The most prominent eCrime trend observed so far in 2020 is big game hunting (BGH) actors stealing and leaking victim data in order to force ransom payments and, in some cases, demand two ransoms. Data extortion is not a new tactic for criminal adversaries; however, when BGH operations don't result in payment, victims now face a double-headed threat of ensuring their data does not make it into the hands of others.

This first part of a two-part blog series explores the origins of ransomware, BGH and extortion, and introduces some of the criminal adversaries that are currently dominating this data leak extortion ecosystem.

A Brief History of Ransomware and Big Game Hunting

can in part be traced back to around 2008 with the development of fake antivirus software by cybercriminal organizations. These applications showed phony alerts to victims and required payment to “clean up” malware infections. These criminal enterprises were driven by affiliates (known in Russian-speaking criminal forums as partnerka) that earned a commission for each infection and each fake antivirus purchase. At the time, these criminal organizations were able to leverage high-risk merchant accounts to accept credit cards, making it easy for the average victim to pay for their bogus software. Eventually, credit card companies were able to identify and prevent these types of fraudulent transactions, effectively putting the eCriminals out of business. As fake antivirus software disappeared, a new threat emerged that became the predecessor to modern ransomware. Known as a screen locker, this threat would typically display a message impersonating international law enforcement agencies such as the FBI, Interpol and the U.K.’s Metropolitan Police Service. The message essentially locked a victim out of accessing their desktop, demanding payment as a “fine” for the victim’s “criminal” activity, such as viewing illicit pornography, distributing copyrighted material, etc. Payment was made primarily through Ukash, Paysafe and MoneyPak. There were also screen lockers that claimed to encrypt a victim’s files; however, the vast majority did not perform any encryption. The criminals behind this activity used the same affiliate-driven model as the fake antivirus groups to share profits.

Screen lockers virtually disappeared after the introduction of a ransomware family known as CryptoLocker in 2013. CryptoLocker ransomware was revolutionary in both the number of systems it impacted and its use of strong cryptographic algorithms. The ransomware was developed by the so-called BusinessClub that used the massive Gameover Zeus botnet with over a million infections. The group primarily leveraged their botnet for banking-related fraud. However, they realized that not all infections could be monetized easily, so they decided to develop their own ransomware and deploy it to a subset of their botnet’s infected systems. The ransom demand for victims was relatively small — an amount between $100 and $300 USD — and payable in a variety of digital currencies including cashU, Ukash, Paysafe, MoneyPak, and Bitcoin (BTC). CryptoLocker became extremely successful, and other cybercriminals took notice, leading to an explosion in ransomware malware families that continued to use the same affiliate-based profit-sharing model. The next major trend in ransomware began in 2016 with the introduction of the Samas ransomware by BOSS SPIDER. Unlike prior ransomware families, Samas went specifically after businesses rather than individuals. This group initially gained access to corporate networks using Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) and outdated JBoss instances that were exposed to the internet. Once inside the organization, BOSS SPIDER used tactics similar to many state-sponsored threat actors to move laterally, compromise an organization’s domain controller, and thereafter deploy their ransomware. Not only did Samas impact businesses, but BOSS SPIDER realized that they could demand a significantly large ransom payment. CrowdStrike® Intelligence refers to this operational model as big game hunting, which was quickly adopted by INDRIK SPIDER.

Interestingly, INDRIK SPIDER had primarily focused on banking fraud for more than half a decade. However, after BOSS SPIDER’s success with BGH attacks, INDRIK SPIDER realized that ransomware was far more profitable and far less complex to monetize (e.g., it did not require an extensive money mule network to launder funds). This actor shifted from banking fraud to ransomware in 2017, developing BitPaymer ransomware, and more recently, WastedLocker. Since the early BGH operations of BOSS SPIDER and INDRIK SPIDER, the trend has transformed the eCrime ecosystem. New adversaries have adopted BGH techniques, and enablers have built tools to cater to this burgeoning market.

