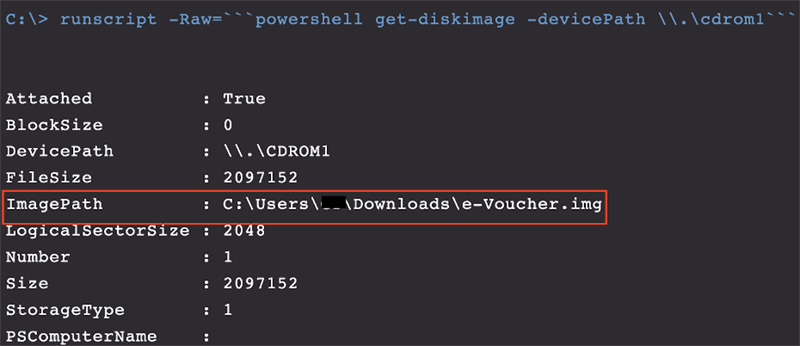

Now that we’ve identified what’s mounted, we are using the PowerShell  Figure 20. Output of Powershell

Use the image path obtained from the output received on the previous command to unmount this virtual disk. If the process is actively running, terminate it first. Also, you first need to unmount this disk or else you will not be able to remove it.

Figure 20. Output of Powershell

Use the image path obtained from the output received on the previous command to unmount this virtual disk. If the process is actively running, terminate it first. Also, you first need to unmount this disk or else you will not be able to remove it. Figure 21. Unmounting IMG file using Dismount-DiskImage

Figure 21. Unmounting IMG file using Dismount-DiskImage

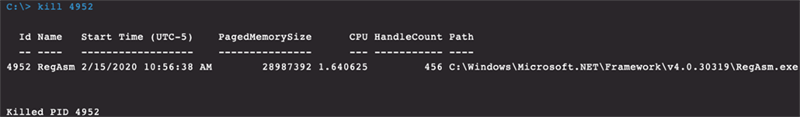

Figure 22. Terminated process output

Figure 22. Terminated process output

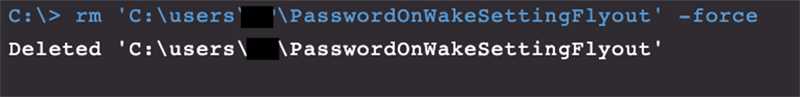

Figure 23. Deleting registry entry successfully

Figure 23. Deleting registry entry successfully

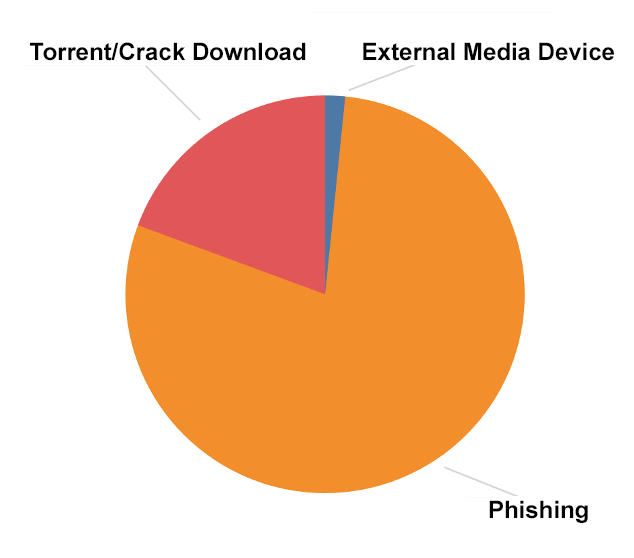

Figure 24. Removing artifacts from disk output

Figure 24. Removing artifacts from disk output

Figure 25. Removing artifacts from disk output

Figure 25. Removing artifacts from disk output

Figure 26. Removing artifacts from disk output

This completes the remediation steps we execute to tackle such variants when discovered. Note that in this scenario, we’ve purposely turned off the prevention policy while leaving the detection policy turned on for illustrative purposes.

