CrowdStrike recently announced the addition of Falcon Identity Threat Protection and Falcon Identity Threat Detection to its GovCloud-1 environment, making both available to U.S. public sector organizations that require Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program (FedRAMP) Moderate or Impact Level 4 (IL-4) authorization. This includes U.S. federal agencies, U.S. state and local governments and the Defense Industrial Base (DIB). On May 12, 2021, the White House released an Executive Order (EO) on Improving the Nation’s Cybersecurity to offer guidance on security best practices including how the federal government must advance toward a Zero Trust Architecture to keep pace with today’s dynamic and increasingly sophisticated cyber threat environment. CrowdStrike believes Zero Trust principles and identity protection must be applied properly to both hybrid and multi-cloud environments. Identity protection must be all-encompassing and contextually aware of a customer’s on-premises and cloud environments, as well as other identity providers. Lacking visibility in part of the architecture or part of the authentication flow can lead to breaches. Falcon Identity Threat Detection is CrowdStrike’s solution for detecting identity-based attacks with zero dependency on logs. Extending that solution, Falcon Identity Threat Protection helps detect and prevent identity-based solutions in real time. In addition, Falcon Identity Threat Protection integrates with the top identity directories, including Active Directory, enabling customers to enforce multifactor authentication (MFA) and empowering them to apply the same MFA to on-premises authentication flows — and those who wish can have multiple identity providers. If Falcon Identity Threat Protection identifies a compromised identity, it can prevent that identity from authenticating and accessing other resources both on-premises or in the cloud. For the remainder of this blog, we focus on Falcon Identity Threat Protection, which has proven to be so effective at stopping breaches and preventing lateral movement that in the recent Round 4 of the MITRE Engenuity ATT&CK® Enterprise Evaluation, CrowdStrike was asked to disable our identity protection capabilities so that MITRE could continue testing the other modules of the CrowdStrike Falcon® platform. This blog shows how Falcon Identity Threat Protection can help federal government agencies fulfill cybersecurity requirements set forth in the cybersecurity EO and how it can help with your Zero Trust journey, including for both on-premises and cloud use cases.

The White House Executive Order and Zero Trust Security

The White House issued the cybersecurity EO in the wake of high-profile cyber incidents including the SUNBURST supply-chain and Colonial Pipeline (DarkSide) ransomware attacks. The EO outlines a number of steps intended to strengthen cybersecurity posture at a national level, including:

- Modernizing federal government cybersecurity

- Enhancing software supply chain security

- Improving detection of cybersecurity vulnerabilities and incidents on federal government networks

- Improving the federal government’s investigative and remediation capabilities

In addition to mandating that federal agencies implement endpoint detection and response (EDR), the EO requires that Zero Trust security principles be followed — something that was emphasized especially due to federal departments and agencies’ continued push to adopt cloud technologies.

It can be nearly impossible to apply Zero Trust principles across on-premises Active Directory and cloud environments, across multiple identity providers. Consider some of the questions that CrowdStrike had to address in architecting Falcon Identity Threat Protection:

- If users can authenticate against Azure AD, Okta, Ping or on-premises Active Directory, how do our customers secure all of those authentication points?

- How do our customers provide the same level of security for on-premises authentication (e.g., Kerberos, NTLM) as they do for cloud authentication that can enforce MFA? This includes service accounts, which are often ignored.

- How do we apply MFA on things, such as remote PowerShell, that leverage non-interactive logon — and why is that such a big deal?

- How do our customers ensure that, if they detect suspicious activity in one of those authorization points or see the identity be compromised, all of the other identity providers are made aware and modify how they treat that respective account?

- How do our customers segment highly privileged accounts so they can only be exposed to not just specific machines, but to machines that are assessed continuously for device hygiene?

Left unaddressed, these scenarios can cause blind spots that can lead to the activity seen in the SUNBURST attack, where the attacker predominantly compromised on-premises credentials, in many cases bypassing MFA to take over entire cloud infrastructures — and leading to devastating consequences. We will explore each of these questions in subsequent blogs and explain how they are addressed by Falcon Identity Threat Protection. But first, let’s view the bigger picture in this blog.