A New Trend: Cyber Extortion

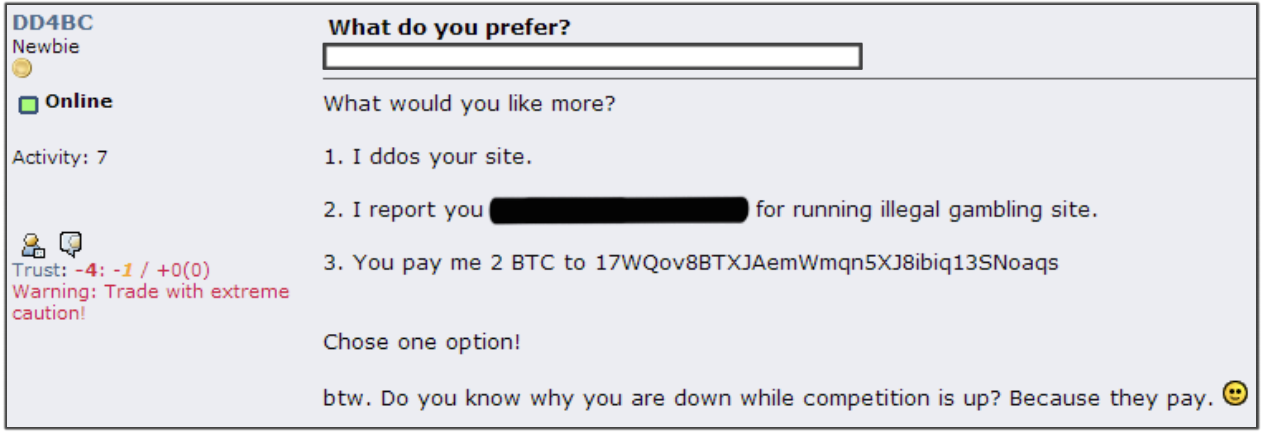

Cyber extortion also has a long history, including email extortion, distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) extortion and data extortion attacks. Email extortion is likely the most prolific and longest-standing form of cyber extortion given its low barrier to entry. In order to operate campaigns, criminal actors merely need to acquire leaked passwords, which can be easily found on Pastebin, or other more superficial victim information, such as a telephone number, to help appear legitimate in that they have somehow acquired damaging information related to the victim. These actors typically send an email to the victim with one piece of legitimate personal information, claim the victim was infected with malware and thus acquire more damaging information. The actor then demands a ransom payment in order to keep the information from being sent to the victim’s friends, family or colleagues. A slightly more sophisticated version of this technique came with the emergence of DDoS extortion. As early as April 2014, PIZZO SPIDER (also known as DD4BC, which is an acronym for “DDoS for Bitcoin”) sent emails claiming that they would DDoS a business and take down their services if the business did not pay the demanded ransom amount, as shown in Figure 1. Later, MIMIC SPIDER and other criminal actors operating Internet of Things (IoT) botnets, such as Mirai, used this technique. Some of these actors conducted DDoS attacks before the threat to prove they could follow through, while other actors simply rode the coattails of other attacks, sending the threat while unable to follow through with the deed.

Figure 1. PIZZO SPIDER threatening to DDoS a gambling site unless ransom is paid (click image to enlarge)

Figure 1. PIZZO SPIDER threatening to DDoS a gambling site unless ransom is paid (click image to enlarge)One of the more publicized actors to capitalize on this trend and take it to the next level is OVERLORD SPIDER, aka The Dark Overlord. Similar to ransomware operators today, OVERLORD SPIDER likely purchased RDP access to compromised servers on underground forums in order to exfiltrate data from corporate networks. The actor was known to attempt to “sell back” the data to the respective victims, threatening to sell the data to interested parties should the victim refuse to pay. There was at least one identified instance of OVERLORD SPIDER successfully selling victim data on an underground market.