Figure 26. Removing artifacts from disk output

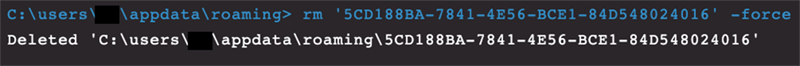

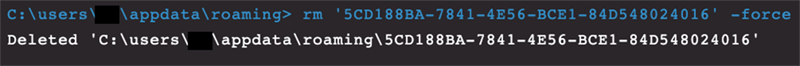

This completes the remediation steps we execute to tackle such variants when discovered. Note that in this scenario, we’ve purposely turned off the prevention policy while leaving the detection policy turned on for illustrative purposes. Figure 27. Malware family breakdown

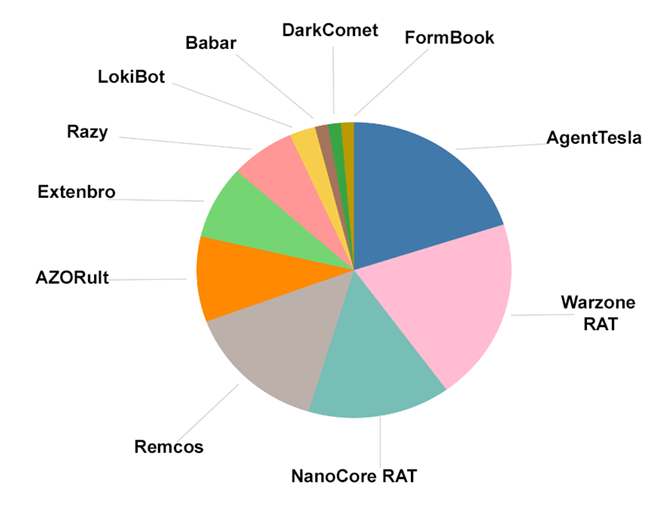

The entry vector for these have primarily been phishing emails, where users download Torrent/Crack software onto their machines disguised as movies, games or music but that actually contains infected USB media.

Figure 27. Malware family breakdown

The entry vector for these have primarily been phishing emails, where users download Torrent/Crack software onto their machines disguised as movies, games or music but that actually contains infected USB media. Figure 28. Entry vector breakdown