The U.S. Department of Defense’s Seven Pillars of Zero Trust

Following the issuance of the EO, the federal government has been actively developing reference architectures to guide implementation of its mandates. For example, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) released SP 800-207, which discusses various Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA) policy enforcement and policy decision points and has effectively become the foundation for other reference architectures. In addition, the National Security Agency (NSA) released a Zero Trust Maturity Model to help identify the various maturity levels of implementing Zero Trust.

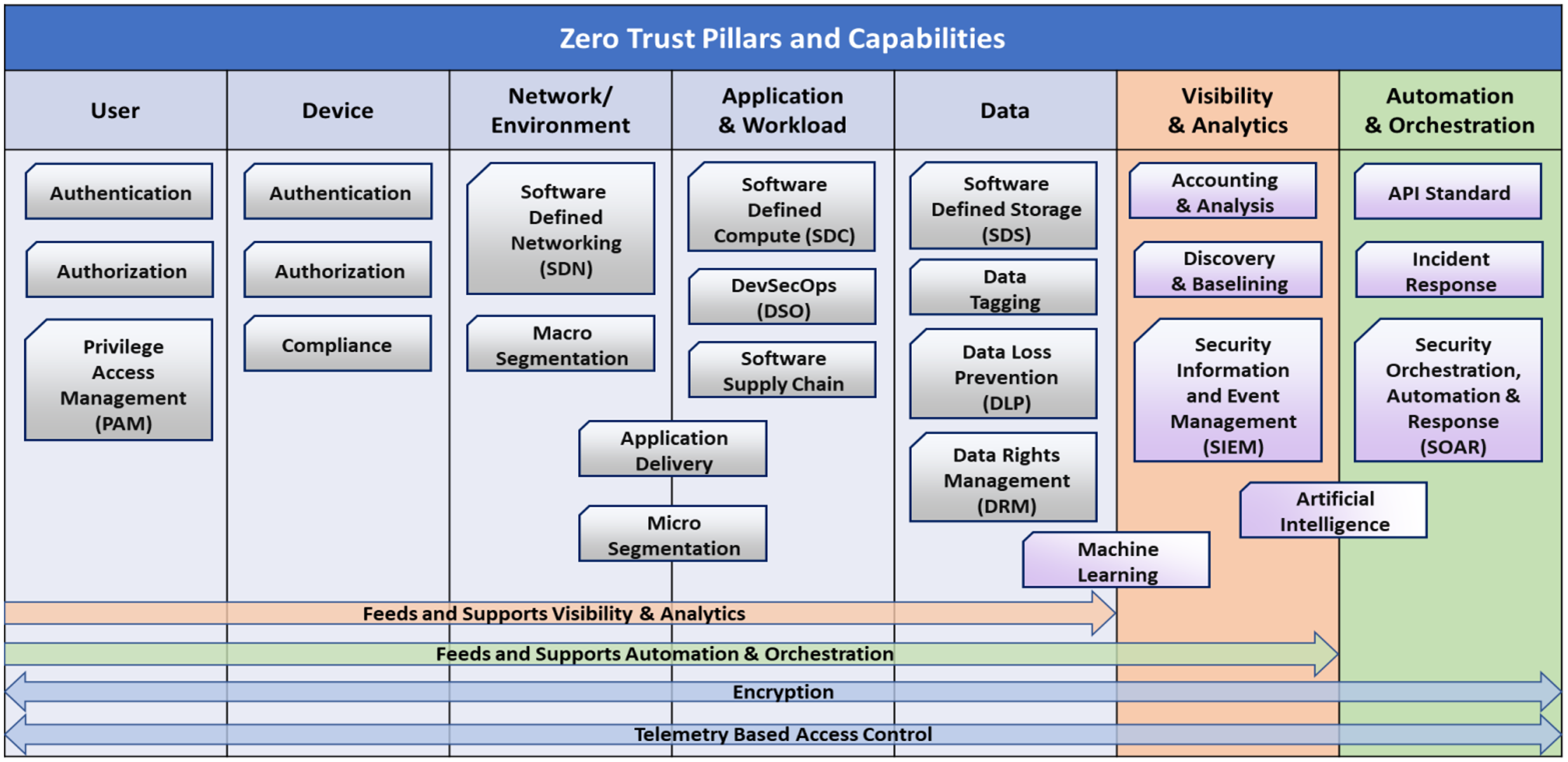

The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) released its Zero Trust reference architecture, which differs from the NIST and NSA architectures in that it discusses common Zero Trust use cases across seven “pillars”: User; Device; Network/Environment; Application and Workload; Data; Visibility and Analytics; and Automation and Orchestration (see Figure 1). We will examine how identity protection plays a role in each pillar of this particular architecture.