Putting It All Together: Cyber Extortion With Ransomware

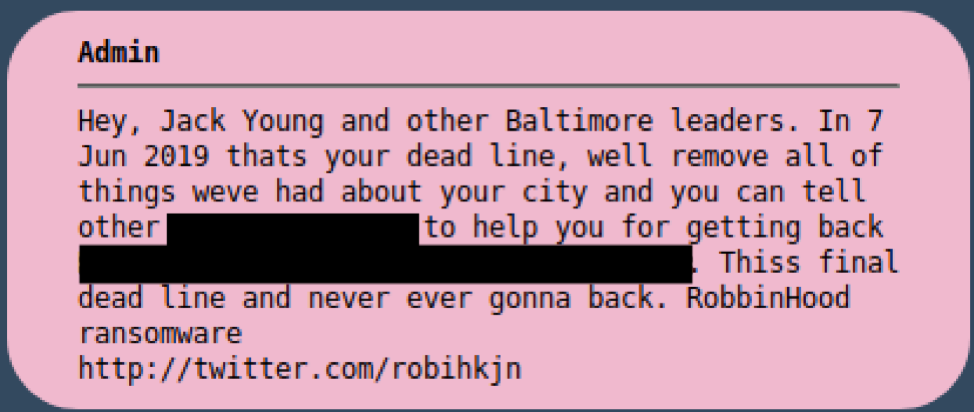

On May 7, 2019, Mayor Bernard “Jack” Young confirmed that the network for the U.S. City of Baltimore (CoB) was infected with ransomware, which was announced via Twitter1. This infection was later confirmed to be conducted by OUTLAW SPIDER, which is the actor behind the RobbinHood ransomware. The actor demanded to be paid 3 BTC (approximately $17,600 USD at the time) per infected system, or 13 BTC (approximately $76,500 USD at the time) for all infected systems to recover the city’s files. On May 9, 2019, CrowdStrike Intelligence observed OUTLAW SPIDER post an image on the Tor hidden service hosted by the actors to establish communications with their victims (known as a payment portal). This image contained sensitive information allegedly taken from the CoB network and was posted along with a message stating, “The city also said no personal data has been compromised, Really ?!.” This comment was likely in response to public statements by the city that no personal information had been compromised during the incident and to incentivize ransom payment. Young later stated that not only was the city not going to pay the ransom, but that “we’re going to get and punish them to the fullest extent of the law.”2 This was followed by further communications from OUTLAW SPIDER, through an established Twitter account and the payment portal, stating they would remove all collected city information if the ransom was paid by a specified deadline, as shown in Figure 2.

Although ineffective, the incident with the CoB and OUTLAW SPIDER was the first instance observed by CrowdStrike Intelligence of data extortion to incentivize ransom payment.

Ransomware Actors Leaking Victim Data

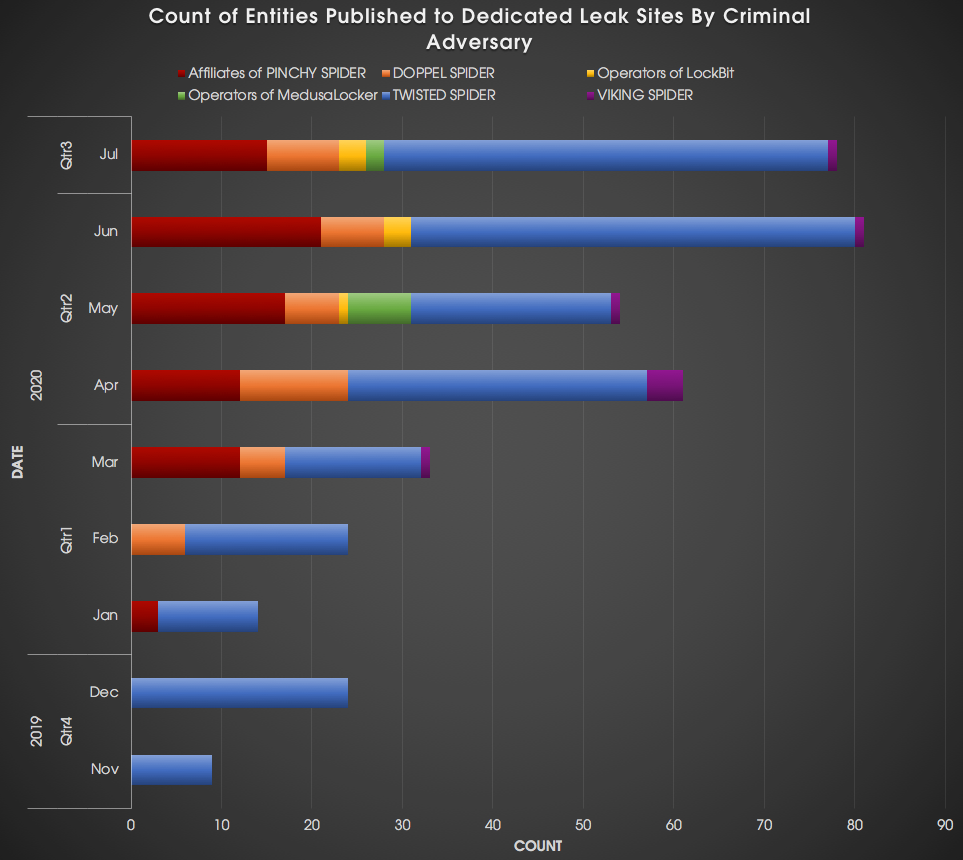

After the CoB incident with OUTLAW SPIDER, several months passed before TWISTED SPIDER reintroduced this technique in November 2019. TWISTED SPIDER’s late 2019 activity proved the catalyst for numerous eCrime threat actors adopting the use of dedicated leak sites (DLSs) to threaten the distribution of company data in various forms. TWISTED SPIDER remains the most prolific actor using this technique, with a variety of actors adopting this technique through the first half of 2020, as shown in Figure 3. This section provides an overview of each of these threat actors and how they incentivize and pressure victims to pay ransoms.