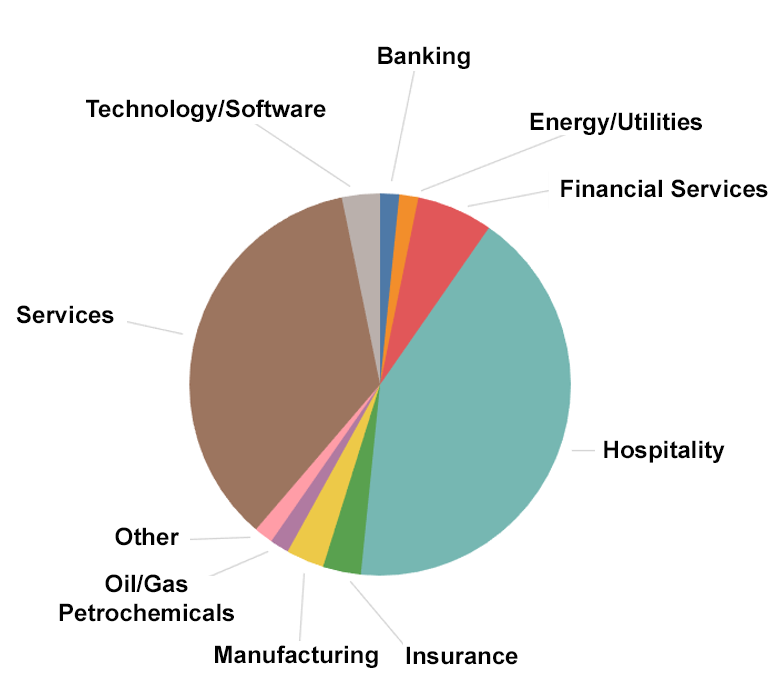

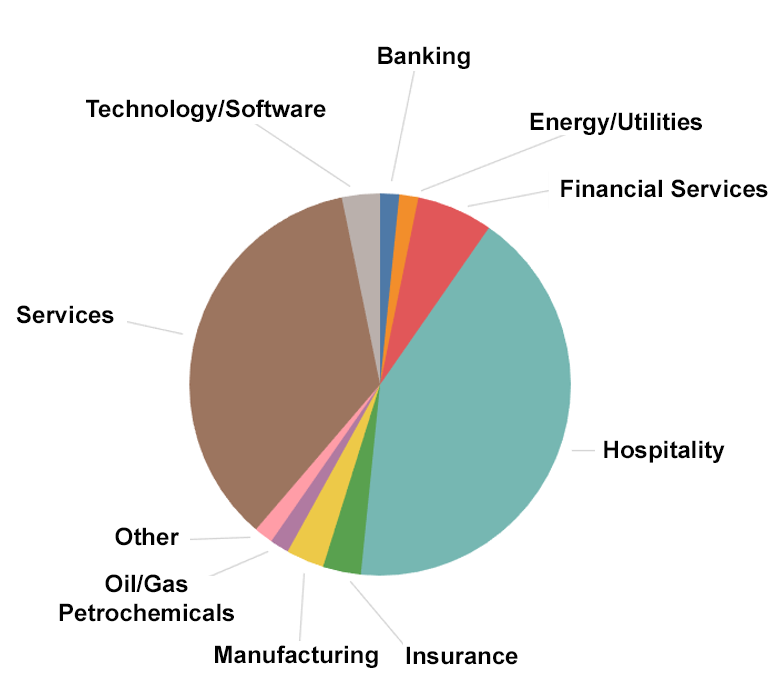

In regard to verticals, we’ve noticed these campaigns are widely spread across multiple verticals, with the hospitality sector being the most affected.

Figure 28. Entry vector breakdown

In regard to verticals, we’ve noticed these campaigns are widely spread across multiple verticals, with the hospitality sector being the most affected. Figure 29. Affected verticals observed

Figure 29. Affected verticals observed

Cyber criminals have been taking advantage of built-in Windows capabilities to mount disk image files once they are opened by the end user. There are multiple disk image file formats, but we have seen ISO and IMG files being abused the most. A disk image is essentially a virtual copy of a physical disk that houses all of the files and requires that it be mounted in order to access its contents. The advantages of using disk images, combined with the easy access to purchasing RATs, make this a preferred and effective method for cybercriminals. In this blog, I dissect a campaign that uses this method to compromise a system, providing insight into what the CrowdStrike Falcon®Complete team has observed since 2019. I will also provide step-by-step remediation along with recommendations for how to implement this approach in your network.

Parcel-themed Phishing Email Scenario

The chain starts with a simple email containing a disk image file (.IMG) to socially engineer the victim into viewing the contents. The message seems to be coming from a worldwide package delivery company. Figure 1. Phishing contents sample. The delivery company did not send this email.

Figure 1. Phishing contents sample. The delivery company did not send this email.

Figure 2. IMG file properties

Figure 2. IMG file properties

Figure 3. IMG file mounted on disk

Figure 3. IMG file mounted on diskAnalysis

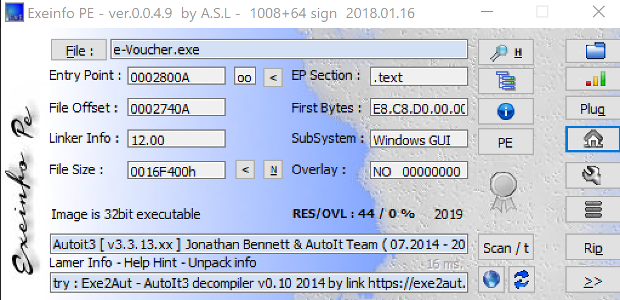

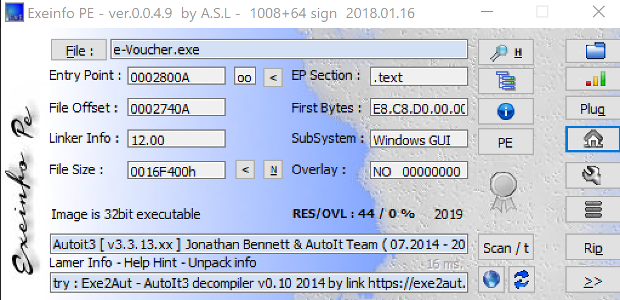

Exeinfo PE identified the binary as a compiled AutoIT script version 3. AutoIT is a scripting language used to automate Windows GUI tasks. Cybercriminals would first compile these scripts into an executable using the Aut2Exe compiler and further convert it into a disk image file to then distribute it widely in campaigns. Figure 4. Exeinfo PE against binary