It is commonly believed that identity affects only one of the pillars described in this architecture, that of the user. In reality, identity applies to all seven pillars as follows:

- User. Each user has an identity, which typically exists in multiple places (e.g., on devices, in Active Directory, in the cloud). It’s important to remember that a user can normally authenticate at multiple places, whether on premises or to cloud services or another identity provider.

- Device. Devices not only have their own identities, but they are exposed to the identities and other credentials of users that access them. As a result, if a device is compromised, the credentials on that device are also exposed as long as the adversary has access to it.

- Network/Environment. Network devices typically are accessible by service accounts having appropriate privileges. If service accounts are ignored in a defense posture — similar to what happened in the SUNBURST attack — blind spots are created that could lead to significant breaches.

- Application and Workload. Applications and workloads depend on users being authenticated to give them respective privileges — and with the continuous integration/continuous development (CI/CD) that modern applications have today to enable DevOps and DevSecOps practices, if an identity token is compromised that has privileges to push code to a CI/CD pipeline, it could be possible for an adversary to make production-level changes.

- Data. To be fully protected, data must be more than cataloged and tagged appropriately. Users must be able to authenticate appropriately for authorized access to such data. Not only that, data protection can also include only enabling certain applications to access that data, and when implemented, should be executed at the process level. And for processes to be trusted, the operating system and device itself must also be trusted to some degree.

- Visibility and Analytics. Visibility and analytics are used to assess identity across all of these pillars, looking for anomalous activity. In addition, users who wish to access this data also must be able to authenticate at some level, thus requiring identity protection for data access at this layer.

- Automation and Orchestration. Automation and orchestration helps defenders use, proactively if possible, the learned visibility and analytics via API webhooks — API webhooks which require authentication tokens, mapped to an identity, giving it the right permissions to execute. A compromise against one of those tokens can have a devastating impact in an environment.

Through the lens of the DoD’s Seven Pillars of Zero Trust, let’s consider two scenarios that include multiple decision and enforcement points and how and where Falcon Identity Threat Protection fits in. The first shows user authentication against an on-premises resource, leveraging “legacy” authentication protocols, while the second focuses on authentication against a cloud resource, or at minimum a resource behind a cloud-based identity provider. (We will dive deeper into some of these concepts in subsequent blogs, showing, for example, how CrowdStrike secures “legacy” authentication protocols.)