Figure 3. Number of entities published to dedicated leak sites by criminal adversaries from November 2019 through July 2020 (click image to enlarge)

Figure 3. Number of entities published to dedicated leak sites by criminal adversaries from November 2019 through July 2020 (click image to enlarge)TWISTED SPIDER

TWISTED SPIDER has been operating Maze ransomware since at least May 2019; however, the actors did not start leaking victim data until November 2019. They first advertised their data leaks on a Russian underground forum, claiming to include 10% of the victim’s data and threatening to leak the remaining data in a later post. In these posts, the criminal actor called out popular security companies and warned another victim to pay the ransom quickly. On December 10, 2019, they created a DLS but continued to post to Russian underground forums. On January 2, 2020, a victim filed a lawsuit against TWISTED SPIDER and the company hosting the DLS containing the stolen files. This caused the site to be temporarily taken down, but TWISTED SPIDER merely created a new DLS on January 9, 2020. Despite the legal action, the actor remained active, continuing to deploy their ransomware on victim networks and posting data either on underground forums or to the new DLS. Currently, the criminal actor hosts the DLS simultaneously on the web and on a Tor hidden service. TWISTED SPIDER’s audacious commentary continues to persist as they mock security companies and researchers in posts on their DLS, and call out victims before and after the release of data to induce payment. When TWISTED SPIDER leaks victim data, the actor publishes identifying information, including the victim’s headquarters, phone number, fax number and website, as shown in Figure 4. If the post is intended to serve as a warning, the actors will only upload a sample of data for proof. In addition to leaking data on their DLS, TWISTED SPIDER also uses the site as a platform for their press releases. These releases include terms and conditions for their operations, naming and shaming victims, and proclamations of the group’s alleged motivations and goals.

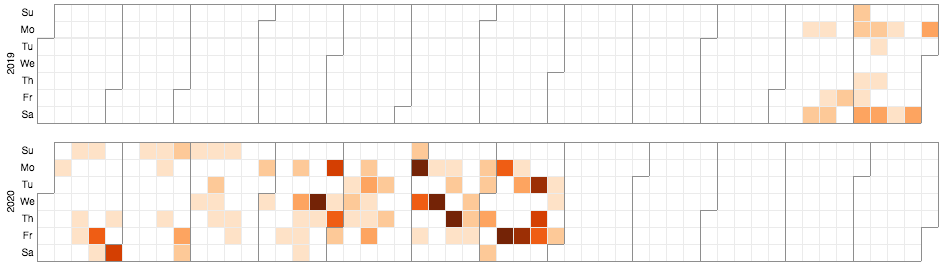

While TWISTED SPIDER may not have been the first ransomware actor to conduct data extortion, they have been successful in operationalizing the practice. The actor has continued to leak data with increased frequency and consistency. The timeline in Figure 5 provides a view of data leaks from over 230 victims from November 11, 2019, until May 2020. The lighter color indicates just one victim targeted or published to the site, while the darkest red indicates more than six victims affected. TWISTED SPIDER has had multiple instances where they have published over 10 victims in one day. In addition, the group appears to work most days of the week, with Sunday being the least prolific day and Mondays and Fridays being the most active.

Figure 5. Timeline of victims published to TWISTED SPIDER’s news site by publish date, or actor-claimed lock date when available, through July 2020 (click image to enlarge)

Figure 5. Timeline of victims published to TWISTED SPIDER’s news site by publish date, or actor-claimed lock date when available, through July 2020 (click image to enlarge)PINCHY SPIDER

On December 9, 2019 (approximately two and a half weeks after TWISTED SPIDER’s first leak), a vendor of PINCHY SPIDER’s REvil ransomware as a service (RaaS) posted a threat to leak victim data to an underground forum. This is the first time CrowdStrike Intelligence observed the group or their affiliates making such a threat, and it appeared to be in frustration over failing to monetize compromises at a U.S.-based managed service provider (MSP) and a China-based asset management firm. Since that time, affiliates of PINCHY SPIDER have posted data on more than 80 victims.