Figure 4. Exeinfo PE against binary e-voucher.exe Figure 5. Hexdump of

Figure 5. Hexdump of e-voucher.exe Figure 6. Snippet of obfuscated AutoIt script

Figure 6. Snippet of obfuscated AutoIt scriptdusmtask1

bdechangepin2

aadWamExtension3

The script merges these three resources and passes the key “hwnglongpcoiftynieblwrqseblfkkwvfvbhnizgvvfanyqbrn” as the second parameter to the function swydxtrwncfvpukruyyjvmtphe(). To decrypt, it creates a hash using CryptCreateHash with this key. Consequently, it then uses the function CryptDeriveKey and creates a separate key from the results of CryptCreateHash. Finally, CryptDecrypt is used to decrypt the resource.

Figure 7. Encrypted stream prior to CryptDecrypt

Figure 7. Encrypted stream prior to CryptDecrypt Figure 8. Contents decrypted after CryptDecrypt returns

Figure 8. Contents decrypted after CryptDecrypt returns0x00000004 (CREATE_SUSPENDED)

Figure 9. x32dbg debugger CreateProcessW function starts RegAsm.exe in suspended state

Figure 9. x32dbg debugger CreateProcessW function starts RegAsm.exe in suspended state0x40 (PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE)

Figure 10. x32dbg debugger VirtualAllocEx allocating memory space

Figure 10. x32dbg debugger VirtualAllocEx allocating memory space Figure 11. x32dbg debugger WriteProcessMemory function writing into memory region

Figure 11. x32dbg debugger WriteProcessMemory function writing into memory regionRegAsm.exe using ProcessHacker shows the memory region 0x400000 that was created earlier filled with the payload. The sample is using a well-known technique to hollow out RegAsm.exe and inject its payload.

Figure 12. ProcessHacker showing memory region injected with malicious code

Figure 12. ProcessHacker showing memory region injected with malicious code Figure 13. Exeinfo displaying packer information on dumped process

Figure 13. Exeinfo displaying packer information on dumped process

Figure 14. DnsSpy after deobfuscation

Figure 14. DnsSpy after deobfuscation

C:\Users\username\PasswordOnWakeSettingFlyout\DataExchangeHost.exe

In addition, it creates persistence by using a URL shortcut in the StartUp folder that points to the copy of NanoCore RAT to survive reboot. A malicious VBS script named AppVEntSubsystems64.vbs is also dropped in the same directory where DataExchangeHost.exe resides.

Figure 15. VBS script contents

Figure 15. VBS script contents Figure 16. VbsEdit debugging obfuscated script

Figure 16. VbsEdit debugging obfuscated scriptRegAsm.exe is dropped onto disk and is added to the Run key to boot on user logon, as seen in Falcon’s Process Tree viewer. Falcon also logs the network connection used as the C2 in this sample, as seen in Figure 17.

Figure 17. Falcon Process Tree displaying Registry Operations and DNS request

Figure 17. Falcon Process Tree displaying Registry Operations and DNS request

Figure 18. Prevention policy enabled

Figure 18. Prevention policy enabled

Remediation Difficulty

Remediation Difficulty

- Identify and confirm detection originates from a virtual mounted drive:

- Find the location of the disk image where it resides

- Unmount the virtual drive

- Remove the IMG from disk

- Terminate the injected process

- Remove the registry entry

- Remove related directories and files

STEP 1: Identify and Remove the Mounted Disk Image

In order to identify, confirm and remove the IMG file that was mounted, we first use the class Win32_CDROMDrive from WMI in Figure 19 to provide us with information on what is currently mounted, along with the drive letter and the volume name.

Figure 19. Output of WMI command

Figure 19. Output of WMI commandGet-DiskImage cmdlet to get the objects associated with the IMG file which will indicate where this file resides on disk.