Zero Trust for an On-Premises Resource

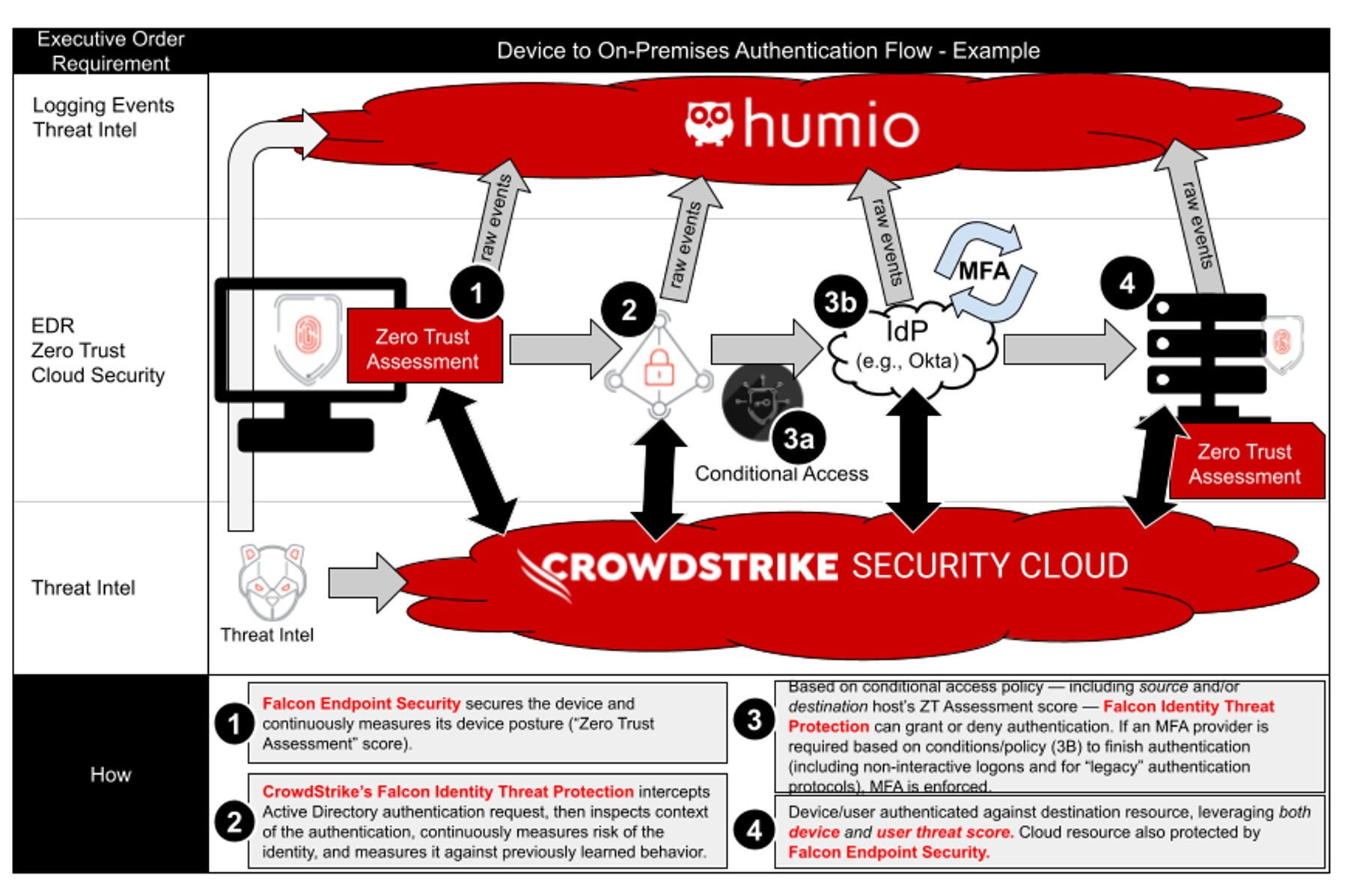

Figure 2 depicts a user-access flow of a device accessing an on-premises resource, using CrowdStrike technology.

Figure 2. Falcon Identity Threat Protection helps continuously monitor and secure identity, including for legacy authentication protocols such as NTLM and Kerberos, without ever touching the application (Click to enlarge)

Figure 2. Falcon Identity Threat Protection helps continuously monitor and secure identity, including for legacy authentication protocols such as NTLM and Kerberos, without ever touching the application (Click to enlarge)In the example shown in Figure 2, the Falcon platform’s endpoint protection helps create a device hygiene score called the “Zero Trust Assessment” score. When a user from a protected device attempts to authenticate or access another system, that authentication continues to occur against on-premises Active Directory as usual. However, Falcon Identity Threat Protection can detect against discrete attacks (e.g., Pass-the-Hash, Overpass-the-Hash, Forged PAC, Golden Ticket) and also measure against the learned baseline of that credential’s normal activity while also assigning a risk score to the credential. That risk score can potentially modify how the credential can successfully authenticate and potentially enforce MFA — all before the user is allowed to authenticate.

Just with the device hygiene score and user-risk score, Falcon Identity Threat Protection solves two of the biggest problems with MFA: It usually has no context of the device itself, and MFA usually isn’t possible for on-premises authentication and certainly is never possible with non-interactive logons (e.g., remote PowerShell, Windows Management Instrumentation).