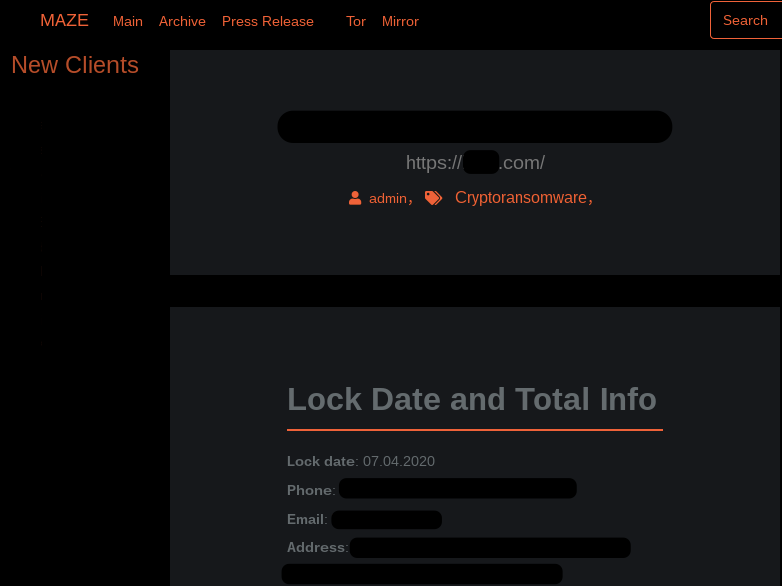

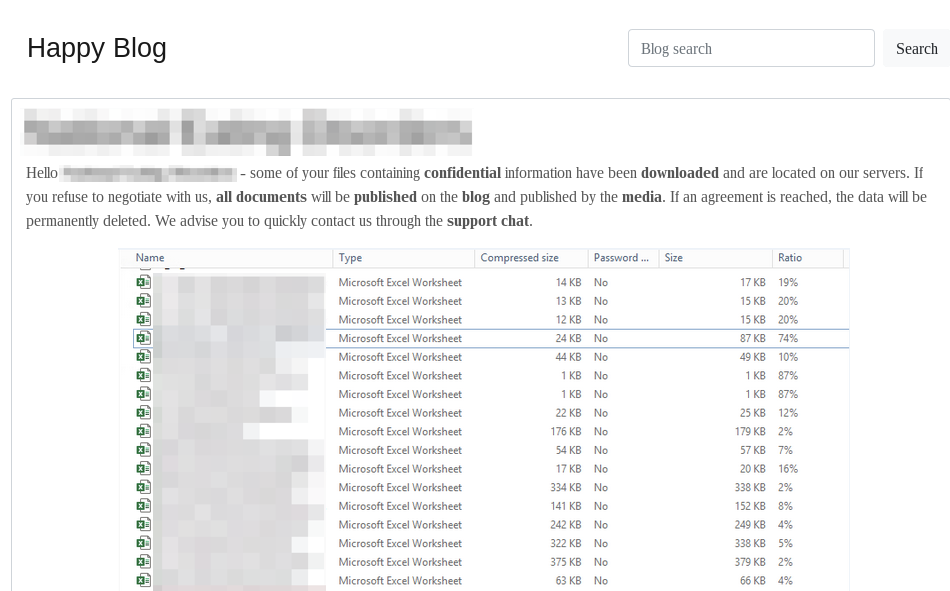

PINCHY SPIDER began leaking victim data on underground forums before launching a DLS on February 26, 2020, hosted using a Tor hidden service. Similar to TWISTED SPIDER’s initial leaks, PINCHY SPIDER warns victims of the planned data leak, usually via a blog post on their DLS containing sample data as proof (see Figure 6), before releasing the bulk of the data after a given amount of time. REvil will also provide a link to the blog post within the ransom note distributed to systems encrypted by REvil ransomware. The link contains a GET parameter, which if provided with a given link, will display the leak to the affected victim prior to being exposed to the public. Upon visiting the link, a countdown timer will begin, which will cause the leak to be published once the given amount of time has elapsed.

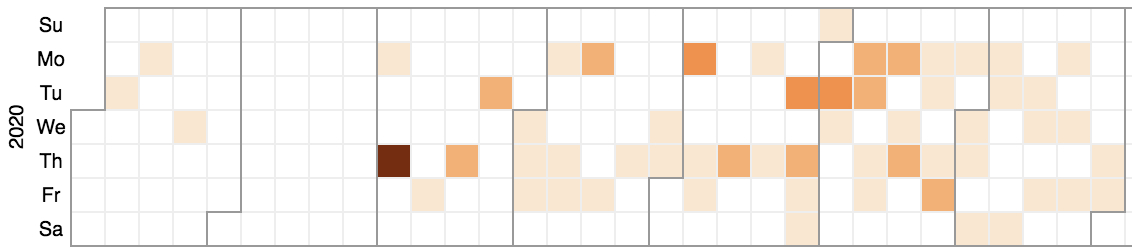

A timeline for victims affected by PINCHY SPIDER’s data leaks is shown in Figure 7. A single victim published is displayed as the lightest color; the darkest color indicates six victims were published to the site in one day. While PINCHY SPIDER affiliates took time to begin using the tactic, by the time April 2020 rolled around, the publishing of victim data became more consistent. In addition, unlike TWISTED SPIDER, affiliates of PINCHY SPIDER appear to take weekends off; victim data is typically published during the working days of Monday through Friday.