Figure 20. Output of Powershell

Figure 20. Output of Powershell Get-DiskImage command

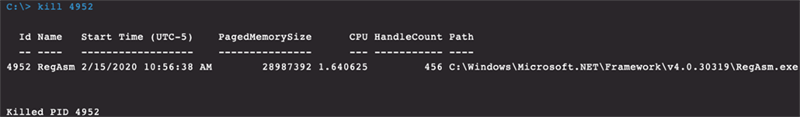

STEP 2:

Terminate the Injected Process From Falcon’s Process Tree, we discovered the injected RegAsm.exe process was running under the process ID 4952. Proceed to terminate this process using the built-in “kill” command using the process ID discovered.

Figure 22. Terminated process output

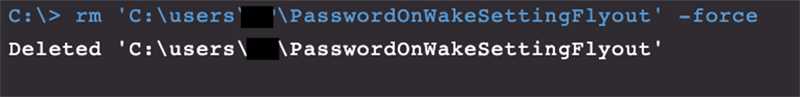

Figure 22. Terminated process outputSTEP 3:

Remove the Registry Entry Next, we remove the registry entry that was created at infection by using the PowerShell command in Figure 23.

STEP 4:

Remove Related Directories and Files

Last, we remove all remaining directories and files that were discovered during timeline analysis of the system.

Figure 24. Removing artifacts from disk output

Figure 24. Removing artifacts from disk output Figure 25. Removing artifacts from disk output

Figure 25. Removing artifacts from disk outputWithin the scope of our service, we’ve been able to observe Warzone, NanoCore and Agent Tesla RATs to be the most preferred by cybercriminals among others as seen in Figure 27.

Figure 27. Malware family breakdown

Figure 27. Malware family breakdown

Figure 28. Entry vector breakdown

Figure 28. Entry vector breakdown

Figure 29. Affected verticals observed

Figure 29. Affected verticals observed

Recommendations

- Gain advanced visibility across your endpoints with an

endpoint detection and response (EDR)

solution such as the

CrowdStrike

Falcon® platform.

Turn on

next-gen antivirus (NGAV)

preventative measures to stop malware. - Leverage a Layer 7 firewall that can perform deep packet inspection to examine the traffic and block P2P protocol types.

- Observe inbound emails received during a short span of time to see the volume of disk image files being delivered as attachments. If applicable, block known disk images file types such as IMG, ISO, DAA, VHD, CDI, VMDK, etc., to reduce the attack surface.

- Leverage a proxy to proactively block sites that are uncategorized/unknown, as we’ve seen new sites registered shortly before phishing campaigns are executed.

- Incorporate a phishing awareness program internally, and routinely test employees with phishing test emails.

Additional Resources

- Learn more about the CrowdStrike Falcon® platform by visiting the webpage.

- Learn how you can raise your organization’s cybersecurity maturity to the highest level immediately with

CrowdStrike Falcon® CompleteTM. - Learn how you can take

advantage of automated malware analysis and sandbox by visiting the CrowdStrike Falcon SandboxTM webpage. - Learn how CrowdStrike combines automated analysis with human intelligence to enable security teams to get ahead of the attacker's next move by visiting the CROWDSTRIKE FALCON® INTELLIGENCETM webpage.

- Get a full-featured free trial of CrowdStrike Falcon® Prevent™ and learn how true next-gen AV performs against today’s most sophisticated threats.

![Helping Non-Security Stakeholders Understand ATT&CK in 10 Minutes or Less [VIDEO]](https://assets.crowdstrike.com/is/image/crowdstrikeinc/video-ATTCK2-1?wid=530&hei=349&fmt=png-alpha&qlt=95,0&resMode=sharp2&op_usm=3.0,0.3,2,0)

![Qatar’s Commercial Bank Chooses CrowdStrike Falcon®: A Partnership Based on Trust [VIDEO]](https://assets.crowdstrike.com/is/image/crowdstrikeinc/Edward-Gonam-Qatar-Blog2-1?wid=530&hei=349&fmt=png-alpha&qlt=95,0&resMode=sharp2&op_usm=3.0,0.3,2,0)