Zero Trust for the Cloud

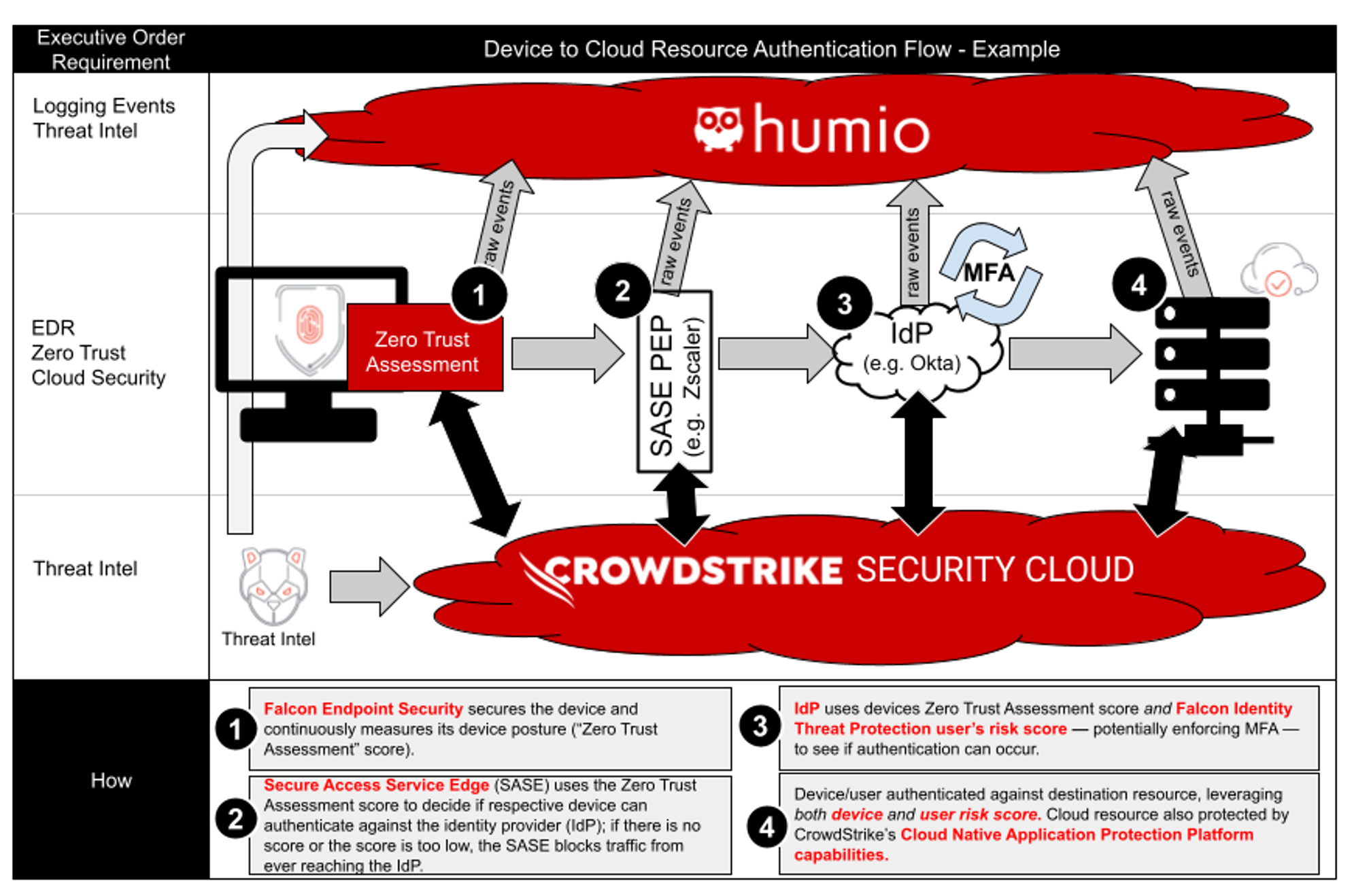

Figure 3 depicts a user-access flow example, this time with a device gaining access to a cloud resource.