Figure 7. Timeline of victims affected by data leaks conducted by affiliates of PINCHY SPIDER from January through July 2020 (click image to enlarge)

Figure 7. Timeline of victims affected by data leaks conducted by affiliates of PINCHY SPIDER from January through July 2020 (click image to enlarge)DOPPEL SPIDER

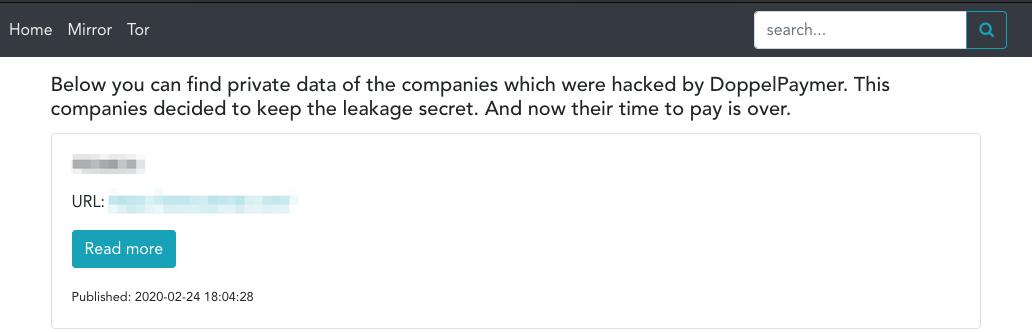

DOPPEL SPIDER, operator and developer of the ransomware DoppelPaymer, was next to leak victim data.

Since introducing their DLS (see Figure 8) on February 21, 2020, the actor has published data from over 40 victims. However, while TWISTED SPIDER and PINCHY SPIDER typically leak data in at most three parts, DOPPEL SPIDER will leak data over multiple days, and sometimes weeks. Additionally, DOPPEL SPIDER will only post victim information after a victim refuses to pay and the timer for the payment deadline has expired. The actor is likely allowing the victim to observe that the data is legitimate and incentivize them to pay the ransom before all of their data is leaked.

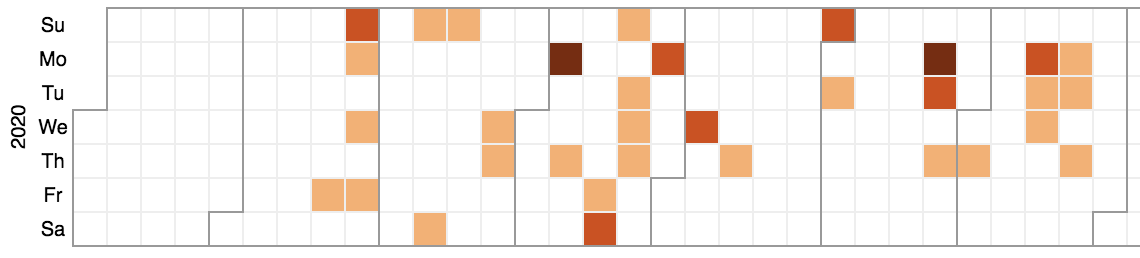

As can be seen in Figure 9, DOPPEL SPIDER is not as visibly prolific as TWISTED SPIDER or PINCHY SPIDER and leaks data sporadically, occasionally going one to two weeks without victims being published. The timeline below displays a single victim published to the site as the lightest color with up to three victims, the darkest color, having been published in a given day.

Figure 9. Timeline of data leaks conducted by DOPPEL SPIDER, February through July 2020 (click image to enlarge)

Figure 9. Timeline of data leaks conducted by DOPPEL SPIDER, February through July 2020 (click image to enlarge)VIKING SPIDER

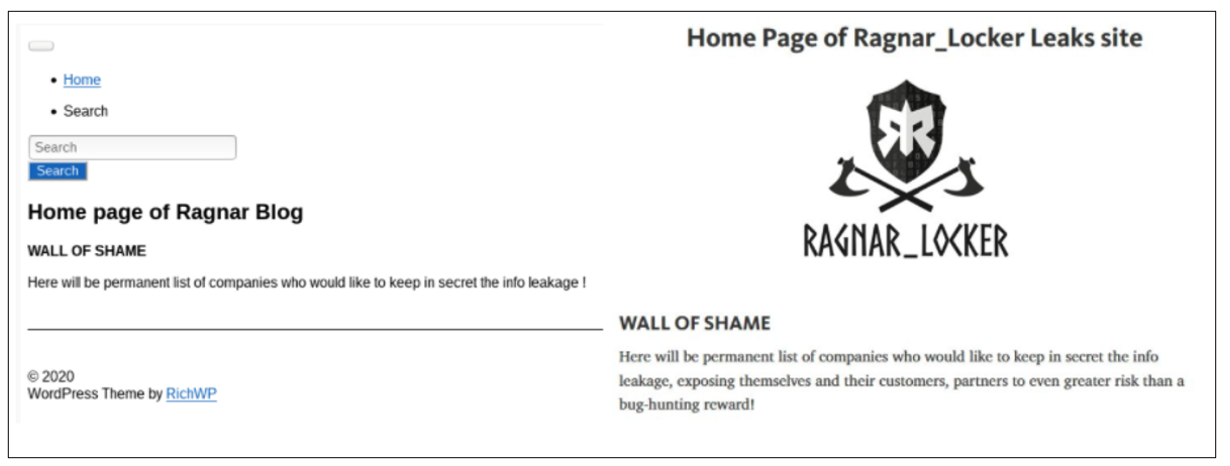

VIKING SPIDER is the criminal group behind the development and distribution of Ragnar Locker ransomware. While public reporting indicates the group began threatening to leak victim data in February 2020, a DLS was not observed until April 2020. The DLS is hosted on Tor, and similar to other actors, proof of data exfiltration is provided before the stolen data is fully leaked. Since this time, at least 12 victims have been observed on their DLS, which is shown in Figure 10.

LockBit

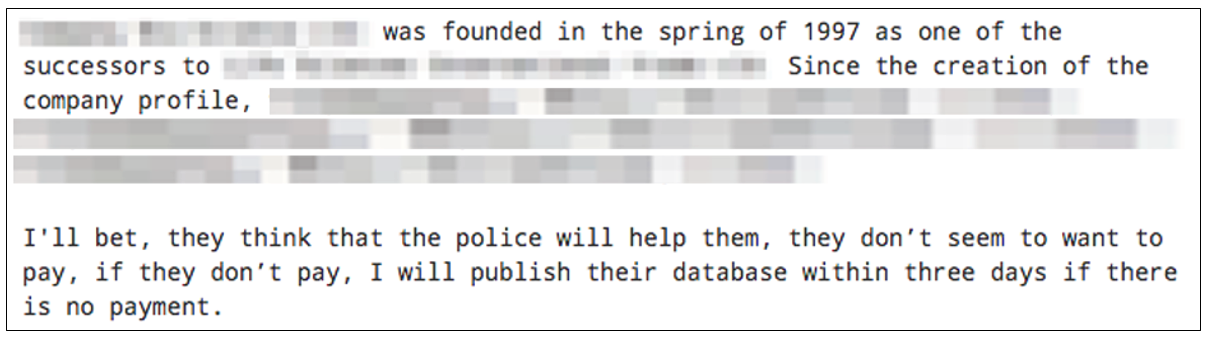

In development since at least September 2019, LockBit is available as a RaaS, advertised to Russian-speaking users or English speakers with a Russian-speaking guarantor. In May 2020, an affiliate operating LockBit posted a threat to leak data on a popular Russian-language criminal forum, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Example content of forum post threatening data leak by affiliate operating LockBit (click image to enlarge)