Figure 3. CrowdStrike Falcon®’s endpoint protection helps secure and measure the device. The device hygiene is shared across vendors, including the SASE vendor and the identity provider — in this case, Okta. If this was targeting an on-premises resource, CrowdStrike Falcon® Identity Threat Protection can also tailor the workflow for on-premises, at authentication time. (Click to enlarge)

Figure 3. CrowdStrike Falcon®’s endpoint protection helps secure and measure the device. The device hygiene is shared across vendors, including the SASE vendor and the identity provider — in this case, Okta. If this was targeting an on-premises resource, CrowdStrike Falcon® Identity Threat Protection can also tailor the workflow for on-premises, at authentication time. (Click to enlarge)Very similar to the authentication flow of on-premises resources, the authentication flow to a cloud resource provides the ability to have context of the device and the user’s risk score throughout multiple parts of the architecture. The SASE vendor can use the Zero Trust Assessment score from CrowdStrike to see if the device is managed and if it has the right level of trust. It can then pass the authentication flow to the identity provider, in this case Okta, which can also leverage the Zero Trust Assessment score for its decision making. However, the identity provider can also integrate with Falcon Identity Threat Protection in cases where risky on-premises users can result in different behavior or policy in the cloud; for example, perhaps you want users who are acting anonymously to be forced to use MFA when they attempt to access a cloud resource. Falcon Identity Threat Protection can do that, integrating with Microsoft Active Directory, Microsoft Active Directory Federation Services (AD FS), Okta, PingFederate and many other identity services. This solves one of the biggest challenges of securing the cloud: The cloud identity provider is traditionally open to the internet. By placing a SASE in front of the identity provider, and by ensuring the SASE vendor is made aware of the source computer’s device hygiene, we can drastically lower the exposure of our identity provider — no more external brute force attacks. Falcon Identity Threat Protection also solves the big issue of identity providers in the cloud possibly having no idea what is happening on premises. Do we have evidence that the user was compromised on premises, and therefore we should disable authentication or force MFA when they next attempt to access a resource? Thanks to Falcon Identity Threat Protection’s integration with cloud identity providers, this is no longer an issue. In addition, user activity can be seen across multiple identity planes, such as Azure Active Directory (Azure AD). This helps secure the account and enables the execution of a timely incident response investigation.

Conclusion

Thanks to Falcon Identity Threat Protection being available in GovCloud-1, this is available to our federal customers and Defense Industrial Base (DIB) customers. Sharing context across multiple parts of the Computer Network Defense (CND) is important to enable many of these use cases. Gone are the days when we assumed we had limited visibility of our own on-premises identity planes. Gone are the days when we didn’t fuse users' activity across multiple identity providers where that user exists. Through Falcon Identity Threat Protection we can detect identity-based attacks, measure their respective risk score, and measure all-up identity hygiene, while being aware of other factors in our decision logic such as source and destination of the device and so forth. In the following weeks, more blogs will drill into a lot of this content, doubling down on why it's important from a risk and threat perspective.

Additional Resources

- Read the press release.

- Learn more about CrowdStrike Falcon® Identity Threat Protection.

- Discover CrowdStrike solutions for the public sector.

- Read about how CrowdStrike secures significant Impact Level 4 (IL-4) authorization to protect critical U.S. Department of Defense assets.

- Find out how CrowdStrike solutions map to the White House Executive Order.

- Get a full-featured free trial of CrowdStrike Falcon® Prevent™ and learn how true next-gen AV performs against today’s most sophisticated threats.

![Helping Non-Security Stakeholders Understand ATT&CK in 10 Minutes or Less [VIDEO]](https://assets.crowdstrike.com/is/image/crowdstrikeinc/video-ATTCK2-1)

![Qatar’s Commercial Bank Chooses CrowdStrike Falcon®: A Partnership Based on Trust [VIDEO]](https://assets.crowdstrike.com/is/image/crowdstrikeinc/Edward-Gonam-Qatar-Blog2-1)

![Endpoint Protection and Threat Intelligence: The Way Forward [VIDEO]](https://assets.crowdstrike.com/is/image/crowdstrikeinc/GK-Blog_Images-1)