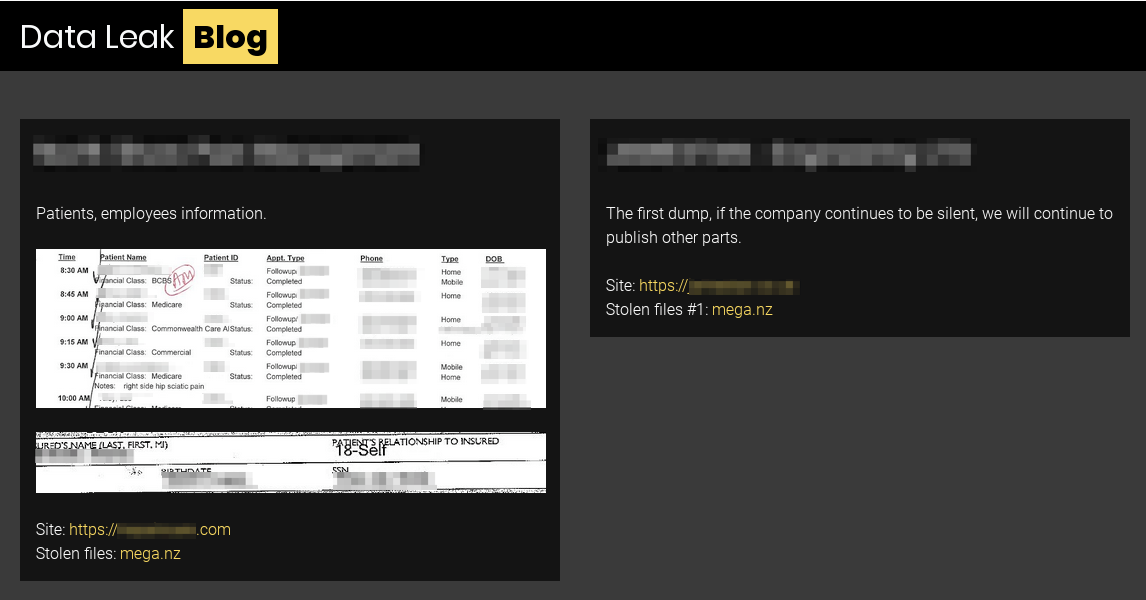

Figure 11. Example content of forum post threatening data leak by affiliate operating LockBit (click image to enlarge)In addition to the threat, the affiliate provides proof, such as an image of the folder structure and at least one screenshot of an example document contained within the victim data. Once the deadline passes, the affiliate is known to post a mega<.>nz link to download the stolen victim data. This affiliate has threatened to publish data from at least nine victims. Currently, there is no DLS in operation dedicated to LockBit ransomware.

MedusaLocker

MedusaLocker is a ransomware family that was first seen in the wild in early October 2019. In January 2020, a fork of MedusaLocker named Ako was observed, which has been updated to support the use of a Tor hidden service to facilitate a RaaS model. Operators of the Ako version of the malware have since implemented a DLS (Figure 12). At least nine victims have been published to the site since its inception.

Conclusion

Data extortion is not a new trend, but it seems to be growing in popularity to fuel ransomware operations. OVERLORD SPIDER is one of possibly many eCrime actors using data theft and extortion as the main driver for their operations — in fact, it is the only method used by this actor. OVERLORD SPIDER’s operations have been well publicized and may have influenced other actors about the potential effectiveness of this tactic in eliciting payment.

To date, the majority of ransomware operators engaged in BGH operations have adopted or threatened the data-theft-and-leak tactic, with the exception of INDRIK SPIDER and WIZARD SPIDER. It is also likely that less sophisticated ransomware operators will threaten data leaks, even if they do not have the capability to exfiltrate data, in order to capitalize on the current trend of data extortion by bluffing.

As organizations improve their capabilities to rebound from ransomware attacks and security researchers continue to create decryptors for ransomware, there is less incentive for victims to pay the ransom in order to reclaim files. However, criminal actors have found a way to thwart these defensive measures. By exfiltrating data from victim networks and leaking it if companies refuse to comply, criminal actors might be able revitalize the financial returns of their criminal activities. This blog was written by CrowdStrike Intelligence analysts Molly Lane, Josh Reynolds, Brett Stone-Gross and Bex Hartley. 1 https://twitter<.>com/mayorbcyoung/status/1125826676280188929 2 https://www.baltimore<.>com/politics/bs-md-young-hack-20190510-story.html

Additional Resources

- Download: CrowdStrike 2020 Global Threat Report.

- To learn more about how to incorporate intelligence on threat actors into your security strategy, visit the CrowdStrike Falcon® Intelligence Threat Intelligence page.

- Learn more about the powerful, cloud-native CrowdStrike Falcon®®platform by visiting the product webpage.

- Get a full-featured free trial of CrowdStrike Falcon® Prevent™ and learn how true next-gen AV performs against today’s most sophisticated threats.

![Helping Non-Security Stakeholders Understand ATT&CK in 10 Minutes or Less [VIDEO]](https://assets.crowdstrike.com/is/image/crowdstrikeinc/video-ATTCK2-1)

![Qatar’s Commercial Bank Chooses CrowdStrike Falcon®: A Partnership Based on Trust [VIDEO]](https://assets.crowdstrike.com/is/image/crowdstrikeinc/Edward-Gonam-Qatar-Blog2-1)